cultură şi spiritualitate

Vocal

https://www.gramophone.co.uk/features/article/the-50-greatest-js-ba...

Sacred Cantatas

Bach Collegium Japan / Masaaki Suzuki

(BIS)

While John Eliot Gardiner performed his near-complete Bach sacred cantata ‘pilgrimage’ in the course of the great millennial year in 50 contrasting locations, Masaaki Suzuki’s 18-year journey has been a gradually unfolding musical voyage (a chronological rather than seasonal progression) and in the singular, luminous hallmark acoustic of the Shoin Women’s University Chapel in Kobe. Comparisons of two exceptional Bach projects are largely rendered odious by the fact that Gardiner’s work largely represents a repository of recorded concerts while Suzuki’s has been a considered, slow-burn studio project. If the early critical rhetoric of Vol 1 (Cantatas Nos 4, 150 and 196 – 6/96) was one of astonishment that a Japanese choir could sing such perfect German or that Japanese instrumentalists could comprehend ‘style’ so effortlessly, it soon became apparent that the world is smaller than we think and that Suzuki’s subtle and embedded understanding of Bach was yielding an important set of new recorded ‘texts’ in a global musical language. No complete series can deliver equal inspiration in every volume but Suzuki and BCJ have created an indelible mark on Bach’s recorded vocal landscape. The best is as good as anyone anywhere – and the whole, of the six complete cantata sets, probably the most consistent. Jonathan Freeman‑Attwood (December 2013)

☆

Sacred Cantatas

Monteverdi Choir; English Baroque Soloists / Sir John Eliot Gardiner

(SDG)

One of the most staggering achievements – in terms of ambition, execution, presentation and cultural significance – emerged from the millennial project by the Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists and Sir John Eliot Gardiner to perform all of Bach’s sacred cantatas during the course of a single year. The performances, which were recorded during the tour, started to emerge on disc in 2005 and the first volume secured Gramophone’s Recording of the Year; the entire project was given a Special Achievement Award in 2011. Now all 56 CDs have been gathered together in an elegant black box. As well as a slim booklet of essays and a complete listing by both CD contents and BWV number, there’s a CDR that contains Gardiner’s excellent notes as well as the texts and translations of all the cantatas. Steve McCurry’s extraordinarily vivid photographs still adorn each sleeve to great effect. But it is the impact of this music that makes it such an achievement: Bach squares up to the highs and lows of mankind, and our baser motives and higher aspirations are engaged with in a musical language that transcends the passing of time. If ever part of a major composer’s work needed rediscovering it’s the Bach cantatas – we really know too few of them. James Jolly (January 2014)

☆

Sacred Cantatas

Vienna Concentus Musicus/ Nikolaus Harnoncourt; Leonhardt Consort / Gustav Leonhardt

(Warner Classics)

In the 19 years since its inception, this cycle of all of Bach 's sacred cantatas in 45 volumes and on 83 discs has enriched the catalogue incalculably. Beside the more glamorous projects that have captured the attention in the sphere of period performance, the work of Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Gustav Leonhardt and their colleagues in Amsterdam and Vienna has progressed steadily and with consummate musicianship. Each volume in this monumental project offers rich rewards and bears witness not only to Bach's unparalleled genius but to the remarkable consistency and imagination of the many performers who have contributed to it over the years. It is a series that was started long before cycles and integrales became the fashion and it stands to outlive many of the cycles that have come and gone during the last two decades. James Jolly (October 1990)

☆

Cantatas Nos 82 and 199

Emma Kirkby sop Katharina Arfken ob Freiburg Baroque Orchestra / Gottfried von der Goltz vn

(Carus)

One of the world’s brightest Baroque ensembles performing with one of the world’s most admired Baroque sopranos sounds an enticing proposition‚ and so it should. What is more‚ the solo cantatas on offer here are two of Bach’s most moving: Ich habe genug‚ that serene contemplation of the afterlife; and Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut‚ a relatively early work with a text which moves from the wallowing selfpity of the sinnner to joyful relief in God’s mercy. Each contains music of great humanity and beauty‚ and each‚ too‚ contains an aria of aching breadth and nobility – the justly celebrated ‘Schlummert ein’ in the case of Ich habe genug‚ and in Mein Herze the humble but assured supplication of ‘Tief gebückt’. This aria alone ought to make the cantata a more familiar one‚ but there is plenty more to recommend it‚ including a griefladen first aria with obbligato oboe‚ a dignified chorale with obbligato cello‚ and recitatives whose expressiveness is enhanced by stoical string accompaniment. Both could have been written for Emma Kirkby‚ who‚ thrillingly virtuosic though she can be‚ is perhaps at her best in this kind of longbreathed‚ melodically sublime music in which sheer beauty of vocal sound counts for so much. Not that technique does not come into it‚ and Kirkby’s allows her to shape vibratoless long notes and phrases with utter security and ravishing vocal quality‚ with only the occasional high note sounding slightly pinched. Above all‚ however‚ her intelligence and unfailing attention to text are a lesson to all; in ‘Schlummert ein’‚ the way her voice subsides almost to nothing‚ retreating into the orchestral texture at ‘fallet sanft’ (fall asleep)‚ is entrancing.

The support of the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra is total‚ combining tightness of ensemble with such flexibility and sensitivity to the job of accompaniment that you really feel they are ‘playing the words’. The obbligato contributions of flautist Karl Kaiser and oboist Katharina Arfken‚ furthermore‚ are outstandingly musical. And if that were not enough‚ the Freiburgers also give one of the most satisfyingly thoroughbred accounts of the Violin and Oboe Concerto that I have heard. Add a recorded sound which perfectly combines bloom‚ clarity and internal balance‚ and you have a CD to treasure. Lindsay Kemp (November 2001)

☆

Mass in B minor

Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists / Sir John Eliot Gardiner

(SDG)

The degree to which conductors are more or less synonymous with particular works is a largely subjective matter, though few would argue that the Mass in B minor captures with special pertinence the flavour of John Eliot Gardiner’s distinctive contribution to music-making over 50 years of professional life. While he has only recorded the work once before, in 1985, performances of the work have peppered his career in all four corners of the globe. That recording was something of a yardstick at a time when the pioneering compact disc coincided with the second birth of the ‘early music movement’ in tsunami mode: Gardiner let rip, in short, with a towering performance of blazing choruses and oratorian solos, firmly planting his feet in the DG space that Karl Richter had vacated with his early death four years earlier.

If that performance now seems uncontained in a bristling vigour of varying durability, the intervening 30 years have transformed Gardiner’s B minor with his consistently impressive Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists from something less culturally reactive and adrenalin-driven towards a more contained, pictorial and inhabited ideal, though no less energised. If there was anything Gardiner learnt from the monumental traversal of the cantatas during that great millennium year, it was to take longer-breathed interpretative positions with Bach and to know when to let the singers, especially, and the music do the work.

From the outset here, Gardiner’s meticulous grasp of the detail and architecture in tandem is almost terrifyingly auspicious. The Kyrie has never felt more naturally contrasting in both that respect and in the etched placement (some might find it a touch too articulated) of the fugal entries; it’s a ‘melos’ – an unbroken evolution of line – which becomes especially evident from the tautly conceived ‘Et in unum’ and the most luscious ‘Et incarnatus’, each underpinned by skilful dynamic contouring.

Indeed, the idea of the Mass as Bach’s ‘summa’ anthology (a work that may never even have been conceived as a single piece) has often inhibited that elusive golden ‘arc’ where the culminating ‘Dona nobis’ feels magnetised to all before it. How can it be uncovered without pressing too hard on the tempi or under-curating those reflections of discrete stillness? If Brüggen’s first reading with its purity of abstraction comes close in its controversially instrument-heavy recording and, more recently, Jonathan Cohen’s elegant and generous account asks further questions – albeit in the difficult acoustic of Tetbury Church – we have a further vision here with Gardiner’s extraordinary, single-minded, quasi-mathematical proof.

It starts with peerless choral singing, the trumpet-led movements bolted into an unerring tactus and purring through the gears; the ‘Et exspecto’ with its luminous lead-in is quite miraculous, as is the shining portal of the Sanctus. Such is Gardiner’s dramatic placement that the predominance of D major never palls. Less consistent are the solo movements. Gardiner’s policy of showcasing young vocal talent inevitably leads to occasional gaucheness and some hints of tiredness, but the price is small: there is much that is winning, and the ‘Laudamus te’ (Hannah Morrison) is one of several examples of fresh tenderness.

Out of this youthful paradigm emerges an especially corporate endeavour, one that challenges pre-conceived ideas on vocal and instrumental ‘role-play’, and celebrates Bach’s endlessly sophisticated relationship between players and singers: perspectives where our modern ears are forced to re‑evaluate expectations within our conventional understanding. This is borne out in many ways, none more than the dialogues of the ‘Quoniam’, where the bass, horn and bassoons fulfil many purposes in a changing canvas.

Gardiner’s admiration for this work is palpable in every bar, perhaps over-curated for some; and if so the softer-hues of Cohen may be preferred. But in the grip of its conceits and its virtuoso executancy, captured in the strikingly immediate recorded sound of LSO St Luke’s, this High Mass joins a distinguished discography at high table. Jonathan Freeman-Attwood (December 2015)

☆

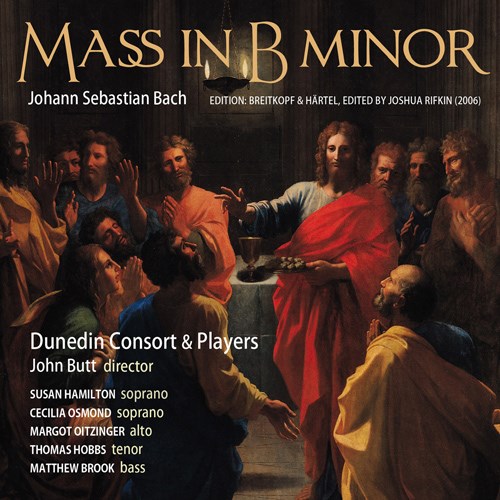

Mass in B minor

Dunedin Consort and Players / John Butt

(Linn)

There are few who strive sincerely to juxtapose the bedfellows of academic rigour and inspired musicianship. Given his recent Handelian activity at the helm of the Dunedin Consort and Players, some might have forgotten that John Butt is a Bach research specialist and author of the Cambridge Handbook on the Mass in B minor. In the booklet he explains his thoughts about historically informed performance practice (one voice per part, following the evidence outlined in the writings of Joshua Rifkin and Andrew Parrott), and discusses his choice to make the first recording of Rifkin’s recent edition (which reconstructs Bach’s score c1749, without later accretions). Butt’s interpretation owes firm allegiance to the “OVPP” creed that will not please everyone (even if detractors have not yet produced a single scrap of proof to refute it), but the Dunedin Consort and Players are never perfunctory or merely dogmatic. This performance demands to be heard.

Butt has considered every musical connection, context, texture and form. Not only do the individual movements feel spot-on in articulation and affekt but the free-flowing pacing from one section to the next makes it easy for the listener to be pulled along. Each section of the Roman Ordinary is envisaged as continuous music, so there are no pregnant pauses between solo and choral movements. The first chords of the “Kyrie” are sung boldly by the 10 singers (five “principals” and another five “ripienists”), and the solemn fugue is performed with gentle ardency; every gesture, detail, suspension and arching line is judged and executed with transparency, flexibility and rhetorical potency.

Thomas Hobbs and Matthew Brook sing the principal lower-voice contrapuntal passages with sensitive blend and superb intonation: they also declaim their solo movements with confidence and eloquence. The higher-voiced principals are marginally less successful: the combination of Susan Hamilton and Cecilia Osmond in the duet “Christe eleison” occasionally threatens fragility but perhaps more authoritative and smoother-toned soprano soloists would have been less adaptable in the choruses. Butt’s flowing tempo for “Agnus Dei” prevents Margot Oitzinger from conveying the breathtaking timelessness some might hanker after but catharsis is tangible in “Benedictus” (performed movingly by Hobbs and flautist Katy Bircher). The galant character adopted by Butt’s elegant harpsichord continuo, Patrick Beaugiraud’s poignant oboe and tasteful strings during “Qui sedes” proceeds without pause into “Quoniam”; Anneke Scott’s sparky horn playing and Matthew Brook’s conversational authority conspire to take no prisoners, and the momentum carries through into a knock-out “Cum Sancto Spiritu”.

Once upon a time the bravery of minimal forces tackling this repertoire was ridiculed by sniffy sceptics. Butt and the Dunedins might not change any entrenched minds; but the climax of “Gratias agimus tibi” is as bold, resonant and glorious as anything one would expect (and not always get) from larger forces. The opening of the “Gloria” bursts forth with radiant splendour but also has a dance-like lilt, and with Bach’s intricate writing emerges as a compelling dialogue.

The Dunedin Consort’s singing conveys the ebb, flow and shading of Bach’s choruses with ease and naturalness. The sonorities of full homophonic chords concluding the grandest choruses are thrilling, whereas the densely polyphonic choral passages always possess clarity and logic thanks to the disciplined interplay of the singers. The five principals combine to rapturous effect in “Et incarnatus est”, and Butt’s handling of the strings and flutes during “Crucifixus” is both patient and emotionally charged.

Many excellent recordings of this monumental work cater for different tastes and priorities. Some have more consistent line-ups of soloists, equally impressive choirs (of varying sizes) and comparably strong artistic direction. Although an excellent one-voice-per-part version is nothing new, Butt’s insightful direction and scholarship, integrated with the Dunedin’s extremely accomplished instrumental playing and consort singing, amount to an enthralling and revelatory collective interpretation of the Mass in B minor – perhaps the most probing since Andrew Parrott’s explosive 1985 version (Virgin, 8/86). David Vickers (August 2010)

☆

Magnificat

Ricercar Consort / Philippe Pierlot

(Mirare)

Presented as a grand work with a single-voice chorus, this reading of the Magnificat is as vitally conceived and multi-dimensional as I can recall. So often the blend of a madrigal-sized choir detracts from a necessary corporate impact but such is the keen characterisation of the text and the willingness to “come and go” in the texture that the Ricercar Consort convey, in the exultant framing movements and “Omnes generationes”, a rare combination of visceral rhythmic verve and vocal energy.

The solo movements are also bursting with personality, soprano Anna Zander delivering a robustly fluent “Et exultavit” and her counterpart, Maria Keohane, a sensually captivating “Quia respexit”, whose oboe d’amore obbligato dovetails her lines with imploring beauty. If the alto, Carlos Mena, is the least vocally poised, then his “Esurientes” is still exceptionally judged and his duetting with tenor Hans-Jörg Mammel in “Et misericordia” sensitively projected. As throughout, all the singing is complemented by delectable instrumental accompaniments. “Suscepit Israel” is the highlight, however: a bittersweet Carissimi-like trio (perhaps more Scarlatti Stabat mater in supplication?) of mesmerising fragility.

The G minor Mass represents a clever juxtaposition of conceits with the Magnificat, as Bach revisits choice cantata movements (from BWV72, 102 and 187) and parodies them so successfully – whatever past curmudgeons say – that this lesser-known example from the four so-called “Lutheran Masses” reminds us what they can communicate so specially with such a finely blended and integrated ensemble as the Ricercar Ensemble. Francis Jacob – whose Bach recital (Zig-Zag, 5/01) remains a favourite – provides considered accounts of two significant solo organ works. Less abandon than Koopman, perhaps, but this is supremely refined playing and articulates the ambitions of an exceptionally distinguished project. Jonathan Freeman-Attwood (March 2010)

☆

St Matthew Passion

Sols; Bach Collegium Japan / Masaaki Suzuki

(BIS)

To embark on a second recording of the St Matthew Passion 20 or so years after an admired reading with many of the same musicians from Bach Collegium Japan might, one would imagine, have been governed by a specific set of motivations. On the evidence of this powerful, superbly framed and exceptionally judged account, Masaaki Suzuki may instead have reached a point where, over decades of intensely dedicated Bach performance, a revisiting simply became a necessary rite of passage – as it has for many before him.

Those who have traced Suzuki’s Bach direction of the last few years, alongside a burgeoning series of enterprising organ volumes, will have noticed a subtle but interesting shift in the realms of emotional risk and dramatic thrust. This is not to say that his performances of Bach’s choral works have ever been anything but an exploration of the inner meaning of how music, imagery and text converge in clearly projected ideals. But from the outset here, the music feels embedded in a broader and freer set of expressive ambitions than ever.

Suzuki’s vibrantly conceived vision extends to open-shouldered and passionately projected choral contributions, the lived-in storytelling of the burnished Evangelist of Benjamin Bruns (Peter’s denial is like a dagger to the heart), the switches between human frailty and febrile physicality of Christian Immler’s Jesus and Suzuki’s winning attribute of giving the music air and momentum at the same time. As a result, the ritual of each tableau and its reflective suite of arias is given genuinely memorable character. The opening growls with the same prescient foreboding and authority of the very best accounts of the past 70 years, whether Karl Richter’s first or Harnoncourt’s final reading.

The lingua franca of this recording is Suzuki’s incessantly perceptive blend of directly projected imagery and inward devotion, underpinned by theatrical fervour in the narrative; one never doubts Bach or Suzuki’s belief in its importance for mankind. The musicians convey it with infectious zeal in the white-hot conviction of tenor Makoto Sakurada’s open-throated Daughter of Zion sequence (from No 19, ‘O Schmerz!’); illuminated by light and shade in the instrumental accompaniment, soloist and chorus combine in an essay of unbearably imminent suffering. On the other end of the spectrum, the peroration offers a luminous solace – and what collective beauty Bach Collegium Japan bring to the heart-stopping ‘Mein Jesu, gute Nacht’ – to the redemption that will follow. No danger here of the final chorus ending in a morose slough of despond.

The quality of soloists in any recording of the St Matthew will significantly define its sustainable fortunes. Apart from a couple of underwhelming movements (‘Können Tränen’ is not vocally settled), the vast majority of arias represent the highest quality of Bach-singing. Damien Guillon is a commanding presence, with a quality of sound that carries both line and text with purpose and panache (listen to the opening of Part 2 as an exceptional example). Aki Matsui, a young and communicative singer, may not quite have the radiance and experience of Carolyn Sampson, but then few in this medium have. The latter’s wonderful ‘Aus Liebe’ reveals both a ravishing suspension of belief and pungent discipleship.

The high points are numerous: ‘So ist mein Jesus nun gefangen’, as luminously persuasive as you’ll hear (though Fritz Lehmann’s 1949 version takes some beating), Damien Guillon’s visceral ‘Erbarme dich’ – which grows in stature – and a ‘Mache dich’ from Christian Immler of grounded humanity. Yet there are dimensions of engagement between singers and instrumentalists that instil a sense of spontaneity in the variety and richness of timbre which I hadn’t heard to this extent in Bach Collegium Japan. The bass lines drive the music forwards, the crowd scenes declaim with quicksilver interpolations to the Evangelist’s cries and tempos are allowed to push and pull at key moments. Generic early music politesse is relegated to the shadows.

This reappraisal of the St Matthew (the earlier version from 1999 does appear studied and self-conscious in comparison, for all its estimable virtues) takes us on a journey which will continually enthral, move and surprise. If Bachians have found Suzuki’s performances a touch imperturbable on occasion, this recording throws down the gauntlet on almost every level. A revelatory reading of an eminent Bach interpreter in his prime. With each SACD coming in at over 80 minutes, it is squeezed on to two discs, offering excellent value. This certainly has the effect of bringing the two parts of the Passion closer together, to the serious benefit of our ears and imaginations. Jonathan Freeman-Attwood (April 2020)

☆

St Matthew Passion

Sols; Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists / John Eliot Gardiner

(SDG)

As has often been the case since his Bach Pilgrimage of 2000, the John Eliot Gardiner of this new, second recording of the St Matthew Passion is a changed conductor from that of the first. That was a studio version for DG (10/89), made when Gardiner was their Bach man enjoying the benefits of studio time and big-name soloists including Anthony Rolfe Johnson, Barbara Bonney and Anne Sofie von Otter; it was a state-of-the-art product but today can sound a little brisk and uninvolved in that 1980s way, particularly with regard to the shaping of the words. The new recording for the Monteverdi Choir’s own label is a live concert recording, with all the soloists except the Evangelist and Christus drawn from the ranks of the chorus. The live format is not so unusual in these economic times but choir soloists do seem to be dear to Gardiner for purely musical considerations, to judge from his use of them in several post-Pilgrimage projects. There is no doubt, however, that both elements pay off here.

The recording was made in Pisa Cathedral last September, but its foundations were laid over the previous six months in a 15-city tour which included a memorable performance in Brussels the day after the terror attacks there. The experience seems to have drawn the musicians together and intensified their commitment. If a Passion performance has no sense of community it has nothing, and this is surely the making of Gardiner’s account. This is a memorable and moving St Matthew, and for all the right reasons.

Musically it is very fine. The choir are excellent, of course, with a solid but clear and intimate sound even in the larger choruses, no end of expressive means in the chorales, and a thrilling quickness in the crowd choruses. Gardiner asks for a lot of quiet singing from them and they execute it with superbly controlled beauty. The orchestra is as skilled and musical as you like in their obbligatos, and exquisitely responsive to Gardiner’s subtle shapings – the string accompaniments to Christus’s recitatives, for instance, normally thought of as ‘haloes’, have never sounded so alert to the meaning of the Word. The experienced Evangelist of James Gilchrist and Christus of Stephan Loges are not to be faulted, and none of the nine young aria soloists is a weak link, to the extent that I’m loath to single out any one of them at the expense of another; suffice to say that each one lives up to their moment in the drama. Any or all of these are things you may find in other Matthews; but you will rarely find the same careful relishing of text, which treats the German words almost as rhythmical and textural sounds in themselves rather than theological pronouncements, as in Hannah Morrison’s lilting ‘Ich-h will hier mein Herze strenken’ or the choir’s impatient ‘L-lass ihn kreuzigen!’

What really makes this one special, however, is its emotional integrity, coming not from affected theatricality but from a pervading air of profound sadness. If ‘sad’ seems a weak word, it is not meant to be; it is just that the actors of this piece are not tearing at their hair but letting the weight of the events they are witnessing sink deep into their beings as individuals. The aching ‘Erbarme dich’ of alto Eleanor Minney and violinist Kati Debretzeni expresses it perfectly, assuming the pain further unto itself in a barely breathed da capo, like a wounded bird.

This is just one strongly moving moment among many, which more often than not are achieved through tender phrasing, confident (but never exaggerated) articulation and measured (but not sluggish) tempos. Though this at first may seem like a surprisingly light-touch reading from Gardiner, it is in fact one with a firmly controlled atmosphere of hurt and vulnerability. And when an individual performance does break through to something more outwardly emotional, as in Minney’s imploring ‘Können Tränen meiner Wangen’ or the heavy-laden strokes of Reiko Ichise’s gamba in ‘Komm süsses Kreuz’, it thus emerges all the more truly.

In his booklet-note Gardiner repeats his assertion that Bach’s great skill as an artist lay in his ability to write music with supreme power to console, and it is clear that this is what he has looked for here. That his considerable experience has enabled him to find it in such a thoughtfully moulded, expertly executed and deeply committed reading, so honestly communicative of its intent and so free of self-conscious monumentalism, sententiousness or melodramatics, is why I believe it to be one of his finest achievements. Lindsay Kemp (April 2017)

☆

St John Passion

Sols; Dunedin Consort / John Butt

(Linn)

Bach’s St John Passion gains more from the small-ensemble approach, I think, than its big sister, the St Matthew. Its emotional intimacy and urgency are better suited to the agility and immediacy a one-to-a-part performance brings, and the result can be a deeply compelling human drama. We have had several decent ‘chamber’ St Johns in recent years – including recordings from the Ricercar Consort (7/11), Cantus Cölln and Portland Baroque (both 3/12) – but this new one from John Butt and the Dunedin Consort really struck home for me by achieving its vital results without extravagant overstatement, overt ‘holiness’ or self-conscious marking-out of the work’s architecture. Indeed, naturalness and emotional honesty are what emerge from this tight-knit and perfectly paced ensemble Passion, in which Bach’s complex succession of recitatives, arias, choruses and chorales has surely seldom sounded so convincingly of a piece.

This is not, by the way, a polite way of saying that the performance lacks expressive variety or that performing standards are modest. On the contrary, the increasingly impressive Nicholas Mulroy’s alert, lightly coloured Evangelist strikes a balance in which declamation and lyricism are equally ardent and equally touching, while Matthew Brook is a supple and authoritative Christus. The use of harpsichord and organ together in the recitatives gives their joint story-telling a reassuringly grounded quality; there is nothing ‘ethereal’ in this St John and it is better for it. Both singers also perform with great effectiveness in the arias, where they are joined by Joanne Lunn (her ‘Ich folge dir gleichfalls’ is a joyous and sure-footed gem) and Clare Wilkinson, whose distinctive alto, straightforward in expression and tellingly connected to her speaking voice, lends fragility to ‘Von den Stricken’. Her desolate, almost whispered ‘Die Trauernacht’ in ‘Es ist vollbracht!’ also stabs to the heart.

When these four sing together in the choruses, to be joined by four more ‘ripieno’ singers, their sound is pressing and urgent but never hectoring, so that whether representing a crowd baying for blood or a group of chastened or horror-struck sinners, they come across as a gathering of real people rather than a disembodied chorus. The fact that you can sometimes recognise a soloist’s voice within the mix only adds to this impression of reality. Chorales are shaped with care and expressive sensitivity, but also never overcooked. The Dunedin Consort’s reliance on relatively young casts such as this has always brought their performances an uplifting freshness and immediacy in their recordings of Messiah, the B minor Mass and of course the St Matthew Passion, but in this harrowing piece it allows the sense of drama and personal identification to reach a higher level.

There is, however, another unique layer to this St John, for the piece is set in the context of the Good Friday Vespers liturgy of Bach’s Leipzig. This is where John Butt’s scholarly curiosity pays off, for he clearly sees the liturgical setting not as a dilution but an intensification of the work’s message. In this presentation the Passion – the service, not the oratorio – starts with an Easter chorale, first in Bach’s organ setting (played by Butt) and then sung by a congregation (actually the University of Glasgow Chapel Choir) alternating verses with a solo Mulroy. Then a short burst from a Buxtehude Praeludium leads straight to the opening chorus, nearly nine minutes after the disc has started. A similar sequence follows Part 1, and Part 2 is prefaced by another organ chorale. Immediately after the oratorio has ended (and let’s not pretend that the usual ending, a simple chorale to follow the glowing choral farewell that is ‘Ruht wohl’, does not sometimes sit strangely) comes Ecce quomodo moritur, a gentle funeral motet by the Renaissance composer Jacobus Handl Gallus (sung rather well by the University Choir again under James Grossmith). The reconstruction then ends with a few liturgical nuts and bolts and a final chorale for the congregation.

None of this extra material interrupts the Passion music itself – which, for the record, is a composite version representing what Bach’s uncompleted 1739 revision might have been like – and it can be programmed out if desired. But while you may not always want to sit through nine verses of chorale before getting down to business (or indeed listen to the half-time sermon, taken from a 1720 collection by Erdmann Neumeister, which is downloadable from the Linn website!), the effect of the violin swirls, pounding lower strings and intertwining oboe suspensions of that great opening chorus interrupting Buxtehude’s somewhat Gothic organ prelude certainly deserves more than one hearing. Butt makes a nice point in his booklet-note about how Bach’s Passion performances would have brought together in one project local singers of all abilities, from the soloists to the ‘motet choir’ to members of the congregation; and if his aim here has been to position this in the listener’s imagination and suggest the element of inclusive community that any Passion performance ought to have, well, it works for me. Lindsay Kemp (March 2013)

☆

St John Passion

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment & Polyphony / Stephen Layton

(Hyperion)

Stephen Layton’s outstanding new St John is about as state-of-the-art a Bach Passion recording as you’ll hear. For all its referencing various traditions, the overall signposting is pitched in the ‘middle of the road’ (and I mean that simply as one likely to satisfy as broad church as any available recording) and yet it appears remarkably fresh-sounding. Take as read the urgency, clarity, balance and declamatory unanimity of the chorus; Lindsay Kemp described the equivalent in Butt’s version where the effect of ‘a [single] voice within the mix only adds to this impression of reality’. Layton’s reality is about cultivating the focus of each sentiment with supreme corporate executancy.

Where Nicholas Mulroy’s Evangelist offers us intense reportage and touchingly personal asides, Ian Bostridge is the master story-teller who surveys all about him, impeccably delivering every nuance of every word. Some may find it too consciously etched, yet in the context of Layton’s carefully weighted reading it is both deeply subtle and consistently finessed.

Alongside the top-class and pliable choral singing of Polyphony comes the roll call of exceptional soloists – Nicholas Mulroy among them. Indeed, his ‘Ach mein Sinn’ conveys as rarely before the blend of inner mournfulness and savage panic which Bach inspires with this terse chaconne-inspired movement. More worldly still is Carolyn Sampson’s delectable ‘Ich folge’, where seasoned discipleship rather than bright-eyed innocence prevails.

The noble Christ of Neal Davies and the deeply felt singing of Roderick Williams complement the kaleidoscope of vocal expression here with their capacity for reflective commentary (‘Mein teurer’ is über-elegant), as does Iesytn Davies in a treasurable ‘Es ist vollbracht’. Such is Layton’s overall grip and understanding of the generic dramatic properties of the St John – especially in controlling tension and release – that we have here a perfect balance for the greater spontaneity of John Butt’s touchingly inhabited and personal journey. Jonathan Freeman-Attwood (May 2013)

☆

Christmas Oratorio

Sols; Concentus Musicus Wien & Arnold Schoenberg Choir / Nikolaus Harnoncourt

(DHM)

History has not judged kindly the revisiting of major Bach choral works by eminent conductors. Here is the exception. Nikolaus Harnoncourt recorded the Christmas Oratorio 35 years ago (and there was a live Unitel video in 1981) but this is a musician whose third reading of the St Matthew Passion in 2000 plumbed depths of understanding and characterisation of a quite different order from his previous accounts. Likewise, this significant and richly endowed contribution to the catalogue, whose defining rationale is the exploration of the Oratorio’s joyous and elegant poetic fervour, asks similarly penetrating questions. These are different challenges to the Passions in that Bach’s careful assembling of material for six “parts” or cantatas provides no obviously sustained “action” but, rather, tableaux from the majesty of Christ’s birth and the annunciation of the shepherds to the coming of the Three Wise Men as Epiphany approaches. Binding the themes and harnessing the material into an integrated whole for a single sitting (not necessarily inimical to Bach’s planning, despite being spread over the six Feast Days of Christmas, 1734-35) takes more than just a few well judged tempi and a generic Yuletide esprit.

Harnoncourt’s recording, taken from live performances in the Musikverein last Christmas, succeeds in this regard with uncanny freshness and generosity. Without a hint of world-weariness, each movement builds on the experience of what has been heard before (a device encouraged by Bach in his emollient and atmospheric instrumentation, and the decisive connections between each cantata). Bachians who know Harnoncourt’s Passion recordings will recognise the distinctive southern European classical tradition which has been brought to bear on his recent Bach performances. Witness the soft-grained radiance and ease, whether Mass or opera-inspired, which eschews an inward-looking and parochial outlook. Indeed, Harnoncourt is unique in his decisively pictorial and luminous landscape (in the more perennial oratorio tradition), alongside a highly developed ear for charting the work with kaleidoscopic, if occasionally maverick character. The springy choruses are bright but warm, spacious and unhurried, and packed with cathartic and lyrical dialogues between instruments and voices. The arias are also consistently probing, with fine performances from Christine Schäfer (“Nur ein Wink” is irresistible) and Bernarda Fink, whose “Schlafe” lives up to expectations (though one perhaps questions whether the faster speeds of the ritornelli reveal some patching).

Werner Güra’s narration takes a little time to warm up but by Part 2 he is in full swing with both unequivocal delivery and an impressive bravura in the unwieldy “Frohe Hirten”. Gerald Finley sings with open-hearted zeal and, despite occasional flatness, teams up touchingly with Schäfer in “Herr, dein Mitleid”. There is the odd rough edge and, inevitably, there are moments which will not be to everyone’s taste. But the unforced sweep of grandeur, complementing supple pastoral mosaics, marks out Harnoncourt’s Christmas Oratorio as a valuable and penetrating seasonal vision. Jonathan Freeman-Attwood (December 2007)

☆

Easter Oratorio

Retrospect Ensemble / Matthew Halls

(Linn)

Bach created the Easter Oratorio for Easter Sunday 1725, although some of the music was shrewdly parodied from a secular cantata composed some months previously for the birthday of Duke Christian of Saxe-Weissenfels. The Retrospect Ensemble’s orchestral playing and choral singing is of the highest quality, not surprising given that the personnel list features many alumni of the King’s Consort and other such expert Baroque ensembles. Matthew Halls neatly juxtaposes bustling vitality and an unforced conversational quality in the first part of the Sinfonia, with the three natural trumpets sounding particularly shapely and relaxed. The chorus is impressively disciplined and radiant in the opening chorus, during which rapid duet passages are delivered impeccably by James Gilchrist and Peter Harvey. Rachel Brown’s flawless flute is an eloquent counterpart to Carolyn Sampson’s enchanting gentleness in the aria “Seele, deine Spezereien”, and Halls controls its pizzicato bass-line with benevolent finesse. Gilchrist almost whispers the yearningly beautiful tenor part of “Sanfte soll mein Todeskummer” and the aria is all the more special because of Halls’s expressive handling of the delicate pastoral accompaniment of recorders and muted strings; I’ve heard many lovely performances of this aria but do not recall hearing the text communicated with such heart-rending consolation as this.

Halls partners BWV249 with Lobet Gott in seinen Reichen (written for Ascension Day 1735). The pairing is a sensible idea shared with previous discs from Leonhardt, Rilling and Suzuki but that need not dissuade anyone from savouring these outstanding performances. “Ach, bleibe doch, mein liebstes Leben” (Bach’s model for the Agnus Dei of the B minor Mass) has wondrous unison playing from the first violins and sweet eloquence from Iestyn Davies; the accompaniment of flutes, oboe and upper strings for Sampson’s singing in “Jesu, deine Gnadenblicke” is also interpreted perfectly. The excellent declamation, impeccable shaping of contrapuntal lines and flawless tuning of the Retrospect choir comes to the fore in the festive opening and closing choruses; the notably clean transparency between all four parts is achieved partly by an entirely male alto section but also by Halls’s astute ability to convey each strand of vocal and instrumental detail. David Vickers (May 2011)

☆

Motets

Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists / John Eliot Gardiner

(SDG)

Underpinning so much of Sir John Eliot Gardiner’s approach to Bach is identifying the provenance and essence of dramatic character, ‘mutant opera’ (as Gardiner calls it) found in genres – like the motet – which are not enacted but depend on perceptive rhetorical judgement within a fabric of rolling continuity. Bach’s motets may pay homage to forebears in scale, tone and technique but each one, especially revealed in this vibrant and questing new set, presses for fresh meaning with all the virtuoso means Bach could muster.

The motets have appeared as pillars of the Monteverdi Choir’s existence over five decades, punctuated by a notable recording for Erato in the early 1980s and most recently within selected programmes during the millennial Cantata Pilgrimage. For Gardiner, these works represent an endlessly fascinating tapestry of discovery which will doubtless continue to evolve, a body enhanced by the addition of Ich lasse dich nicht – a short motet once thought to have been by Bach’s great elder cousin, Johann Christoph, but now considered the work of the Young Turk.

Common to the Monteverdi Choir’s performances over the years are their inimitable textual projection, clarity of line, rhythmic rigour and an overriding sense of expectancy and flair, just occasionally slipping a little too eagerly into exaggerated gesture. Gardiner asks for more pinpoint delicacy, quicksilver contrast and lightness than ever and illuminatingly inwardda camera dialoguing between voices. For all the pages of sprung bravura and purpose, especially in Lobet den Herrn and Singet dem Herrn, there are as many periods of elongated and poignant restraint.

There is no more compelling example than the soft, controlled climate of the final contemplative strains of Fürchte dich nicht, where we have an extraordinary representation of the precious mystery of belonging to Christ. The soprano motif on ‘und dein Blut, mir zugut’ (‘thy life and thy blood’) is uttered with such sustained and ritualised other-worldliness (track 15, 5'38") that the risk of disembodiment is only allayed by the Monteverdi Choir’s captivating certainty of line as the devoted soul drifts heavenwards.

One of the most striking features in this new collection, as I mentioned previously, is how attentive Gardiner is to the individuality of each of the motets. This might seem a time-honoured ambition and yet, for all the admirable qualities of, say, the RIAS Kammerchor under René Jacobs or the more recent reading from Philippe Herreweghe and Collegium Vocale Gent, neither of these brings as ambitious a kaleidoscopic challenge to the listener in identifying renewed character and meaning as Gardiner aspires to. Indeed, Herreweghe recently went as far as to say that ‘a groundbreaking reading is not necessary’.

Gardiner would disagree. How lucidly Der Geist hilft (that short but compact work written for the funeral of Ernesti, the old Rector of St Thomas’s, in 1729) sets out to reflect the infirmities of man gradually imbued with the intercessions of the Holy Spirit. Here we have something more perspicacious than merely good pacing: the Monteverdi singers narrate this play of uncertainty and the growing anticipation of understanding God’s will with such corporate and dynamic purpose that, even when the two choirs converge in an affirming four-part double fugue, we never feel quite out of the woods. The tantalising prospect of salvation is only truly satisfied at the final cadence of a luminously directed chorale.

Some of these interpretative risks may not suit those who prefer a less articulated, more abstract, soft-edged and generally expansive landscape. Singet dem Herrn is typically exuberant in its outer ‘concerti’ but the unique double-choir juxtaposition of chorale and free contrapuntal ‘rhapsody’ could perhaps have yielded more genuine contemplative warmth. Indeed, Gardiner rarely delivers a comfortable ride and yet what brilliant visions emerge, most strikingly in the central work, the five-part Jesu meine Freude, riding – literally – the storm of the love of the flesh, Satan, the old dragon and death.

Throughout this masterpiece, terrifying, quasi-‘turba’ (crowd) scenes are viscerally offset against an ethereal quest for redemption. ‘Es ist nun nichts Verdammliches’ (‘There is now no condemnation’) has surely never enjoyed such a mesmerising volley of declamation and rich illusion over a short space as Gardiner summons, while ‘Trotz dem alten Drachen’ (‘Despite the old dragon’) spits out its irascible consonances only to be disarmingly defied by the elevated purity of ‘in gar sichrer Ruh’ (‘in confident tranquillity’) – all this in contrasting tableaux of ever-surprising emotional impact. If the listener is often left gasping, this is caused not only by vocal singularity of purpose but by the discreet and graphic responsiveness of the instrumental continuo players, among whom the bassoon here (and in Komm, Jesu, komm) contributes with knowing effect.

As you would imagine, surprises abound – some of which take a little getting used to. Gardiner challenges orthodoxy in how these a cappella holy grails are fundamentally signposted and he does so, almost always, with persuasive passion and genuine zeal. High-wire artist Philippe Petit is a fitting cover image to this important landmark in highly recommended, high-stakes performances. Jonathan Freeman-Attwood (August 2012)

Adaugă un comentariu

© 2024 Created by altmarius.

Oferit de

![]()

Embleme | Raportare eroare | Termeni de utilizare a serviciilor

Pentru a putea adăuga comentarii trebuie să fii membru al altmarius !

Alătură-te reţelei altmarius