cultură şi spiritualitate

Poor and small, Portugal was at the edge of late medieval Europe. But its seafarers created the age of ‘globalisation’, which continues to this day, as Roger Crowley explains.

In the dying years of the 15th century Portugal surprised the world. Vasco de Gama's landfall on the Indian Coast in May 1498 was so unexpected that it strained credibility. A garbled rumour reached the Venetian diarist Girolamo Priuli that 'three caravels belonging to the king of Portugal have arrived at Aden and Calicut in India and that they have been sent to find out about the spice islands and that their captain is Columbus'. His initial response was a mixture of shock and disbelief: 'This news affects me greatly, if it's true', he wrote. 'However I don't give credence to it.' Priuli was registering the first reaction to a seismic shift in the comprehension of our planet: Gama's voyage had finally demolished the ancient authority of Ptolemaic geography, which held the Indian Ocean to be a closed lake.

Priuli's misattribution anticipated the extent to which Columbus has come to dominate the historiography of the age of discoveries. While 1492 is conventionally the watershed moment, the largely forgotten role of the Portuguese in begetting the early modern era is also immense. For a century they led the way in connecting the hemispheres and giving its people a new sense of their place in the world. Alongside the age of Columbus, there is an equally significant Vasco da Gama era of history.

Gama's rounding of the Cape of Good Hope was the result of 60 years of effort. Portugal was poor, small and marginal to the arena of the Mediterranean world, but its long Atlantic coast gave it unique skills in navigation, cartography and open-sea sailing and it had developed a precocious sense of national identity. The search for India was a stop-start affair, concerned initially with slaving and a hunt for gold – Henry the Navigator's reputation as a founding father of scientific exploration has now been largely dismantled – but decade by decade the Portuguese worked their way down the west coast of Africa, exploring its great rivers and mapping the coastline. Lisbon, open to the sea, gave Europe a first taste of a world beyond itself. The African voyages transformed the city into the go-to place for new ideas about cosmography. The produce unloaded on its shores – spices, slaves, parrots, sugar – conjured up exotic possibilities. In the 1490s, as Columbus sailed west, Portuguese navigators finally cracked the code of the South Atlantic winds.

The 60-year apprenticeship slogging down the African coast enabled the Portuguese to develop a methodology of knowledge acquisition based on first-hand observation. They became expert observers and collectors of geographical and cultural information. They garnered this with great efficiency, scooping up local informants, employing interpreters, learning languages, observing with dispassionate scientific interest, drawing the best maps they could, refining their deployment of diplomacy and violence. Astronomers were sent on voyages; the collection of latitudes became a state enterprise. Information was fed back into a central hub, the India House in Lisbon, where everything was stored under the crown's direct control to inform the next cycle of voyages. This system of feedback and adaptation was highly effective. It was accompanied by a rapid expansion in cartographic knowledge.

Following Gama's arrival on the Malabar Coast, the Portuguese put all this to good use. Within a decade of bursting into the Indian Ocean, they understood, pretty accurately, how its 28 million square miles worked, its major ports, the rhythm of its monsoons, its navigational possibilities and communication corridors. They had a clear grasp of the ocean's choke points and rapidly constructed a geo-strategic vision for controlling them. Under two inspirational leaders, Francisco de Almeida and Afonso de Albuquerque, they built a prototype maritime empire that would form the template for European colonial expansion. Without the human resources to hold territory, it relied on the establishment of fortified bases at key strategic points around the rim of the ocean, dependent on mobile sea power and ship-borne cannon. They acquired Mozambique on the Swahili Coast, Ormuz at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, Goa, and Malacca on the Malay Peninsula, all critical hubs in the long-distance trade that moved goods between Egypt and China.

The Portuguese advance was rapid. They accidentally discovered Brazil in 1500, having already reached Newfoundland and Greenland. They first took Goa, destined to be the seat of their Indian empire, in 1510 and Malacca in 1511. Albuquerque despatched embassies to Burma, Thailand and Sumatra in the same year. They reached the Spice Islands in 1512; a first European mission to seek diplomatic relations with the Ming dynasty in China landed at Canton in 1516. They stepped ashore in New Guinea in 1525 and Japan in 1543. They may have been the first to visit Australia. The Portuguese navigator Fernão de Magalhães (Magellan) had led Spanish ships that achieved the first circumnavigation of the world, though he himself died during the voyage. In 50 years Portuguese mariners had touched every continent except Antarctica and possibly Australia.

The impetus for this burst was summarised by the first words spoken at Gama's landfall. Asked why they had come, the man sent ashore, João Nunes, replied: 'We came in search of Christians and spices.' Religious mission, to outflank Islam and to convert, would intertwine with commerce. Within the Indian Ocean, the Portuguese created a formal empire, largely through violence combined with diplomacy and legitimate trade. Beyond, in dealings with the old civilisations of China and Japan, they arrived as supplicants, carrying goods and religious messages.

The Arrival of the Portuguese in Japan, Namban screen, Japan c.1600.

The Arrival of the Portuguese in Japan, Namban screen, Japan c.1600.

With the exception of Brazil, the Portuguese, unlike the Spanish, did not conceive an empire of territorial possession. There were far too few of them and mortality in the tropics was high. Their early ambition to control the whole Indian Ocean relied on no more than 3,000 men at any one time. It was a world, in its more pacific manifestations, of mobile trading links, held together by ports and forts and redoubtable sailing ships, up to a size of 1,000 tons. In the process they shunted people around the world. The Portuguese exported themselves in sufficient numbers at times to worry the civic authorities at home. Emigration came in many forms, both voluntary or compulsory: as servants of empire – colonial administrators, factors and soldiers – sailors, merchants, fortune seekers, missionaries and convicts. Because these emigrants were largely male, they were formative in the creation of mixed race communities. In Goa this was a matter of state policy. Men were encouraged to marry local women, giving rise to a unique Luso-Indian society. A hallmark of the Portuguese diaspora has been the creation of creole societies.

***

The willingness to explore, to push beyond the limits of the known world, took many forms. Men went in search of gold, to seek religious converts, out of wanderlust, as ambassadors, merchants, spies, smugglers and pirates. Many just vanished off the map. The Arab-speaking Pêro da Covilhã, sent via Cairo to seek out the spice routes in advance of a final push for India, criss-crossed the Indian Ocean disguised as a Muslim merchant, visited Mecca and resurfaced in Ethiopia 30 years later. Bento de Góis, travelling as an Armenian, left Goa in 1602 and took five years to reach China through the Himalayas. Pedro Teixeira performed the remarkable feat of travelling upstream the length of the Amazon in the 1630s. Jesuits were in Bhutan and Tibet in the same period: missionaries were particularly indefatigable travellers and language learners. By the middle of the 17th century they had baptised probably over a million people from Mozambique to the Far East. They were most successful in Japan, creating about 300,000 converts until their activities induced a wave of xenophobia and they were either expelled or killed.

Luís Vaz de Camões, whose epic poem The Lusiads created a founding mythology for the heroism of exploration, exemplified the sometimes desperate qualities of Portugal's adventurers. He was the most widely travelled poet of the Renaissance: a man who lost an eye in Morocco, who was exiled to the East for a sword fight, who was destitute in Goa and shipwrecked in the Mekong Delta (he swam ashore clutching his manuscript above his head while his Chinese lover drowned). 'Had there been more of the world', Camões wrote of the Portuguese explorers, they 'would have discovered it.'

The Portuguese were also pathfinders in some of the bleaker aspects of European expansion. They invented Atlantic slavery. Tapping into an ancient trade in black slaves from sub-Saharan Africa, they were bundling captured people into cramped caravels back to Portugal from Senegambia as early as the 1440s. The chronicle account of human beings unloaded onto an Algarve beach in 1444 under the gaze of Henry the Navigator is a founding text for Europe's slave trade:

Some held their heads low, their faces bathed in tears as they looked at each other; some groaned very piteously, looking towards heavens fixedly and crying out aloud, as if they were calling on the father of the universe to help them; others struck their faces with their hands and threw themselves full length on the ground … To increase their anguish still more, those who had charge of the partition then arrived and began to separate them one from another so that they formed five equal lots. This made it necessary to separate sons from their fathers and wives from their husbands and brother from brother … mothers clasped their other children in their arms and lay face downwards on the ground, accepting wounds with contempt for the suffering of their flesh rather than let their children be torn from them.

As the numbers grew the techniques became industrialised. They were soon arriving in Portugal 'piled up in the holds of ships, 25 or 40 at a time, badly fed, shackled together back to back'. The Portuguese were Europe's largest importer of captured human beings. By the mid-16th century probably 10 per cent of the population of Lisbon were black slaves, but it was with the settlement of Brazil and the demand for labour in its plantations and gold mines that transatlantic slavery took off. The trading post of Elmina on the coast of Ghana, centre of the gold trade, became in turn the efficient holding pen and point of departure for tens of thousands of people. They exited out of the Door of No Return onto ships colloquially referred to as coffins. Half died in transit. Over three hundred years between three and five million people were forcibly moved to Brazil alone, a colossal involuntary migration.

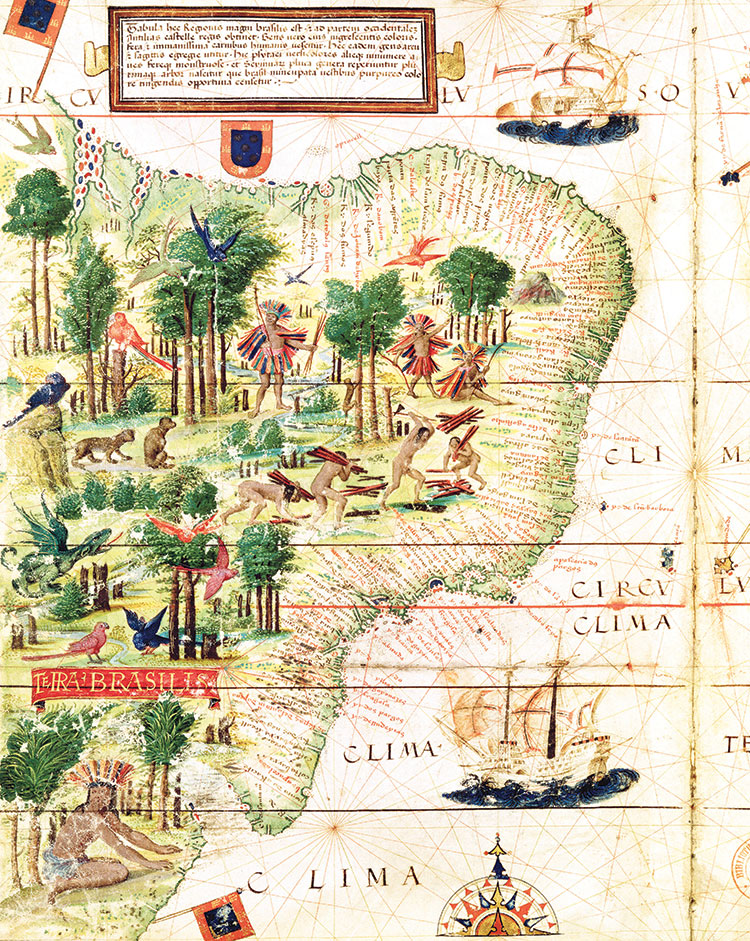

A chart of Brazil by the Portuguese cartographer Fernão Vaz Dourado, 1571.

A chart of Brazil by the Portuguese cartographer Fernão Vaz Dourado, 1571.

The slave ships were an inevitable breeding ground for disease but the wider mobility of the Portuguese themselves contributed to the spread of pathogens around the world. Gama's ships and their successors may have introduced syphilis to India and beyond: to Timor, where it was referred to as the Portuguese disease, and to China. Like the Spanish, they carried with them into South America the diseases of Europe such as tuberculosis, mumps, yellow fever and TB. Smallpox and typhus proved particularly devastating to the native peoples of the Amazon.

***

The development of a Portuguese commercial empire in the 16th century, stretching from South America to China, initiated long-range trading networks. It saw the start of a system that could exchange goods across hemispheres. Lenses travelled from Germany to China, elephants from Sri Lanka to Vienna. All passed through Lisbon as the major hub and the clearing house for goods in and out of Europe. The historian John Russell-Wood has reconstructed examples of the kinds of intricate exchanges that took place. A clock made in Flanders was exported from Lisbon. Carried to the Portuguese hub at Goa, it found no buyers and was taken on to Malacca on the Malay Peninsula where it was exchanged for sandalwood (probably from Sri Lanka or Southern India). The sandalwood was shipped to Macao where it was sold for gold. The gold was carried by Portuguese middlemen to

Nagasaki, where it was used to buy a valuable work of art, a painted screen. This was transported back to Goa and eventually returned to Lisbon. Cloves that would be sold in Morocco made the journey from Ternate in Eastern Indonesia, via Malacca, Cochin and Lisbon and would be exchanged for wheat that would find its way to West Africa. Venetian glass beads and Flemish brass pans, carried via Lisbon to Elmina, might be exchanged for pepper, gold, slaves and monkeys, that would be shipped back to Bristol, Antwerp and Genoa. All these commodities travelled in Portuguese vessels.

Within the separate oceans triangular trades developed. Goods circulated in the Atlantic Ocean between Portugal, Angola and Brazil. Within the Indian Ocean and beyond, valuable trading cycles often never touched the mother country at all. Goa became the hub of one inter-Indian Ocean trade, moving goods and foodstuffs between the Swahili coast, the Persian Gulf and western India; Portuguese Malacca was the centre of another, onwards to the Spice Islands, China and Japan. When the Ming dynasty turned inwards and banned all foreign trade, Portuguese merchants cornered an intermediary market between China and Japan, shuttling silk, gold and porcelain from Macao to Nagasaki, returning with Japanese silver and copper. It gave them a lucrative role in Far Eastern commerce. Gold, initially from West Africa then from the kingdom of Mutapa in southern Africa and later Brazil, was the lubricant of these trades. The Portuguese had a major role in bullion flows, reshaping economies in their wake. They were instrumental in shifting Spanish silver across the world as far as China, which had a preference for the metal, and initiating a price revolution in India. They were facilitators in technology transfer, too, introducing firearms into Japan in 1543, where they were quickly adopted, together with pilot charts. The Jesuits, although limited in their success in China, interested the ruling dynasty in astrolabes and other astronomical instruments, constructed an observatory in Beijing and produced the first Chinese maps to show the Americas.

This long-distance interchange of commodities extended to plants and foodstuffs. As with many areas of foreign contact, there was a genuine curiosity in the flora of new worlds. The work of the Portuguese Jewish doctor, Garcia de Orta, a pioneering empirical botanist and author of a book on the herbs and plants of Goa, aroused wide interest in Europe, via translations and plagiarised versions. As the connections between the furthest reaches of their empire grew stronger, deliberate experiments were made to transplant crops from one continent to another, sometimes by carrying whole plants, more often by taking seeds on their voyages. These initiatives made a major contribution to the dissemination of plant species, food supply and diet across the globe. They introduced spices from the East Indies to Brazil, returning cashews, peanuts and peppers to both China and India, to which they also introduced pineapples and tobacco. There was a significant species exchange across the Atlantic between Brazil and Africa: maize, manioc, cashews, sweet potatoes and peanuts travelled east on Portuguese ships, returning from the West Coast of Africa with red peppers, bananas, yams. From Portugal, vegetables, citrus fruits and sugar cane reached the New World. The Jesuits sent Chinese boars to Portugal. Filo pastry from North Africa led to the samosa in India and the spring roll in China; rhubarb came to Europe from South China, satsumas from Japan. Genetic material was being shunted around the world.

'How the Portuguese whip their slaves when they run away', from Relation d'un Voyage fait en 1695, 1696 & 1697 by François Froger.

'How the Portuguese whip their slaves when they run away', from Relation d'un Voyage fait en 1695, 1696 & 1697 by François Froger.

The interactions between the Portuguese and other peoples created an immense quantity of information. The first century of Portuguese discoveries saw a successive stripping away of layers of medieval mythology about the world and the received wisdom of ancient authority – the tales of dog-headed men and birds that could swallow elephants – by the empirical observation of geography, climate, natural history and cultures that ushered in the early modern age. It stimulated the production of a vast and varied output of written material, which seeped into other European languages. By the 1600s, writers such as Richard Hakluyt and Samuel Purchas were transmitting Portuguese knowledge into English.

If the Portuguese described what they saw, they were also seen in turn as objects of curiosity, fear and wonder. The Sinhalese were perplexed by their endemic restlessness and their eating habits, declaring them to be 'a very white and beautiful people, who wear hats and boots of iron and never stop in one place. They eat a sort of white stone and drink blood'. The Japanese scrutinised the namban-jin (the Southern Barbarians, because they arrived via Korea) and scrupulously illustrated their ships, their ballooning pantaloons and strange hats in comic detail, lampooning their mannerisms and their large noses as well as the appearance of the tall, black-robed Jesuits. Across the trading world images and artefacts of the Other reflected a new trans-hemispheric awareness. Many of the cultures to which the Portuguese travelled came to produce hybrid works of art: the Madonna and child as Chinese figurines; carved ivory boxes from Sri Lanka mixing Hindu deities with representations of European kings and images from Dürer; Portuguese nobles in palanquins in Goan art and their ambassadors in Mughal miniatures; Benin bronzes of Portuguese soldiers with muskets and crossbows; and carved salt-cellars topped by miniature European ships. Much of this art was religious. The missionary fathers worked tirelessly at Christian presentation in local idioms and, from as faraway as China, where blue and white porcelain was produced bearing the arms of Manuel I, artefacts were being created for distant markets.

A great deal of this exotica, along with foodstuffs, ethnographic 'specimens' (captured slaves or emissaries from beyond) plants and animals, worked its way back to Europe. It sharpened both an awareness of other cultures and the perspective on the West's place in an expanded world. Particularly famous were two animals sent to Manuel I around 1513: a white elephant and an equally rare white rhino; the first live specimen in Europe since the time of the Romans. Manuel delivered the white elephant to the pope under the command of his ambassador, Tristão da Cunha. A cavalcade of 140 people, including some Indians, and an assortment of wild animals – leopards, parrots and a panther – entered Rome, watched by a gawping crowd. A second gift, the rhino, drowned en route, but Dürer was able to produce a passable likeness armed only with a rough sketch.

***

The appreciation of the world beyond and its artefacts – the namban paintings from Japan, intricate worked ivories from Benin, inlaid chests from West India – expanded Europe's ideas of visual possibilities and their wonder. One observer of the people of Sierra Leone noted them to be 'very skilled in manual work, they produce salt-cellars in ivory and spoons and whatever task one sketches for them, they carve in ivory'. Dürer was amazed by such artefacts: 'All the days of my life I have seen nothing that rejoiced my heart so much as these things, for I saw amongst them wonderful works of art, and I marvelled at the subtle ingenia of people in foreign lands. Indeed, I cannot express all that I thought there.'

A Portuguese merchant is greeted by his Indian household, early 16th century.

A Portuguese merchant is greeted by his Indian household, early 16th century.

Portugal's commercial dominance of large swathes of the world lasted little more than a century. Yet the images, transmissions and trades that it engendered left a significant and long-lasting influence on the culture, food, flora, art, history, languages, and genes of the planet, together with dark shadows: the exploitation, violence and slavery that its colonial successors inherited. When the Dutch first dismantled its spice empire they found that Portuguese was the lingua franca of the commercial world from China to Brazil and were compelled to use it.

Writing about the first decades of Portuguese exploration the 16th-century historian João de Barros described the viceroy of India, Francisco de Almeida addressing an Indian raja with the assertion that 'the principal intention of his king Don Manuel in making these discoveries was the desire to communicate with the royal families of these parts, so that trade might develop, an activity that results from human needs, and that depends on a ring of friendship through communicating with one another'. It was a prescient awareness of the origins and benefits of long-distance trade: the runaway train of globalisation that started with Vasco da Gama.

Roger Crowley's Conquerors: How Portugal Seized the Indian Ocean and Forged the First Global Empire was published by Faber & Faber in September 2015.

Adaugă un comentariu

© 2024 Created by altmarius.

Oferit de

![]()

Embleme | Raportare eroare | Termeni de utilizare a serviciilor

Pentru a putea adăuga comentarii trebuie să fii membru al altmarius !

Alătură-te reţelei altmarius