cultură şi spiritualitate

https://www.gramophone.co.uk/features/article/the-50-greatest-js-ba...

Cello Suites

Steven Isserlis vc

(Hyperion)

For Isserlis the Suites suggest a meditative cycle on the life of Christ, rather like Biber’s Mystery Sonatas. He points out that this is “a personal feeling, not a theory”, but it has to be said that once you know that he is thinking of the Agony in the Garden during the darkly questioning Second Suite (the five stark chords towards the end of the Prélude representing the wounds of Christ), the Crucifixion in the wearily troubled Fifth or the Resurrection in the joyous Sixth, it adds immense power and interest to his performances.

But then, this is also the most wonderful cello-playing, surely among the most consistently beautiful to have been heard in this demanding music, as well as the most musically alert and vivid. Not everyone will like the brisk tempi (though the Allemandes, for instance, gain in architectural coherence), but few will fail to be charmed by Isserlis’s sweetly singing tone, his perfectly voiced chords and superb control of articulation and dynamic – the way the final chord of the First Prélude dies away is spellbinding. There are so many other delights: the subtle comings and goings of the Third Prélude, the nobly poised Fifth Allemande, the swaggering climax that is the Sixth Gigue – I cannot mention them all. Suffice to say that Isserlis’s Bach is a major entrant into an already highly distinguished field, and a disc many will want to return to again and again. Lindsay Kemp (July 2007)

☆

Cello Suites

David Watkin vc

(Resonus)

As with so much mainstream repertoire, the catalogue is so full of recordings – good and bad – that there often has to be some form of abstract justification to qualify any further additions. David Watkin’s profound musicianship, though, is more than enough to accelerate this recording of Bach’s Cello Suites to the top of the tiny league of ‘definitive’ recordings, beyond the infinitesimal care of Ditta Rohmann (Hungaroton, 5/14, 11/14), the meticulous intellectualism of Anner Bylsma (Sony, 7/81, 1/93) or even the refined warmth of the benchmark Fournier performances (Archiv, 3/89): all encapsulate the vital elements of these works but none succeeds completely in covering them all.

Watkin plays the first five suites on a cello by Francesco Ruggieri – a luthier contemporary of Bach’s whose instruments are famed for their warmth of tone – and the sixth on a rare five-string cello by the Amati brothers of the same period. But the extraordinarily resonant sound he makes is probably less to do with the instruments than with the playing itself, which is warm, expansive, generous and friendly. That is not to say that this performance is not of the highest level intellectually and technically: it is, and largely because of its appreciation of these suites as not just dances but discourses almost verbal in their directness. It is as if all the work that Watkin has ever done on these pieces has been absorbed absolutely and then reproduced in a performance that is able to be completely original in its voice at the same time as never producing a phrase that jars in its unsubtlety, or presents an ego that overarches the music.

That generosity of artistry directly results in some movements that are not only opened up to the listener as the masterworks they are but as paeans of heart-cracking joy. If you only buy this disc for the Prelude of the C major Suite, for exactly that reason, it will be money well spent. Caroline Gill (June 2015)

☆

Solo Violin Sonatas & Partitas

Rachel Podger vn

(Channel Classics)

As a matter of tactics disregarding the printed order of the works, this second disc opens in the most effective way with a joyous performance of the ever-invigorating E major Preludio. At once we can recognize Podger's splendid rhythmic and tonal vitality (not merely Bach's marked terraced dynamics but pulsatingly alive gradations within phrases), her extremely subtle accentuations and harmonic awareness (note her change of colour at the move from E to C sharp major in bar 33), are all within total technical assurances. The Gavotte en Rondeau is buoyantly dance-like, and in the most natural way she elaborates its final statement (her stylish ornamentation throughout the Partita is utterly convincing). She takes the Giga at a restrained pace that allows of all kinds of tiny rhythmic nuances. Only a rather cut-up performance (for my taste) of the Loure stops this being one of the most enjoyable E major Partitas I can remember.

In the sonatas she shows other sterling qualities. She preserves the shape in the A minor Grave's ornate tangle of notes; she judges to a nicety the balance of the melodic line against the plodding accompanimental quavers of the Andante; she imbues the C major's Adagio with a hauntingly poetic musing atmosphere, and her lucid part-playing of its Fuga could scarcely be bettered. In the Fuga of the A minor Sonata, however, she unexpectedly allows herself considerable rhythmic freedom in order to point the structure. The final track is a stunning performance of the C major's closing Allegro assai which would bring any audience to its feet. This disc is a natural for my Critic's Choice of the year. Lionel Salter (December 1999)

☆

Solo Violin Sonatas & Partitas

Monica Huggett vn

(Erato)

With these impressive performances (on her beautiful-toned Amati) of the Solo Sonatas and Partitas Monica Huggett sweeps other baroque interpretations off the board. She nails her colours firmly to the mast in her printed introductory note (which follows an uncommonly perceptive and informative commentary on the music by Mark Audus): her aim, she says, is a characteristically bright and sweet seventeenth-century timbre, and she declares herself less interested in the virtuoso aspect of the music, more in the “interior spirituality of the sonatas and the gracious elegance of the partitas”. That certainly does not imply any absence of virtuosity: there have been few recordings of these pillars of the repertoire so impeccable in intonation and so free from any tonal roughness.

Her rhythmic flexibility (very marked in the Chaconne) may upset some traditionalists, but it gives her readings a thoughtfully spontaneous air, and is always applied to clarify the phrasing. The B minor Corrente and D minor Allemande, for example, become more expressive through this subtle phrasing, and her G minor Presto and E major Prelude are not merely mechanically fluent. She is adept at balancing the interplay of internal parts and at preserving continuity of line (as in the D minor Sarabande) and rhythmic flow despite the irruption of chords: only in places in the gigantic C major Fugue did I feel this under strain and at the start of the B minor Bourree lost. There is a lively bounce in her D minor Courante and E major Gigue, and she is splendidly neat in the double of the B minor Courante and in the C major’s finale. For the most part she is very sparing with embellishments, decorating ritornellos of the E major Gavotte and the first half (only) of the D minor Sarabande, but then suddenly becomes lavish in the repeats of the A minor Allegro. Monica Huggett’s musicianly readings are very rewarding and are warmly to be recommended. Lionel Salter (January 1998)

☆

English Suites Nos 1, 3 & 5

Piotr Anderszewski pf

(Warner Classics)

This is a glorious disc. Simply glorious. Anderszewski and Bach have long been congenial bedfellows and the Pole’s playing here is compelling on many different levels. To start with, there’s the sense of sharing the sheer physical thrill of Bach’s keyboard-writing. This is particularly evident in faster movements such as the fierce and brilliant fugal Gigue that concludes the Third Suite, or, in the E minor Fifth Suite, the extended fugal Prelude and the outer sections of its Passepied I. Common to all is a sense of being fleet but never breathless, with time enough for textures to tell.

At every turn you get the sense of Bach flexing his compositional muscles in these early keyboard suites. There is of course nothing innately ‘English’ about them and the origin of their title is shrouded in mystery, though Bach’s earliest biographer Johann Nikolaus Forkel speculated that it reflected the nationality of the suites’ (unknown) dedicatee. As with the keyboard partitas (of which Anderszewski so memorably recorded the First, Third and Sixth for Virgin Classics back in 2001 – 1/03), there’s a sense of Bach demonstrating just how much variety he could introduce into a suite built around the common elements of Prelude, Allemande, Courante, Sarabande and Gigue. In Anderszewski’s hands the First, Third and Fifth very much occupy their own worlds in terms of mood. Thus there’s a palpable delight in the rhythmically ungainly theme from which the Gigue of the First Suite is fashioned and Anderszewski’s way with Bach’s counterpoint is at once strong-jawed and supple. We’re always aware of the re entry of a fugue subject, for instance, as it peeks through the texture in different registers or reappears stood on its head, yet it’s never exaggerated as is sometimes the tendency with less imaginative pianists.

And how Anderszewski can dance – at least at the keyboard – in a movement such as the Prelude of the Third Suite, urged into life through subtle dynamics, voicings, articulation and judicious ornamentation. A very different kind of dance reveals itself in the Gavotte II of the Third Suite, a musette in which he takes a more impish view than many, the sonorous drone effect contrasting delightfully with the tripping upper lines. The way he has considered the touch and dynamic of every phrase means that these are readings that constantly impress with fresh details each time you hear them.

Even the most apparently unassuming numbers, such as the Second Bourrée of the First Suite or the Passepied II of the Fifth, gain a sense of intrigue as he re examines them from every angle, again bringing multifarious shadings to the music. And it all flows effortlessly – though I’m sure the journey has been anything but that. Highlights abound: in the murmuring Courante of the Third Suite, the Pole’s reactivity leaves Maria João Pires sounding a touch unsubtle – which is really saying something. This is followed by one of the most extraordinary readings of the Sarabande I’ve ever heard. While Pires revels in its echoing harmonies, Anderszewski draws you daringly into his own world, as Bach’s initially grandiose sonorities become more and more withdrawn. This whispered intimacy extends into his insertion of an ornamented version of this movement, entitled ‘Les agréments de la même Sarabande’, which proves a masterclass in audacious ornamentation, yet never overburdening Bach’s melodic lines. In fact the effect here is truly meditative. Fittingly, there is a long silence before the limpid Gavotte.

Are there any caveats? Some might find the basic pulse of the First and Fifth Sarabandes perhaps too slow. To me they work precisely because he teases so much out of each line. They have a Gouldian intensity that draws you ineluctably in without any of the Canadian’s wilfulness.

You can be in no doubt of the thought that has gone into this enterprise, from Anderszewski’s ordering of the courantes of the First Suite, which he explains in the booklet, to the programming of the suites themselves, opening the disc with the Third rather than the more quizzical First. And at every turn, he harnesses the possibilities of the piano in the service of Bach; the result is a clear labour of love, and one in which he shines new light on old music to mesmerising effect, all of which is captured by a warmly sympathetic recording and an engaging booklet-note by Mark Audus.

Anderszewski’s CDs are all too infrequent, so let’s cherish this one. Harriet Smith (February 2015)

☆

French Suites

Murray Perahia pf

(DG)

Recent research shows that, though divorce rates are falling in the UK, there’s an upward trend among the over-50s. The theory is that now we’re longer lived, we’re less inclined to settle for familiar domesticity when we could be off sailing the seven seas. That might account for Murray Perahia – 70 next April – calling time on Sony Classical after an apparently happy marriage of 43 years. So here he is setting off for pastures new with DG; and, honeymoon period or not, the fit looks good with this, his first recording of Bach’s French Suites, pieces that have been in his concert repertoire for decades.

In the booklet interview Perahia reveals that his first encounter with Bach in concert was as a teenager when he heard Pablo Casals conducting the St Matthew Passion at Carnegie Hall. Perahia and Casals, though temperamentally very different, have in common a sense of bringing across Bach the man rather than Bach the god. And that’s particularly pertinent in the French Suites, the most approachable – though no less inspiring or perfectly conceived – of Bach’s keyboard suites.

As we expect from Perahia, everything sounds natural and inevitable. Ego doesn’t come into it: rather, he acts as a conduit between composer and audience with a purity that few can emulate (I’m put in mind of Goode, Brendel and the new boy on the block, Levit). Ah yes, ‘intellectual’ pianists, I hear you mutter. But to describe any of these figures as merely ‘intellectual’ would be to miss out the huge humanity of their playing.

Take the opening Allemande of the Fourth Suite: in Perahia’s hands it’s a sinuous, conversational affair and the way he colours the lines as Bach reaches into the upper register is done with enormous subtlety. Or sample the Sarabande of the same suite, simultaneously intimate yet with true gravity. He brings out the left hand’s largely stepwise motion to a nicety – sometimes reassuring, sometimes questioning.

Perahia is not an artist who takes Bach to extremes: he doesn’t intervene in the way that Maria João Pires or Piotr Anderszewski can do to such mesmerising effect. Take the gigues, for instance. Some take the buoyant Gigue of the Fifth Suite at a more headlong pace, yet Perahia’s feels just so: the rhythms are bright and springy, full of energy without freneticism, and joy is palpable in every note. Or that of the Second Suite, which again sounds completely inevitable, even when he spices it, on its repeats, with dazzlingly daring ornamentation that underlines the inherent dissonances within Bach’s counterpoint. Compared to this, Peter Hill seems a touch staid, Ekaterina Derzhavina somewhat terse, though Pires’s utterly forlorn interpretation is compelling in an entirely different way.

Perahia’s ornamentation could fill the review on its own, for he’s happy to take risks, yet they never sound like risks, so firmly are they sewn into the musical cloth. Sample what he does with the Fifth Suite’s bustling Bourrée, glistening and playful. Or the Anglaise of Suite No 3, which is more unbuttoned in Perahia’s hands than in Angela Hewitt’s precisely imagined account. Preference will come down to personal taste.

With some artists, you have a sense that their personality comes across most strongly in the main structural movements of the French Suites – the opening allemandes, pivotal sarabandes and closing gigues. But one of the delights of this set is what Perahia does with the in-between movements. The Air in the Second Suite, for instance, which succeeds a Sarabande as full of pathos as any reading, twinkles with an easy playfulness; or the Loure of the Fifth, its dotted rhythms rendered with such poetry, Perahia’s ornamentation generous yet never overbearing. Or take the pair of Gavottes from the Fourth Suite, the first purposefully busy, the second a moto perpetuo of sinew and determination, but both having – that word again – a real sense of joy.

Perahia’s pacing is unerring throughout, and even if you tend to favour this movement slower, that one faster, the sense of narrative that he brings to these suites as a whole is utterly persuasive. Again, examples are manifold, but to take just one, try the Courante of the Sixth Suite, its streams of semiquavers and interplay between the hands a thing of delight. At the double bar, before the section repeat and before embarking on the second section, we get the slightest of hesitations, Perahia pausing just long enough to let the music breathe. It’s as if we exhale with him. All this would count for little were we not able to hear him in such beautifully immediate sound. So we should also pay tribute to Perahia’s longtime producer Andreas Neubronner, engineer Martin Nagorni and king among piano whisperers, technician Ulrich Gerhartz.

I’ve only had this recording for five days but I predict a long and happy future in its company. Harriet Smith (November 2016)

☆

Inventions. Sinfonias

Till Fellner pf

(ECM New Series)

While Bach may have conceived his Inventions and Sinfonias as teaching pieces, Till Fellner’s intelligent and characterful pianism consistently embraces the music behind the method book. Varied articulations and well conceived scaling of dynamics imbue the pianist’s natural propensity for generating singing lines with shapely expression. Cogent examples of this include the E major Invention’s subtle off-beat accentuations between the hands, the C major’s unpressured dialogues, the D minor’s incisive vitality, and the F major Sinfonia’s easy bounce and gentle spring. The often protracted D minor Sinfonia retains its melodic poignancy at Fellner’s headlong pace, although his tapered phrasing of the F minor Sinfonia’s theme grows predictable with each repetition.

Purists may also take issue with the tonal haze and mist resulting from Fellner’s liberal pedalling in the E major Sinfonia or, in the G major French Suite, the pianist’s soft-grained Allemande and Loure. However, the Sarabande’s simple eloquence plus the crisply pointed Bourrée and Gigue more than compensate. All told, the Inventions and Sinfonias in Fellner’s hands rank alongside the catalogue’s strongest piano versions (including Gould, Schiff, Koroliov, Hewitt and Peter Serkin), and benefit from ECM’s superior, state-of-the-art engineering. Jed Distler (September 2009)

☆

Organ Works, Vol 1

Masaaki Suzuki org

(BIS)

Of all the current doyens of modern Bach performance, Masaaki Suzuki knows no limits to his explorations. This is a dazzling recital (from a musician better known as a director-harpsichordist) discerningly assembled and held aloft by three great pillars: the ubiquitous Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV565; the Pièce d’orgue, BWV572, with Bach whisking the French 17th century from under its own nose; and, to conclude, the great Prelude and Fugue in E minor, BWV548 (the Wedge). If one’s reflexive default at the prospect of an organ recording – even an exquisitely curated Bach one – is one of dispassionate or nonchalant resistance, this recording is as likely to turn ears as any made.

Along the way, in a deftly balanced presentation of strikingly contrasting essays, Suzuki offers beautifully turned, reflective and buoyant readings of sui generis ‘concert’ works. The Pastorale, with its exquisite musette-like opening, whose subsequent C major movement trips along in a manner organists seem universally reluctant to pursue, is simply a pearl. Each of the four movements is sweetly devotional in nature, skilfully preparing the way for the highly distilled and contemplative variations on the chorale ‘O Gott, du frommer Gott’. The seasoned reflective qualities of Suzuki, heard to such memorable effect in his complete cantatas series, are reawakened in the stunningly voiced combinations of sounds from the Schnitger/Hinz in the Martinikerk in Groningen – one of Holland’s finest Baroque organs, restored to its former glory by Jürgen Ahrend during the 1970s and ’80s.

Unusual here, also, is how an emphatically non-organ-playing reviewer can effortlessly alight on the kinds of malleable Bachian conceits enjoyed habitually in the composer’s concertos, keyboard suites and vocal works. Great instrument aside, this is largely down to the judicious alchemy of Suzuki’s perception of how architecture and local colour can collide to mesmerising effect. The Fugue from the above-mentioned D minor is a case in point: the glistening parallel motion over the pedal at 3'20", often a bloated gesture, enticingly holds back to set up the rich-textured gravitas that follows. Inexorable momentum here is born of fervent authority, a virtuosity of combined effects without gratuitous excess.

The Canonic Variations on ‘Vom Himmel hoch’, written late in Bach’s life as a condition of membership of Lorenz Mitzler’s Corresponding Society of the Musical Sciences (hence the work’s proliferation of contrapuntal wizardry), can often leave the listener cold. Perhaps not surprisingly, Stravinsky was beguiled by the possibility of its intertwining lines in his inventive homage of 1956, with its supra-polyphonic interpolations. Suzuki’s performance will persuade you that Bach’s unsurpassed technique never obfuscates the essence of the chorale; its Christmas provenance is fragrantly atmospheric. The close, with its ingeniously compressed lines and the composer’s outrageous sign-off, literally spelling his name (B is B flat and H is B natural), is celebrated in some style by Suzuki.

But it’s the gripping drama and involvement in the large-scale works that remind one of Karl Richter in his most durable organ-playing legacy on Archiv from the 1960s (funnily enough, until recently, only available in Japan). Richter’s captivating direction and intensity, complete with an almost hypnotic abandon, is a touch more measured in Suzuki’s hands but no less effectively communicated.

The E minor Prelude and Fugue is the greatest tour de force here, and arguably Bach’s most ambitious single creation on the organ. Truly symphonic in grandeur, the work is harnessed impressively by this exceptionally experienced Bachian. Granite-like blocks of intensely chiselled harmonic progressions starting at 2'38" and building to the last at 5'48" are studiously laid down, as if for posterity, and yet there’s an underlying immediacy and restlessness in Suzuki’s rhetoric which leads to thrillingly choppy waters in the Fugue. Only Samuil Feinberg’s arrangement on the piano has lifted this piece completely out of its safe organ istic sphere – but I think it now has a partner in grandeur, flair and emotional risk. And it’s on the organ. Jonathan Freeman-Attwood (October 2015)

☆

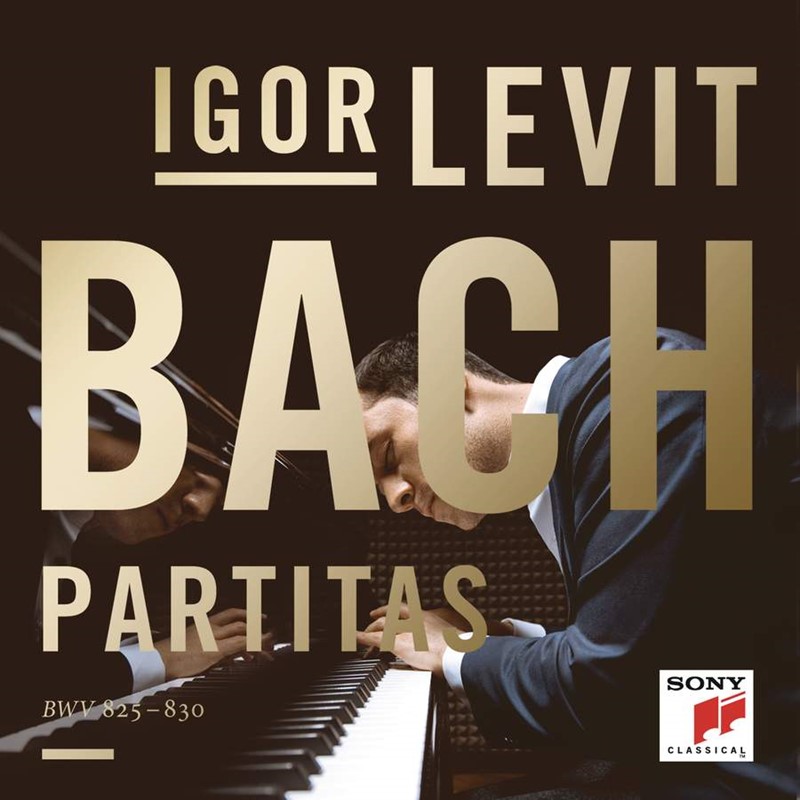

Partitas

Igor Levit pf

(Sony Classical)

‘When in trouble, play Bach’ – wise advice from Edwin Fischer to a pupil. He was making an observation to a fellow performer about Bach’s restorative and reorienting powers; no doubt, but perhaps alerting all of us to the inspiring breath we can draw from the fertility and humanity of a composer whose imagination and ‘habit of perfection’ (John Eliot Gardiner’s phrase) drove him to discover in music just about everything. For the keyboard player, an engagement with Bach is a constant from childhood, and it becomes essential to daily life. For Beethoven, for Mozart in his maturity and for Chopin, it was the same. ‘Practise some Bach for me,’ Chopin used to say to his departing pupils as they went through the door. Yet no music is more demanding to realise in sound, nor quicker to reveal inadequacies of perception.

Which brings me to Igor Levit – and not a moment too soon, you may think. The distinction of this set of the Partitas, following his Sony debut recording of the last five Beethoven sonatas (11/13), will establish him in the minds of many, I’m sure, as a major artist. He played those sonatas as though he had lived with late Beethoven a long time and had perceived and understood everything. His versions of the six Bach Partitas show a comparable address and maturity. Above all, they are fresh and joyous.

How demanding they are. On the title-page of the collected edition of 1731, brought out as his Op 1 and a self-publishing job, Bach said he had composed them ‘for music lovers, to delight their senses’. They soon made a great noise in the musical world but earned him, too, a reputation for their technical difficulty: as if, as a contemporary put it, the composer had expected ‘what he alone could do on the keyboard’. An early player of them, said to have been accomplished, described them as ‘making me seem like a beginner each time’.

Complex music – but not complicated. Levit’s achievement is to miss nothing of their scope and variety as compositions while conveying what it is that makes each one a unity, not an anthology, demanding to be performed complete. Where other practitioners offer regular accents and a perhaps over-cautious traversal, tethered to the notes, Levit never fails to project a commanding overview – an aerial perspective, almost – in addition to the detail of phrasing and articulations and the nooks and crannies of melodic lines. Only the most gifted interpreters manage both. It energises his performances and makes them seem to inhabit a state of grace. And it contributes to our enjoyment in another way, drawing us on as we listen and keeping us curious as to what lies around the next corner. A first impression might be of quicker tempi than usual and of a fleetness that challenges us to keep up. Yet one quickly registers that nothing, in fact, is rushed or driven too hard – not a phrase or a paragraph, nor even (most important) the execution of an ornament.

I like very much Levit’s ornaments and embellishments in general. They are always a living feature of the line, arising from within, not stuck on from without. In addition they show awareness of performance practice and what may be appropriate in each instance, with decoration added to ‘second times’ discreetly and with an air of spontaneity, and never to excess. Levit has a sure judgment of when to leave well alone, as CPE Bach advised when discussing this aspect of his father’s music. The majestic Sarabande of No 1 in B flat (disc 1, tr 4) gets a minimum of graces in its repeats – barely noticeable indeed. But there needs to be some if ‘second time through’ is to have any sense; otherwise why do it?

The playing of the Gigues in the Partitas – and the final Capriccio in No 2 in C minor – invite the performer’s virtuosity as a welcome guest to the feast. Levit doesn’t disappoint. Bach developed these movements to make thrilling conclusions, just as he had made the opening of each work something imposing and unexpected. That was possibly his most original contribution to the suite of his time: there’s a Praeludium in No 1, a three-part Sinfonia in No 2, a French Overture in No 4 (the D major), a Praeambulum in No 5 and a grand Toccata and Fugue in No 6 (E minor). They help to make each partita announce itself as something ambitious and a unity, not just a succession of dances. With Levit, if you start at the beginning, you go on to the end; no question. Bach mediates between the French and the Italian styles in the course of the six works, and Levit doesn’t miss a trick. Finally, let me praise his cantabile playing (a singing style), which Bach extolled to his students as a constant aim.

Harpsichord or piano? Forget it. Or rather, let us have both. If on the piano, however, which isn’t a second-best, I incline to those exponents who are not apologetic about their instrument and at the same time show awareness, relish even, of what the best harpsichordists have achieved, from Gustav Leonhardt to Andreas Staier (I mention two exceptional players who have made complete sets). As to other pianists, I would cite Richard Goode, on a par with Murray Perahia; maybe András Schiff as well. Levit’s version has added to the discography of this inexhaustible music with distinction and I believe it will run and run. There’s nothing about him in the booklet – as if to say, it’s not about me, the music is enough. But if you haven’t come across him before I can report that he’s of Russian-German descent (shades of Sviatoslav Richter) and is 27 this year. I wonder what he’ll do next. Stephen Plaistow (October 2014)

☆

Partitas, BWV825–30

Trevor Pinnock hpd

(Hänssler Classic)

Hanssler’s eclectic approach to its ongoing complete Bach series is either one of its greatest strengths or one of its strongest irritations, depending on how you look at it. Is offering the English Suites on the piano and the Partitas on the harpsichord a commendably broad-church approach or just haphazard? The massive Bachakademie edition (of which this is Volume 115) is not a project noticeably concerned with period instruments, yet here they have persuaded Trevor Pinnock, founder of one of the world’s first and finest baroque orchestras, the English Concert, to return to the recording studio as a solo harpsichordist for the first time in many years.

Well bravo to them. The evidence of these discs is that Pinnock’s absence from the new release lists has been far too long. From the opening bars of the First Partita’s leisurely Praeludium, it is clear that this is a master harpsichordist, a player whose seemingly effortless command of his instrument allows him to express his innate musicianship without any need for overstatement or gratuitous point-making. There is nothing laboured or studied about his performances of these demanding works; his faultless finger technique allows him not only to step with confidence through a virtuoso minefield such as the Gigue of the Fifth Suite (his are the tightest trills I have heard), but perhaps, more important, to make a gently flowing legato the starting-point of his interpretation. It is an approach that could run the risk of being boring were it not that Pinnock’s ability to place every note precisely and sensitively – helped by an instrument (or is it the recording?) which takes the edge off each note’s attack – makes it come across as wonderfully natural and unaffected. Bach, after all, can do the rest.

Tempos, too, have a sense of rightness about them; the slightly excitable Pinnock of old has now become a fine and subtle judge of forward motion, shown to greatest advantage perhaps in his perfect reading of the giant Allemande from the Fourth Partita, a piece so hard to steer between the hasty and the leaden. And he can sparkle when he needs to; try out the fizzing Corrente of the Sixth Partita.

These are performances of enormous distinction, then, and it is a pleasure to welcome Pinnock back after such an absence. Let’s hope that he will soon catch up lost ground and record more of his instrument’s mainstream repertoire. Lindsay Kemp (August 2000)

☆

Toccata in C minor, etc

Martha Argerich pf

(DG)

The reissue of Martha Argerich’s recordings, their reappearance in this or that format, testifies to the unique and enduring nature of her magisterial temperament and musicianship. This Bach recital, first issued in 1980, reissued in DG’s Galleria series and partially celebrated (the C minor Partita) in Philips’s Great Pianists of the Twentieth Century, is now revived on DG’s The Originals. Admirers will of course have heard Argerich in the Second Partita, on the wing, so to speak, in a superlative live performance dating from 1978-79 (and with the Bouree from the Second English Suite for an encore) on EMI. Yet even they will surely admit that these slightly later studio recordings carry an extraordinary authority and panache.Argerich’s attack in the C minor Toccata could hardly be bolder or more incisive, a classic instance of virtuosity all the more clear and potent for being so firmly but never rigidly controlled. Here, as elsewhere, her discipline is no less remarkable than her unflagging brio and relish of Bach’s glory. Again, in the Second Partita, her playing is quite without those excesses or mannerisms that too often pass for authenticity, and at 2'14'' in the Andante immediately following the Sinfonie she is expressive yet clear and precise, her following Allegro a marvel of high-speed yet always musical bravura. True, some may question her way with the Courante from the Second English Suite, finding it hard-driven, even overbearing, yet Argerich’s eloquence in the following sublime Sarabande creates its own hypnotic authority. Her final Gigue is a triumph of irrepressible vitality yet, throughout, you are reminded of the comprehensiveness of Argerich’s Bach, the way his alternations of robust and interior musical thinking are so tellingly and vividly characterised.It only remains to add that the dynamic range of these towering, intensely musical performances has been excellently captured by DG. Bryce Morrison (Awards issue 2000)

☆

Toccatas

Angela Hewitt pf

(Hyperion)

As Angela Hewitt tells us in her exemplary accompanying essay‚ Bach’s Toccatas were inspired by Buxtehude’s ‘stylus fantasticus – a very unrestrained and free way of composing‚ using dramatic and extravagant rhetorical gestures’. For Wanda Landowska‚ they seemed initially ‘incoherent and disparate’ and it takes an exceptional artist to make such wonders both stand out and unite. Yet Angela Hewitt – always responsive to such a teasing mix of discipline and wildness – presents even the most audacious surprises (the close to the G major‚ the chromatic grandeur in the Adagio from the F sharp minor‚ etc) with a superb and unfaltering sense of balance and perspective. Time and again she shows us that it is possible to be personal and characterful without resorting to selfserving and distorting idiosyncrasy. Everything is delightfully devoid of pedantry or overemphasis; few pianists have worn their enviable expertise in Bach more lightly. How scrupulously she observes Bach’s moderato qualification in the C minor Toccata’s Allegro fugue‚ how delicate and precise her way with the same fugue’s return. Again‚ in the F sharp minor Toccata everything is meticulously graded‚ and in the dazzling D major Toccata‚ which so fittingly closes her programme‚ not even Bach’s most ebullient virtuosity can induce her to rush; everything emerges with a clarity that never excludes expressive beauty. Commenting that it is impossible to know the precise chronology of the Toccatas‚ Hewitt plays what she calls ‘an arbitrary sequence’‚ modestly aiming for a ‘satisfactory recital’. As a necessary corollary‚ her performances could hardly be more stylish or impeccable‚ more vital or refined; and‚ as a crowning touch‚ Hyperion’s sound is superb. Bryce Morrison (October 2002)

☆

The Well-tempered Clavier

Edwin Fischer pf

(Naxos)

Edwin Fischer’s 1933-36 HMV set of Bach’s 48 was the first recording by a pianist of the set, and it remains the finest of all. Fischer might well have agreed with Andras Schiff that Bach is the ‘most romantic of all composers’, for his superfine musicianship seems to live and breathe in another world, ether or ambience. His sonority is as ravishing as it is apt, never beautiful for its own sake, and graced with a pedal technique so subtle that it results in a light and shade, a subdued sparkle or pointed sense of repartee that eludes lesser artists. Again, no matter what complexity Bach throws at him, Fischer resolves it with a disarming poise and limpidity, qualities as natural as they are profound.

All this is a far cry from, say, Glenn Gould’s egotism in the 48, or the sort of performances that can make genius a pejorative term. Fischer – a blessedly naive artist who told his students to forget ‘the material, working world and be on intimate terms with trees, clouds and winds’ – showed a deep humility before great art, making the singling out of one or another of his performances an impertinence. Impossible, however, not to mention in passing his ethereal start to the set (that light, bouncing staccato above a singing bass-line in No 1), or the disconsolate, phantom yet ordered voice he achieves in No 4. The contrapuntal flow of No 7 – initially grand, then reflective and finally free-wheeling – is realised to perfection, and what a virtuoso play of the elements he recreates in No 15!

Turning to Book 2, you could hardly imagine a more seraphic utterance in No 3, later contrasted with the most skittish allegro reply. The list goes on indefinitely, dissolving the supposed barriers between one form of music and another: ‘baroque’, ‘classical’, ‘romantic’, even ‘impressionist’, become terms of convenience rather than accuracy once you have heard Fischer’s Bach. He did, indeed, possess a touch with ‘the strength and softness of a lion’s velvet paw’, and I know of few recordings from which today’s generation of pianists could learn so much; could absorb by osmosis, so to speak, his way of transforming a supposedly learned tome into a fountain of limitless magic and resource.

Here, then, is Fischer at his most sublimely poised and unruffled, offered at Naxos’s bargain price in beautifully restored sound. Bryce Morrison (May 2001)

☆

The Well-tempered Clavier

Ewa Pobłocka pf

(NIFC)

Ewa Pobłocka’s name first came to my attention back in 1980, when she tied for fifth place in that year’s Warsaw International Chopin Competition, and Deutsche Grammophon issued a selection of her performances from that event on a bygone LP. Since then she has pursued a steady and successful career as both soloist and chamber musician, with a sizeable discography to her credit. Gramophone readers may be familiar with her acclaimed performance of Panufnik’s Piano Concerto with the composer conducting (RCA, 5/92), and a terrific recital of Polish songs where the pianist supports the mezzo-soprano Ewa Podles´ (CD Accord, 10/99). I enthusiastically endorsed a live archival 1984 recording of Chopin’s E minor Concerto in these pages last April. A good number of Pobłocka’s recordings, however, are either out of print or difficult to source. I hope that will not become the fate of this remarkable release.

Her Bach has everything going for it: pianistic resourcefulness, keen polyphonic acumen, impeccable taste and an ability to imbue each Prelude and Fugue with a distinct point of view borne out of musical considerations. You notice this from the start. Her C major Prelude unassumingly unfolds at a moderate pace, resonating less like a piano than a murmuring organ, while the C major Fugue sounds like a madrigal featuring four distinct yet unified voices with prodigious breath control. By contrast, the C minor Prelude and Fugue stands out for Pobłocka’s hard-hitting detached articulation. The C sharp major Prelude’s arching phrases remind me of Myra Hess’s similarly unpressured vintage recording, and her fluidly lyrical approach to the C sharp minor Fugue highlights the music’s harmonic poignancy yet appreciably minimises its austere reputation.

Note, too, Pobłocka’s swaggering D major Fugue and how each entrance of the D minor Fugue’s exposition is consistently phrased, down to the slight tapering of the trill. Listen to the E flat minor Prelude and try to focus exclusively on Pobłocka’s careful dynamic calibrations in the accompaniment: what understated sustaining power and legato mastery! By contrast, the F major Prelude and Fugue amounts to a masterclass in how to imbue détaché articulation with the utmost colour and character, not to mention trills that are impeccably precise yet never mechanical-sounding. Her E minor Fugue keeps the motoric momentum in the foreground without losing melodic direction, while her intriguing interplay of voices in the F minor Prelude retains textural distinctiveness and cogency throughout. My comments about the C major Fugue likewise apply to the F sharp minor Fugue’s vocally informed trajectory.

Pobłocka uncommonly downplays the G minor Prelude’s long trills (as did Alexandra Papastefanou in her recent recording – First Hand, 10/18) and emphasises the A major Fugue’s dizzying cross rhythms while giving an extra kick to the subject’s first note for good measure. Listen to the gorgeous conversational quality in the F sharp major Prelude, as if Pobłocka’s hands were a pair of chamber music partners. I’ve rarely heard a comparably upbeat and joyous A flat Prelude, or an A flat Fugue so organically tapered. The G sharp minor Prelude is a particularly inspired example of Pobłocka’s controlled freedom and imaginative voicings. She holds interest in the long and difficult-to-sustain A minor Fugue by terracing the dynamics and incorporating myriad alternations of touch and timbre. And Pobłocka’s soaring alla breve reading of the B minor Prelude differs from the measured tread of, say Daniel Barenboim or Edward Aldwell. Although she takes her time over the B flat minor and B minor Fugues, Pobłocka’s strong inner rhythm and subtle organisation of dynamics keep the music alive in every bar.

One can take issue with occasional tenutos that verge on mannerism (Pobłocka’s phrasing of the E flat Prelude’s introduction), or how she glibly trots out the F major Prelude. But such quibbles are inconsequential in face of this pianist’s heartfelt musicality, enhanced by attractively full-bodied sound and a beautifully regulated Shigeru Kawai SK EX concert grand at her disposal. Wary as I am of superlatives, I can claim without hesitation that Ewa Pobłocka’s Well-Tempered Clavier Book 1 encompasses some of the greatest and most fulfilling Bach pianism on record. I look forward to Book 2. Jed Distler (March 2019)

☆

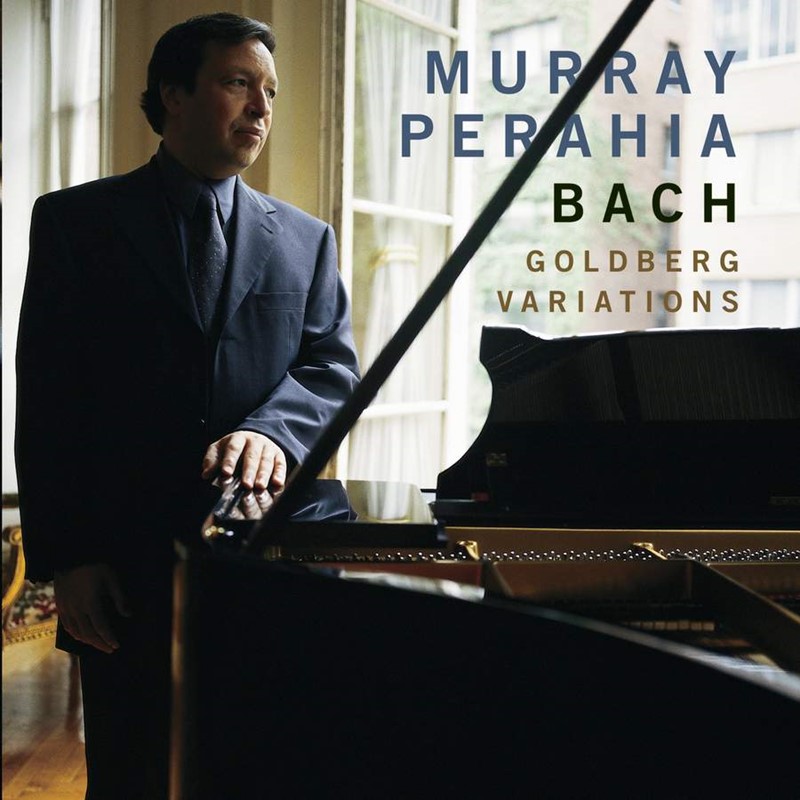

Goldberg Variations

Murray Perahia pf

(Sony Classical)

The roll call of Goldbergs on disc amounts almost to one first-class version per variation. I cannot think that there’s a single recording (and by now I must have heard at least 30) that doesn’t identify some minor detail unnoticed by others. My last Gramophone review celebrated Angela Hewitt’s sense of colour, and the passing months have done little to dim the appeal of her fine Hyperion recording. Now Murray Perahia enters the fray with a version that isn’t just colourful, or virtuosic, or thorough in terms of repeats, but profoundly moving as well. Here one senses that what is being played isn’t so much ‘Bach’ as an inevitable musical sequence with a life of its own, music where the themes, harmonies and contrapuntal strands await a mind strong enough to connect them. This Perahia does with sovereign command, and his perceptive programme notes help illuminate the complexion of his thinking.

Rosalyn Tureck was the first recorded Goldbergian to take the structural route and her EMI/Philips set remains among the most cogent of older alternatives. And while Glenn Gould achieves formidable levels of concentration (especially in the second of his two commercial recordings for Sony), his gargantuan personality – utterly absorbing though it is – does occasionally intrude. Perahia brooks neither distraction nor unwanted mannerism. He invests the Goldbergs with the sort of humbling gravitas that Schnabel brings to, say, Schubert’s B flat Sonata. Yes, there are fine-tipped details and prominent emphases (sample the wildly accentuated bass-line in Variation 8), but the way themes are traced and followed through suggests a performance where the shape of a phrase is dictated mostly by its place in the larger scheme of things.

The opening Aria is crystalline, lively in tone and with a distinctly singing bass-line. The first repeat is rather softer, whereas the first repeat of the first variation incorporates various added ornaments, a trend that registers time and again through the course of the performance. Middle voices are brought to the fore in Variation 3 and where, in Variation 4, Hewitt opens boldly and softens for the first repeat, Perahia reverses the process. Variation 7 is crisp and tripping, 16 opens to firmly brushed arpeggios, and I loved Perahia’s pianistic gambolling in the snakes and ladders of Variation 23. Hewitt is amazingly skilful in the contrary motions of 21 but Perahia keeps a firmer hold on the principal theme and in Variation 25 his classic, sculpted lines conjure a level of purity reminiscent of Lipatti (in Bach generally, that is – not the Goldbergs in particular, which Lipatti never recorded).

Perahia never strikes a brittle note and yet his control and projection of rhythm are impeccable. He can trace the most exquisite cantabile, even while attending to salient counterpoint, and although clear voicing is a consistent attribute of his performance, so is flexibility. He makes points without labouring them, which is not to deny either the brilliance or the character of his playing. Like Hewitt, he surpasses himself. It’s just that in his case the act of surpassing takes him that little bit further. A quite wonderful CD. Rob Cowan (December 2000)

☆

Goldberg Variations

Pierre Hantaï hpd

(Naive, 1994 rec)

One of the first things to strike the listener in this new recording of Bach's Goldberg Variations is the fine quality of Bruce Kennedy's copy of an early eighteenth-century instrument by the Berlin craftsman, Michael Mietke. Its character, furthermore, is admirably captured by the effectively resonant recorded sound, a shade too close for some ears, perhaps, but not for me.

The soloist, Pierre Hantai, is a member of a talented French musical family who studied first with Arthur Haas, then with Gustav Leonhardt. His approach to the Goldbergs is tremendously spirited and energetic but also disciplined. What I like most of all about this playing, though, is that Hantai clearly finds the music great fun to perform. Some players have been too inclined to make heavy weather over this piece and I have sometimes been driven to despair by the seriousness with which the wonderfully unbuttoned Quodlibet (Var 30) is despatched. Hantai makes each and every one of the canons a piece of entertainment while in no sense glossing over Bach's consummate formal mastery. Other movements, such as Var 7 (gigue) and Var 11, effervesce with energy and good humour. Yes, this is certainly the spirit which I like to prevail in my Goldberg Variations. But, as I say, Hantai is careful to avoid anything in the nature of superficiality. Not for a moment is the listener given the impression that his view of the music is merely skin deep. Indeed, there is a marked concentration of thought in canons such as that at the fourth interval (Var 12). Elsewhere, I found Hantai's feeling for the fantasy and poetry of Bach's music effective and well placed (such as in Var 13).

Little more need be said except that Hantai has taken note of Bach's autograph corrections to the text published in Nuremberg in 1741 or 1742 by Balthasar Schmid. Invigorating, virtuosic playing of this kind deserves to win friends, and my recommendation is that, whether or not you already possess one or more recordings of the Goldbergs, you make a firm commitment to add this one to your library. The Ouverture (Var 16), the Quodlibet and much else here have an irresistible esprit, a happy conjunction of heart and mind. Another triumph for an enterprising label. Nicholas Anderson (April 1994)

☆

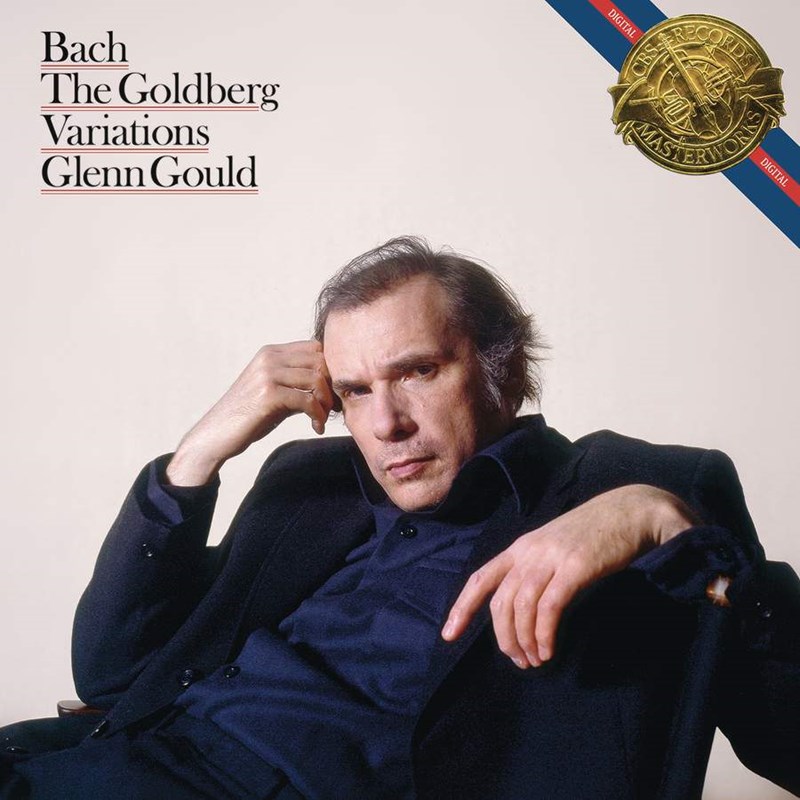

Goldberg Variations

Glenn Gould pf

(Sony, 1981 rec)

This truly astonishing performance was recorded in 1981, 26 years after Gould's legendary 1955 disc. Gould was not in the habit of re-recording but a growing unease with that earlier performance made him turn once again to a timeless masterpiece and try, via a radically altered outlook, for a more definitive account. By his own admission he had, during those intervening years, discovered 'slowness' or a meditative quality far removed from flashing fingers and pianistic glory. And it is this 'autumnal repose' that adds such a deeply imaginative dimension to Gould's unimpeded clarity and pin-point definition. The Aria is now mesmerically slow. The tremulous confidences of Variation 13 in the 1955 performance give way to something more forthright, more trenchantly and determinedly voiced, while Var. 19's previously light and dancing measures are humorously slow and precise. Variation 21 is painted in the boldest of oils, so to speak, and most importantly of all, Landowska's 'black pearl' (Var. 25) is far less romantically susceptible than before, has an almost confrontational assurance. The Aria's return, too, is overwhelming in its profound sense of solace and resolution.

Personally, I wouldn't want to be without either of Gould's recordings yet I have to say that the second is surely the finest. The recording is superb and how remarkable that what are arguably Gould's two greatest records should be his first and his last.' Bryce Morrison (August 1993)

☆

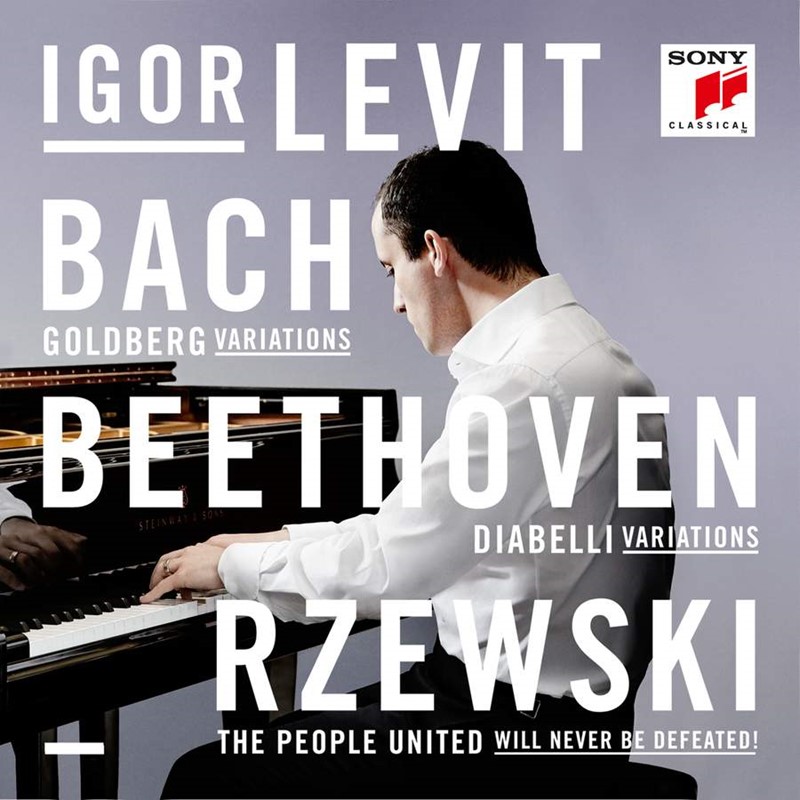

Goldberg Variations

Igor Levit pf

(Sony Classical)

Igor Levit’s late Beethoven sonatas (11/13) and Bach Partitas (10/14) on Sony Classical have already made bold declarations of his pianistic and artistic prowess. Now he confirms his appetite for the big entrance with three monuments to variation form, each rooted in its own century, yet all united by the harnessing of maximum variety, maximum discipline.

Levit will be stuck for some years to come with the epithets ‘young’ and ‘Russian-born, German-trained/domiciled’. But the instant he touches the piano such information becomes irrelevant. Certainly he can muster all the athleticism, velocity and finesse of a competition winner ready to burst on to the international scene. But like the rarest of that breed – a Perahia, say – his playing already has a far-seeing quality that raises him to the status of the thinking virtuoso. There is, if you care to rationalise, a Russian depth of sound and eloquence of phrasing, tempered by Germanic intellectual grasp. There is also a sense of exulting in technical prowess and energy. But not once in the course of these three themes and 99 variations did I feel that such qualities were being self-consciously underlined. Levit’s musical personality is as integrated and mature as his technique. And both of these are placed at the service of the music’s glory rather than his own.

Levit’s Goldberg Variations range themselves more naturally alongside the patrician intelligence of a Perahia than with the sui generis extremes of a Glenn Gould. At times Perahia’s imagination in repeats arguably betokens a fraction more wisdom. But such fine nuances only emerge in the dutiful process of comparison, rather than in the wholly absorbing experience of Levit traversing another musical peak. Top-notch recording quality, too. If a finer piano recording comes my way this year I shall be delighted, but frankly also astonished. David Fanning (November 2015)

☆

Italian Concerto. Partitas, etc

Walter Gieseking pf

Naxos

A famous response to Gieseking’s playing as being “like Monet in Giverny” was made with reference to his legendary Debussy performances. Yet although Gieseking’s phenomenal aural sensitivity earned him a unique reputation in French piano music, his repertoire was all-embracing. This included the concertos of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov and, in 1930, he gave a New York recital entirely devoted to contemporary music. All the more reason then to celebrate Naxos’s release of Gieseking’s Bach and Beethoven in recordings dating from 1931-40, made when this unique artist was at the height of his career.

Here you will search in vain for the sort of muddles or confusions that would sometimes plague his performances (evidence of his proud boast that he did little practice). His Bach has a peerless lightness, grace and natural beauty, the reverse of Teutonic earnestness and heaviness. The Andante from the Italian Concerto, a tirelessly ornamented aria, is given with an enviable poise and lucidity while in the Gigue from the First Partita his playing is, again, the opposite of a more familiar cold-hearted virtuosity, making you regret that there are only excerpts from this exquisite masterpiece. In the Fifth Partita (given complete) Gieseking shows the most subtle virtuosity and is no less convincing in the Sixth Partita’s more strenuous and concentrated demands.

Beethoven’s Tempest Sonata is given without first- or last-movement repeats and is taken, in those outer movements, at such a pace that there are occasional dangers that the music’s character is whisked out of existence (the finale is, after all, marked allegretto). For encores there are Beethoven’s E flat Bagatelle from Op 33 and the Bach-Hess Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring where Gieseking plays with admirable restraint while not quite equalling Dame Myra’s own inimitable poise. Bryce Morrison (January 2010)

☆

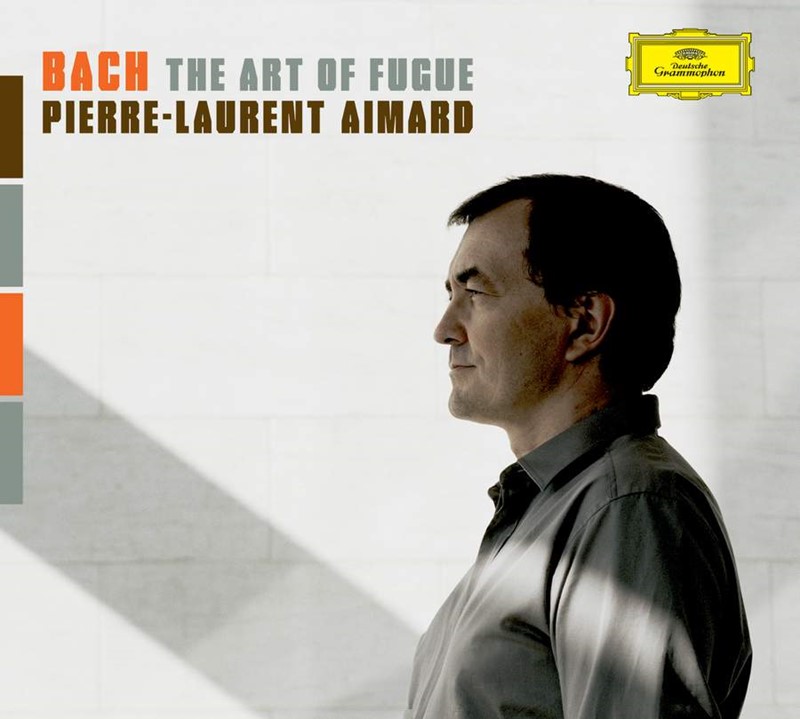

The Art of Fugue

Pierre-Laurent Aimard pf

(DG)

This is Bach-playing to listen to every day, fresh, spry and well modulated. If spirituality is to be found in The Art of Fugue, Aimard seems to say, it will not be through slow tempi, dynamic extremes or the quasi-religious trappings arrayed by the likes of Sokolov, Kocsis, Koroliov and Nikolaieva. The tripping, French swagger of Contrapuncti 2 and 6 and the smart Italian cut of No 9 fit neatly under the fingers. Freedom is found within the interplay of voices rather than any fancy phrasing: in fact the mirror fugues and canons are so unfussily done that you’d never guess without a score to hand how much a single musician can look and sound like Mr Messy while playing them.

This is not to imply dryness or inflexibility on Aimard’s part. He follows Tovey in finding No 3 to be “one of Bach’s most beautiful pieces of quiet chromatic slow music”, after which the extraordinary cadences of No 4 (actually the final completed movement) are necessarily pedalled and clipped, even chirpy: the envoi of a true Kapellmeister. The great unfinished fugue is especially fascinating, gradually accumulating kinesis until the surge of B-A-C-H pulls us towards its unattained apotheosis with the force of the Severn Bore. Applied with more plain-spoken authority, such emphatic strength of wrist and will rather chews up the Tenth’s preludial bars and the expansive, chorale-fantasia conclusion of the Fifth, though with equal force one senses that, in this case, they had to be so. Perhaps no pianist since Charles Rosen has so persuasively demonstrated that this contrapuntal encyclopedia is to be heard as well as read. Peter Quantrill (March 2008)

☆

Keyboard Works

Víkingur Ólafsson

(DG)

Not exactly being a fan of Philip Glass’s music, this is the first time I’ve encountered Víkingur Ólafsson on disc, though I was very taken with his Bach in concert last year. That impression is deepened by this disc: here is an artist who palpably adores and reveres JSB in equal measure, and makes sense of a programme that could have sounded bitty – 35 tracks, with the biggest work being the youthful Aria variata (alla maniera italiana).

In terms of pianistic lineage, Ólafsson combines the fantasy of Maria João Pires and Martha Argerich with the contrapuntal élan of Piotr Anderszewski. But he is very much his own man, mixing original Bach with transcriptions that range from Stradal, Busoni and Rachmaninov via Kempff to the present day, with Ólafsson’s own rethinking of the luscious aria from the solo alto Cantata No 54, ‘Widerstehe doch der Sünde’, in which he channels the great transcribers of old, using left-hand octaves to give it a grounded feeling, and choosing a measured tempo more akin to Alfred Deller than Andreas Scholl.

Ólafsson’s notes tell of his discovery of Bach pianists as different as Edwin Fischer, Rosalyn Tureck, Dinu Lipatti, Glenn Gould and Martha Argerich. From this, he has found his own way with Bach – highly individual but never mannered. His account of Kempff’s transcription of the chorale prelude Nun freut euch is less anchored by the chorale tune itself and more flighty in effect than Kempff’s own performances (Eloquence). I like the way that Ólafsson alternates original Bach with the transcriptions, so that Stradal’s take on the middle movement of Bach’s Fourth Organ Sonata (given here with generous use of sustaining pedal to create a poetic ambience) is followed by a refreshingly airborne account of the D major Prelude from Book 1 of The Well-Tempered Clavier, while its Fugue melds clarity with nobility. After this comes the Busoni version of another chorale prelude, Nun komm der Heiden Heiland, which unfolds more naturally than in Demidenko’s hands (Hyperion). We then get another dash of cold water in the C minor Prelude and Fugue from Book 1. The Prelude is judged to perfection, combining energy and brilliance, the Fugue a model of crisp detail.

And so it continues: almost as if Ólafsson is offering different angles on the statue of Bach that he keeps by his piano – one that ‘looks like wisdom incarnate, stern-faced and majestic in its wig’. He brings considerable character to the theme of the Aria variata, tending to choose faster tempos than Angela Hewitt (Hyperion, 10/04), to thrilling effect in Variations 2, 7 and 9, while Var 6 has a limpid beauty. Even an outwardly simple piece such as the A major Invention, BWV783, is full of interest, the energy infectiously joyous, the trills razor-sharp.

Other highlights include the Bach/Rachamninov Gavotte from the E major Violin Partita, which here has an engaging nonchalance, and the Siloti reworking of the E minor Prelude from Book 1 of the WTC, a model of restraint in which Ólafsson allows the music’s beauty to shine through. If the first movement of the Harpsichord Concerto in D minor (Bach’s arrangement of Marcello’s D minor Oboe Concerto) is almost too punchy in its ebullience, the famous Adagio is suitably haloed and the finale fizzes. He ends his journey with the A minor Fantasia and Fugue, BWV904, which again is unerring in its sense of build, the closing bars of the Fugue making a fittingly grandiose conclusion to the disc.

DG’s engineers have done this remarkable musician proud. I can’t wait to hear what he does next. Harriet Smith

Adaugă un comentariu

© 2024 Created by altmarius.

Oferit de

![]()

Embleme | Raportare eroare | Termeni de utilizare a serviciilor

Pentru a putea adăuga comentarii trebuie să fii membru al altmarius !

Alătură-te reţelei altmarius