cultură şi spiritualitate

The Iraq War has damned the former British Prime Minister in the eyes of many. But his support for regime change was widely shared at the time.

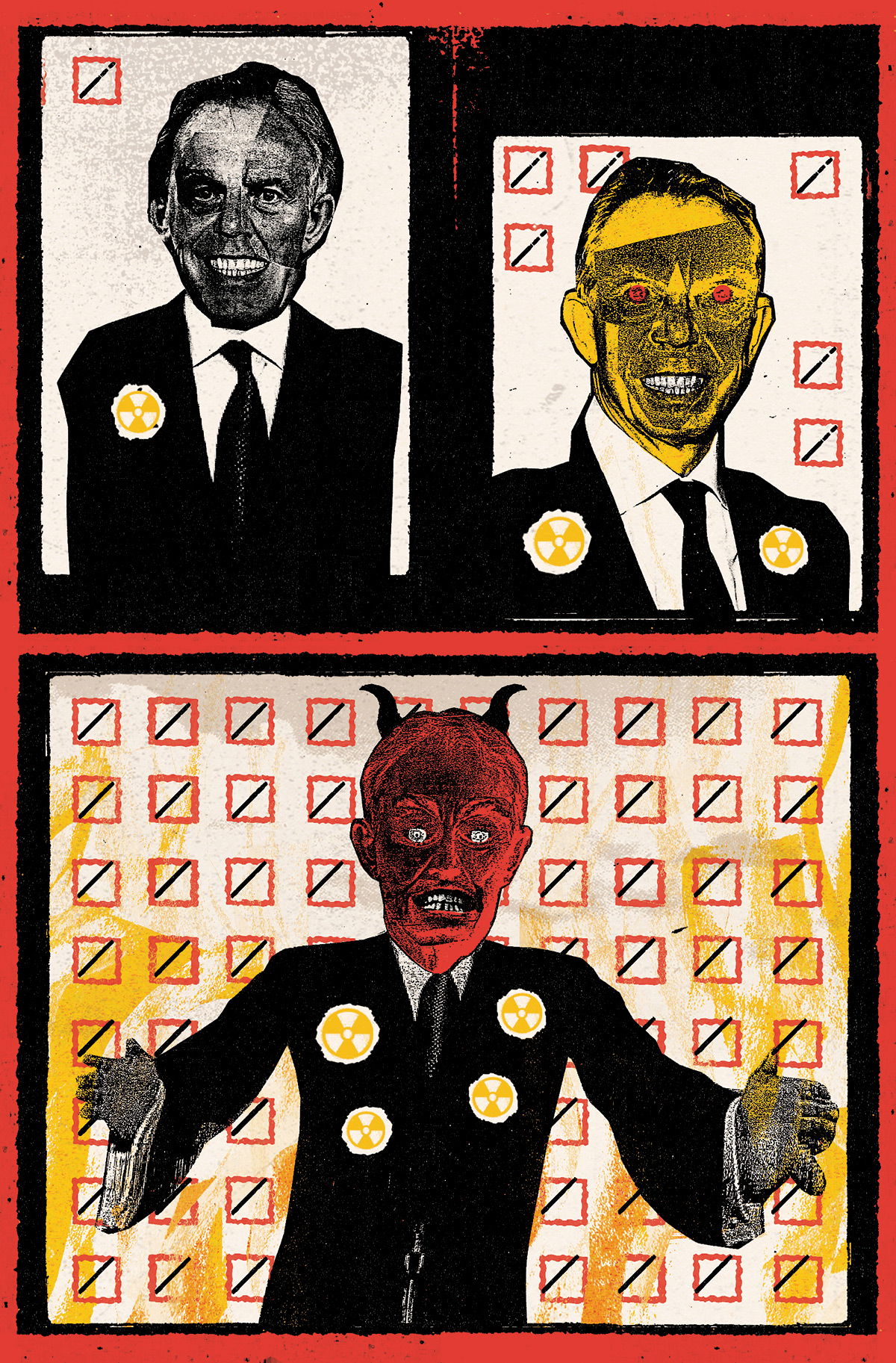

Illustration by Ben Jones.

Illustration by Ben Jones.

In 2003 Britain joined a US-led coalition to invade Iraq. In folk memory, it has become ‘Blair’s War’, driven by his delusions, his bad faith and his close alignment with a US president. But it was not just Blair’s War. It was Britain’s. The will to war was wider than many like to recall. As long as Blair is the scapegoat, Britons will fail to confront questions of security and power. It could all happen again.

‘Operation Telic’ was a defeat: Britain’s first since the withdrawal from Aden in 1967, its largest-scale combat since Korea, biggest disappointment since Suez and most polarising since the Boer War. It was meant to be a lightning strike on the regime of Saddam Hussein, which would give rise to a constitutional government and create a benign domino effect in the Middle East. It cost the UK £9 billion, degenerating into an attritional counterinsurgency campaign, with troops outnumbered and at times outgunned. Hundreds more troops died and thousands more were wounded than envisaged.

War of warning

The war was meant to warn others against acquiring Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD). But Iraq had already disarmed. By destroying a government that had abandoned the pursuit of a nuclear deterrent, the coalition demonstrated the logic of holding on to the bomb: North Korea’s regime has said it will not go the way of Saddam. The war was supposed to liberate Iraq, but the fall of Saddam unleashed sectarian bloodshed and civil war that opened up a new front for Al Qaeda, energised Islamic State and helped begin the region’s descent into conflict along multiple axes: Sunni-Shia, Saudi-Iranian. It led to a Shia ascendancy in Baghdad, which carried out atrocities. Though supposed to reignite the Arab-Israeli peace process, a resolution and a Palestinian state are as remote as ever.

By paying the ‘blood price’, the campaign was also supposed to buy British influence over the US. But UK casualties did not persuade Washington to do what London wanted: over the purges of the civil service and army in Iraq, or beyond that, on climate change, the International Criminal Court, or industrial subsidies. Even during the campaign, Britain was marginalised. Within a few years, the US had reconciled with France, which had led opposition to the war.

Even the withdrawal was a disappointment. Britain’s MI6 station chief negotiated a deal with a leader of the Iranian-backed Jaysh al-Mahdi (JAM), which was besieging British bases. The militia agreed to stop targeting Britons in exchange for the release of detainees from British custody. UK troops were permitted to withdraw from Basra Palace to the airport, a withdrawal the militia policed en route.

Critics recall a silver-tongued premier hoodwinking the public, falsifying evidence, grovelling to a superpower, foisting a disastrous military expedition onto the British people and destroying trust in the state. The lamentations that accompanied the publication of the ‘Chilcot’ Inquiry report are highly personalised. They frame the historical error as one man’s doing. Simon Kuper of the Financial Times claimed that Blair’s ‘faith in his own star convinced him he was right about Iraq’s supposed weapons of mass destruction. He then charmed Parliament and voters into war. Nobody forgives being seduced and then deceived, which is why most Britons now despise Blair’. For columnist Lucy Webster of the Guardian, it was ‘his decision’, just as for the Economist it was ‘the decision of Tony Blair’. Effigies of Blair were common at anti-war rallies. Calls for impeachment focus overwhelmingly on the former PM. One waiter attempted a citizen’s arrest.

Populist politics

This memory of Iraq helps generate the rhetoric of populist politics today, which casts ‘the will of the people’ against corrupt elites. Tony Benn anticipated this rhetoric when he interviewed Saddam Hussein in February 2003, telling the Iraqi ruler that ‘the real British people’ favoured a peaceful outcome. Jeremy Corbyn, now Leader of the Opposition, apologised for the Iraq war and blamed a ‘small number of leading figures in the government’ for misleading Parliament. On his campaign against the ‘swamp’, Donald Trump raised Iraq repeatedly. Blair governed in presidential style, preferring deliberation in his Downing Street ‘den’ to Cabinet. On the day Chilcot was released, an unrepentant Blair accepted ‘responsibility’.

Is it so easy, though, for one man to move a sprawling, disputatious democracy into a war – a preventive war against a hypothetical threat, at that – if it was reluctant? Even in authoritarian states, governments must carry opinion. Wars require domestic coalitions of interests and factions. Furthermore, participants now have an obvious interest in pinning responsibility on one figure. It deflects attention from their own record.

The undertaking was, rather, a collective decision, born of shared ideas and a momentum that flowed from multiple centres of opinion. Blair was not all-powerful. By March 2003, his government was six years old and jaded, no longer that of ‘Cool Britannia’. He faced major obstacles to domestic reform from within his Cabinet and beyond. He was frustrated in his efforts to ‘modernise’ the civil service. His Chancellor, Gordon Brown, outflanked him on the euro. It took a coalition of independent, influential minds to make war possible. The war was intended to have benign effects on the Middle East. Intelligence chiefs believed so. The head of Britain’s SIS, Richard Dearlove, advised that, though difficult, the invasion would be a stride towards wider disarmament and it would alter mentalities. Like Blair, he spoke of a ‘prize’: because it could give new security to oil supplies, engage a powerful, secular state against Sunni extremist terror, open political horizons in the Gulf Cooperation Council states and remove a threat to Jordan and Israel.

The ‘dodgy dossier’ had the willing hand of intelligence officials, who were convinced the WMD programme was real. Though Blair’s introduction to it had unwarranted certitude, the error of leaning too heavily on ambiguous evidence was not his alone. Even sceptics in the Foreign Office and Ministry of Defence were nourished on an optimistic account of influence. They believed that British participation would at least restrain the US.

Another important source of belligerence was Rupert Murdoch, who was not subject to Blair’s whip. All of his 175 newspapers worldwide supported the invasion. Often depicted as a mere cut-throat businessman, Murdoch came to the Iraq question through deep ideological commitments. Murdoch held and promoted the neoconservative vision of US greatness that marries democratic idealism with military assertiveness, using its hegemony to transform nations. Long before Blair took office, Murdoch sponsored the Weekly Standard, America’s foremost neoconservative publication – which he maintained at a loss – whose signature project was the liberation of Iraq. His media embraced the ‘Bush Doctrine’. Britain’s ‘Sun King’, of his own volition, agitated for Blair to strike. In the week before the Commons war vote, he phoned Blair to urge against delay.

Blair also had no control over the opinions of Iraqis living in exile, many of whom supported regime change. In Edinburgh, three presented Blair with a letter urging him to depose Saddam, claiming most Iraqi citizens ‘would back a war’. Iraqi exiles – especially those around Ahmed Chalabi – helped convince London and Washington that a pro-Western democratic revolution in Iraq was the likely result and fed dubious intelligence sources to firm up the case. Iraqi politics is often left out of the narrative, as we focus on western missteps and deceits. But the invasion and its implosion can not be understood without it.

Broader opinion, too, was more accepting of war than we think. Britons remember opposing it, but, according to 21 polls carried out by YouGov between March and December 2003, most supported it at the time, albeit in muted form. Within the commentariat the cause of regime change straddled Left and Right, ranging across the ideological spectrum from Paul Johnson, Melanie Phillips and Anne Leslie to David Aaronovitch, John Lloyd and Nick Cohen. Defeat would prove an orphan. The Economist that later judged it ‘obvious’ that occupying Iraq made international terrorism worse, which reported the ‘damning’ conclusion that an adapted strategy of inspections and containment could have succeeded, is the same journal that, in February 2003, called for Saddam to be disarmed by force if necessary.

Those who would make this issue an indictment of Blair will claim that his cabal misled others of good faith into supporting hostilities. This has been the retort of columnists such as Matthew Parris (‘we believed what we were told’). Gordon Brown, having told the Iraq Inquiry that he still supported the decision, discovered only last year that he would have opposed it had he been aware of a US intelligence report that admitted there was little firm evidence of Iraqi WMDs.

Washing of hands

This hand-washing will not do. To advocate war in 2003 was not merely to accept intelligence estimates about the state of one regime’s arsenal; though there were credible, dissenting reports available from the UN and the International Atomic Energy Agency. To support the invasion was to judge that war would work. It was to accept a trinity of ideas that were the war’s foundation: that we cannot live with rogue states who are undeterrable; that the path to security is to break and remake states; and that the UK must align with the US to constrain its behaviour.

These ideas were brought before Parliament for a vote on 18 March 2003. This was not a war launched by the fiat of Royal Prerogative in the dead of night, but by debating military action for the first time since the Korean War of 1950. The government whips were not confident of enough support. On this vote depended not only the recourse to military action, but Blair’s premiership itself. He had his resignation papers ready. MPs were not compelled to accept his estimate. Weapons inspectors were reporting increased Iraqi co-operation and a dearth of hard evidence for illegal WMD programmes.

Parliament deliberated under the pressure of a military build-up in the Gulf as summer approached. Yet the majority of MPs still chose to accept Blair’s argument, that the risks lay overwhelmingly on one side of the equation. They accepted his case that bringing down the government of a country subject to internal distress amounted to ‘caution’, compared with containing and deterring the regime’s behaviour, all while still shouldering the burden of occupying Afghanistan. Parliament went along with the self-contradictory claims that Iraq, immiserated under the weight of sanctions, could quickly produce a nuclear weapon, with enough infrastructure and scientific-industrial base intact; that the unstable and reckless regime that apparently already possessed stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons had possessed such weapons yet not used them for 15 years, not even when at war with the US or when firing missiles at Israel; and that a reckless, undeterrable regime would go to the trouble of transferring weapons to third parties in order to threaten the West while avoiding retaliation.

They elected, too, to follow what Lawrence Freedman calls ‘the lure of the decisive’, a vision of war that had built up over a succession of seemingly victorious, quick and cheap campaigns: in Kuwait, Sierra Leone, Bosnia, Kosovo and the early phases of Afghanistan. This was the overconfidence in military power with a utility beyond defence and deterrence, as a problem-solving instrument that would create an Iraq fractured by divide-and-rule politics, a harmonious democratic client state that would precipitate a consensual process of reform. The war was conducted ‘in our name’ by our representatives in a parliamentary democracy.

Regime change

Many of the ideas that drove that collective decision are still with us, long after the cast retired. London has demanded repeatedly that this or that regime ‘must go’, whether in Damascus or Tripoli. In doing so, it has underestimated the resistance of adversaries and presumed too much of its own knowledge. It has supported revolts, often without looking closely at who it is supporting on the ground. The Foreign Affairs Select Committee found in its inquiry over the Libyan intervention of 2011 that decision-makers gravely underestimated the extent to which rebel groups were pervaded by armed Islamists. Anglo-American support for Syrian rebels ran into similar problems. Guns and money ended up flowing into the hands of Islamist groups, who were themselves partly the creations of the war in Iraq. And the Afghanistan war persisted, with repeated false assurances by generals and ministers of a ‘decisive’ campaigning season.

Today, the discourse around British security is not one of prudent war avoidance or defined means and ends. Rather, it is ‘learning the lesson’ that ‘we’ must deliver security after overthrowing a regime, using Western power to prevent conflict, fix broken states and almost routinely project military power with little regard for the political will or agency of host populations. The anxiety to remain at the international top table endures, not only to be a solid ally but to stand in uniquely close alignment with the US, in order to constrain it, despite all evidence to the contrary. Blair’s audiences were predisposed to believe and support such conceits then. The same ideas live on.

If Blair is despised over Iraq it is partly because despising another party is easier than self-examination. Many agreed with him because they were predisposed to. They eagerly consumed the intelligence and accepted the assurance that war would work. Thus, the Iraq reckoning is about more than one campaign. It is about our assumptions about security and power, about democracy and responsibility. To understand the Iraq misadventure, we should go beyond fixation with Blair, who at least is willing to face the inquest and the music. Are we?

Patrick Porter is Professor of International Security and Strategy at the University of Birmingham. He is the author of Blunder: Britain’s War in Iraq (Oxford, 2018).

Adaugă un comentariu

© 2024 Created by altmarius.

Oferit de

![]()

Embleme | Raportare eroare | Termeni de utilizare a serviciilor

Pentru a putea adăuga comentarii trebuie să fii membru al altmarius !

Alătură-te reţelei altmarius