http://cdn8.openculture.com/2017/06/14231422/aristotle-egypt-150x139.png 150w, http://cdn8.openculture.com/2017/06/14231422/aristotle-egypt-300x27... 300w, http://cdn8.openculture.com/2017/06/14231422/aristotle-egypt-768x70... 768w, http://cdn8.openculture.com/2017/06/14231422/aristotle-egypt-1024x9... 1024w" sizes="(max-width: 1364px) 100vw, 1364px" />

http://cdn8.openculture.com/2017/06/14231422/aristotle-egypt-150x139.png 150w, http://cdn8.openculture.com/2017/06/14231422/aristotle-egypt-300x27... 300w, http://cdn8.openculture.com/2017/06/14231422/aristotle-egypt-768x70... 768w, http://cdn8.openculture.com/2017/06/14231422/aristotle-egypt-1024x9... 1024w" sizes="(max-width: 1364px) 100vw, 1364px" />

In the ancient world, the language of philosophy—and therefore of science and medicine—was primarily Greek. “Even after the Roman conquest of the Mediterranean and the demise of paganism, philosophy was strongly associated with Hellenic culture,” writes philosophy professor and History of Philosophy without any G.... “The leading thinkers of the Roman world, such as Cicero and Seneca, were steeped in Greek literature.” And in the eastern empire, “the Greek-speaking Byzantines could continue to read Plato and Aristotle in the original.”

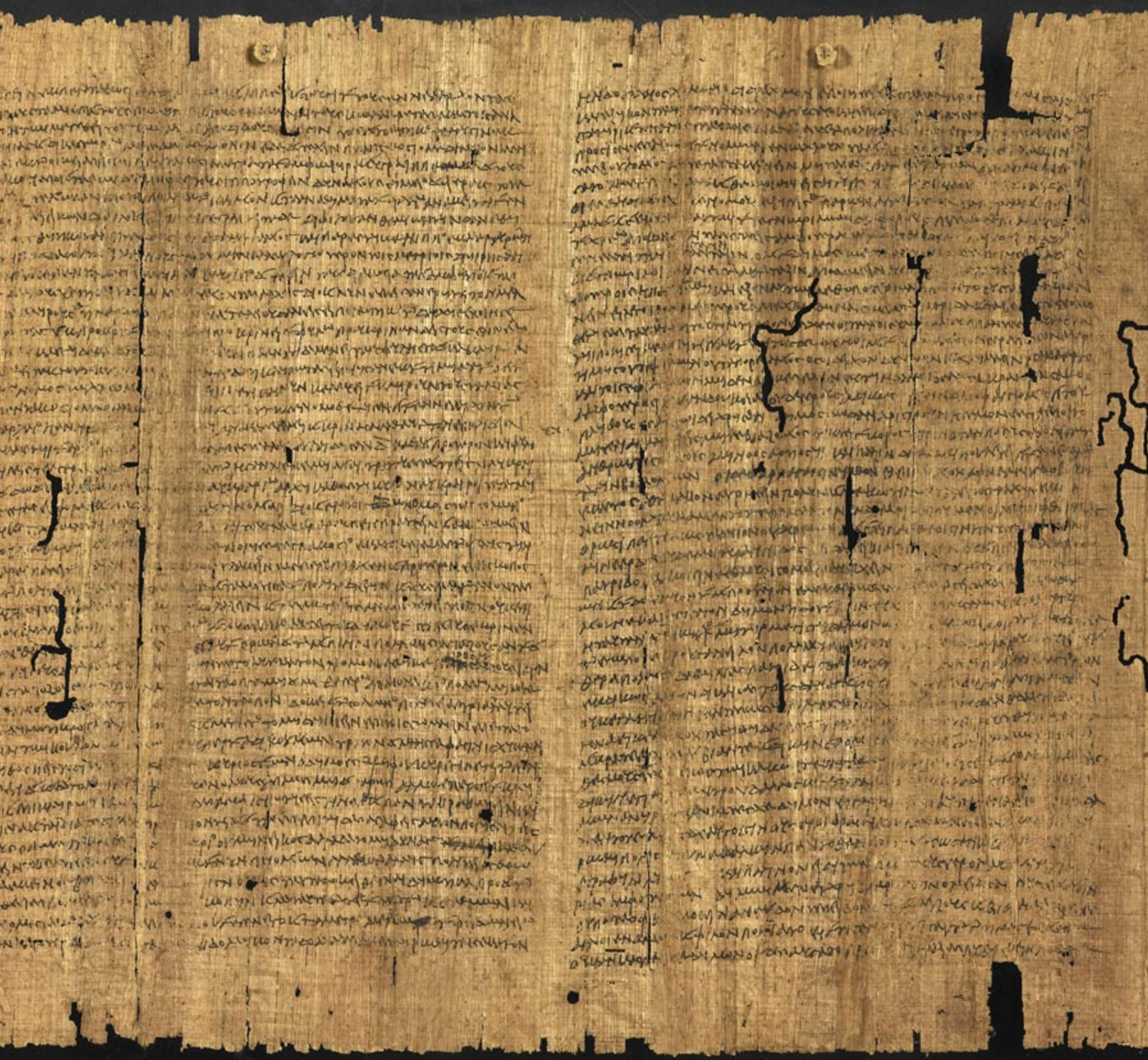

Greek thinkers also had significant influence in Egypt. During the building of the Library of Alexandria, “scholars copied and stored books that were borrowed, bought, and even stolen from other places in the Mediterranean,” writes Aileen Das, Professor of Mediterranean Studies at the University of Michigan. “The librarians gathered texts circulating under the names of Plato (d. 348/347 BCE), Aristotle and Hippocrates (c. 460–c. 370 BCE), and published them as collections.” The scroll above, part of an Aristotelian transcription of the Athenian constitution, was believed lost for hundreds of years until it was discovered in the 19th century in Egypt, in the original Greek. The text, writes the British Library, "has had a major impact in our knowledge of the development of Athenian democracy and the workings of the Athenian city-state in antiquity."

Alexandria “rivalled Athens and Rome as the place to study philosophy and medicine in the Mediterranean,” and young men of means like the 6th century priest Sergius of Reshaina, doctor-in-chief in Northern Syria, traveled there to learn the tradition. Sergius “translated around 30 works of Galen [the Greek physician]” and other known and unknown philosophers and ancient scientists into Syriac. Later, as Syriac and Arabic came to dominate former Greek-speaking regions, the Greek texts became intense objects of focus for Islamic thinkers, and the caliphs spared no expense to have them translated and disseminated, often contracting with Christian and Jewish scholars to accomplish the task.

The transmission of Greek philosophy and medicine was an international phenomenon, which involved bilingual speakers from pagan, Christian, Muslim, and Jewish backgrounds. This movement spanned not only religious and linguistic but also geographical boundaries, for it occurred in cities as far apart as Baghdad in the East and Toledo in the West.

In Baghdad, especially, by the 10th century, “readers of Arabic,” writes Adamson, “had about the same degree of access to Aristotle that readers of English do today” thanks to a “well-funded translation movement that unfolded during the Abbasid caliphate, beginning in the second half of the eighth century.” The work done during the Abbasid period—from about 750 to 950—“generated a highly sophisticated scientific language and a massive amount of source material,” we learn in Harvard University Press’s The Classical Tradition. Such material “would feed scientific research for the following centuries, not only in the Islamic world but beyond it, in Greek and Latin Christendom and, within it, among the Jewish populations as well.”

Indeed this “Byzantine humanism,” as it’s called, “helped the classical tradition survive, at least to the large extent that it has.” As ancient texts and traditions disappeared in Europe during the so-called “Dark Ages,” Arabic and Syriac-speaking scholars and translators incorporated them into an Islamic philosophical tradition called falsafa. The motivations for fostering the study of Greek thought were complex. One the one hand, writes Adamson, the move was political; “the caliphs wanted to establish their own cultural hegemony,” in competition with Persians and Greek-speaking Byzantine Christians, “benighted as they were by the irrationalities of Christian theology.” On the other hand, “Muslim intellectuals also saw resources in the Greek texts for defending, and better understanding their own religion.”

One well-known figure from the period, al-Kindi, is thought to be the first philosopher to write in Arabic. He oversaw the translations of hundreds of texts by Christian scholars who read both Greek and Arabic, and he may also have added his own ideas to the works of Plotinus, for example, and other Greek thinkers. Like Thomas Aquinas a few hundred years later, al-Kindi attempted to “establish the identity of the first principle in Aristotle and Plotinus” as the theistic God. In this way, Islamic translations of Greek texts prepared the way for interpretations that “treat that principle as a Creator,” a central idea in Medieval scholastic philosophy and Catholic thought generally.

The translations by al-Kindi and his associates are grouped into what scholars call the "circle of al-Kindi," which preserved and elaborated on Aristotle and the Neoplatonists. Thanks to al-Kindi's "first set of translations," notes the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "learned Muslims became acquainted with Plato's Demiurge and immortal soul; with Aristotle's search for science and knowledge of the causes of all the phenomena on earth and in the heavens," and many more ancient Greek metaphysical doctrines. Later translators working under physician and scientist Hunayn ibn Ishaq and his son "made available in Syriac and/or Arabic other works by Plato, Aristotle, Theophrastus, some philosophical writings by Galen," and other Greek thinkers and scientists.

This tradition of translation, philosophical debate, and scientific discovery in Islamic societies continued into the 10th and 11th centuries, when Averroes, the "Islamic scholar who gave us modern philosophy," wrote his commentary on the works of Aristotle. "For several centuries," writes the University of Colorado's Robert Pasnau, "a series of brilliant philosophers and scientists made Baghdad the intellectual center of the medieval world," preserving ancient Greek knowledge and wisdom that may otherwise have disappeared. When it seems in our study of history that the light of the ancient philosophy was extinguished in Western Europe, we need only look to North Africa and the Near East to see that tradition, with its a humanistic exchange of ideas, flourishing for centuries in a world closely connected by trade and empire.

Related Content:

Learn Islamic & Indian Philosophy with 107 Episodes of the Hist...

Ancient Maps that Changed the World: See World Maps from Ancient Gr...

Introduction to Ancient Greek History: A Free Online Course from Yale

Free Courses in Ancient History, Literature & Philosophy

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Pentru a putea adăuga comentarii trebuie să fii membru al altmarius !

Alătură-te reţelei altmarius