cultură şi spiritualitate

“Dada doubts everything,” wrote the poet-performer and Dada founding member Tristan Tzara in 1920. Born in a Zürich nightclub in 1916 as an all-out mutiny against World War I and the social and political climate that fueled it, Dada remains one of the most anarchistic cultural movements of all time.

But while Dada had no problem questioning authority, meaning, reality, and everything else related to what they saw as a bourgeois Western world, its practitioners rarely, if ever, cast doubt on conventional gender roles and behaviors. Even if the social conservatism that yielded such inequality was disdained, women were the second sex.

For a long time, women who identified with Dada as visual artists, poets, or performers (or often all three) drew more attention as caretakers, muses, or lovers than collaborators or independent artists. One of the rare mentions Dada legend Hannah Höch received in her male peers’ accounts of the era was reportedly a nod to her talent at providing sandwiches, beer, and coffee during tough times.

But more recently, as art historians and curators have shined a brighter light on this electrifying period of creative rebellion, it has become clear that women were active artmaking participants in Dada’s spaces, from cafes and salons to specialty magazines and exhibitions. Here are eight female artists who made vital contributions to the movement.

Hannah Höch

B. 1889, GOTHA, GERMANY

D. 1978, BERLIN

-

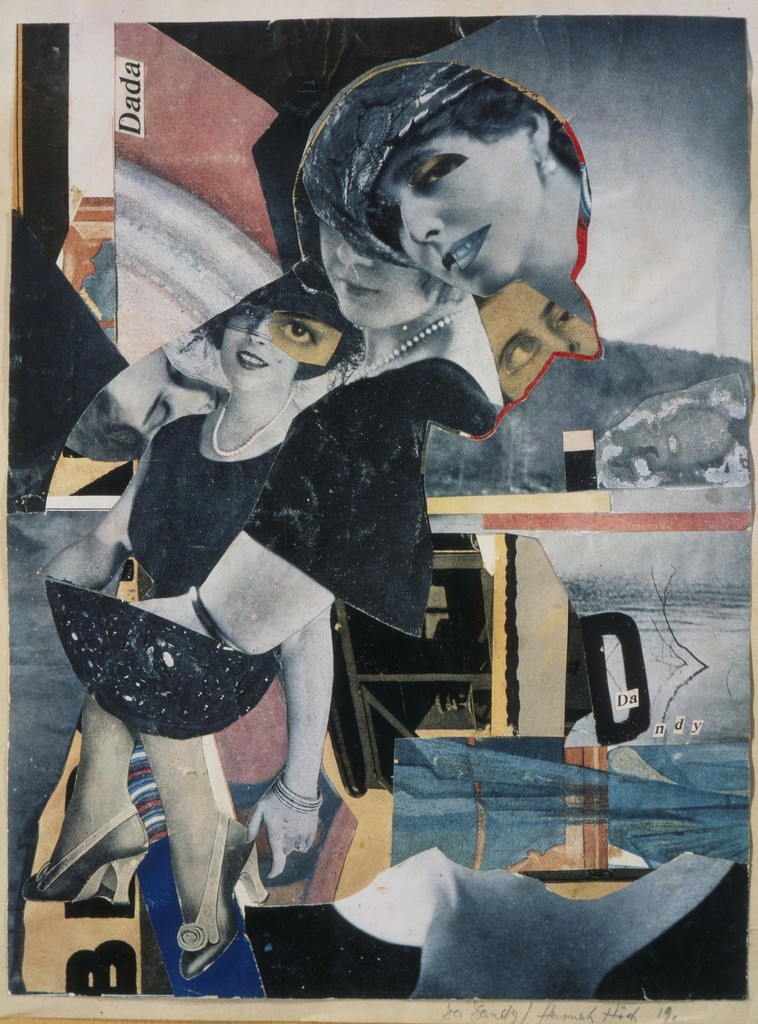

Private Collection, Berlin

-

Für ein Fest gemacht (Made for a Party) , 1936

An early pioneer of photomontage and mass-media appropriation, Höch was a cornerstone of the most political branch of the Dada movement, the one that developed in Berlin. Formed after World War I, Berlin’s Dada group had a direct target—the Weimar Republic and its leaders—and Höch, like her Berlin colleagues John Heartfield, George Grosz, and Raoul Hausmann (her lover, for a period), mined newspaper and magazine imagery for political satire.

But the fiercely feminist Höch also used art to draw attention to women’s issues, like birth control and suffrage. Hoch had studied graphic arts and design before going to work in publishing, where she made sewing patterns for women’s magazines. The ads she encountered in print fueled her rebellion against the commercial construction of femininity. (It’s easy to detect Höch’s use of appropriation in the work of Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, and other artists of the Pictures Generation.)

Hoch exhibited at the subversive International Dada Art Fair in Berlin in 1920. That year, she also penned a short story, “The Painter,” in which she takes aim at male chauvinism: The tale portrays a husband who descends into a personal crisis when his wife requests that he does the dishes four times in four years.

Suzanne Duchamp

B. 1889, BLAINVILLE-CREVON, FRANCE

D. 1963, PARIS

Duchamp had to not only carve out her own identity as a female Dada artist working in Paris during the war, but also shake the “sister of Marcel Duchamp” label that still pursues her to this day. The small trove of delicate paintings and drawings she left behind shows her serious and early devotion to Dada experimentation.

After studying art at the École des Beaux-Arts, Duchamp worked as a nurse during the war while her brother ditched Europe for New York. In 1916, the artist Jean Crotti, who had collaborated with Marcel in America (and who Suzanne would marry) returned to Paris with tales of the wild, avant-garde art coming out of the New York branch of Dada. Energized by the news, Suzanne began making drawings that juxtaposed text with machine imagery, a popular Dada trope.

While her work doesn’t possess the clear feminist impulses of some of her Dada sisters, she did address gender inequality in a 1916 collage, Un et une menacés (A Menaced Male and Female), whose opposing mechanical parts read as a couple destined never to connect. She didn’t gain the same notoriety as other members of the Dada cohort in Paris, but she was taken seriously enough to exhibit with them at the Salon des Indípendants in 1920, the first Dada exhibition in the French city, which was organized after the arrival there of André Breton, Tristan Zara, and Francis Picabia.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp

B. 1889, DAVOS, SWITZERLAND

D. 1943, ZÜRICH

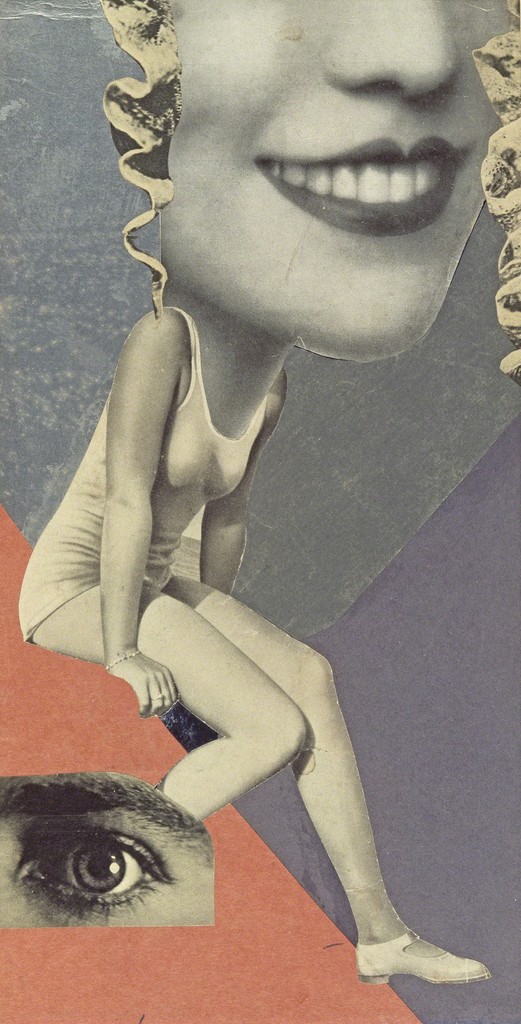

Taeuber-Arp studied textile design and taught in a design school in Zürich, and she’s best remembered for the abstract oil paintings, watercolors, embroideries, and sculpture she made during the war. But as an exceptionally multi-talented dancer and innovator of performance art, she was integral to the development of Dada in the Swiss city.

In Zurich, Dada was particularly collaborative and performance-oriented, centering around the infamous Cabaret Voltaire and the Galerie Dada, where the resistance, including artists and writers drawn to Switzerland for its neutrality, came to witness and participate in highly creative live action. The native Swiss Taeuber-Arp was a core performer, having studied dance with one of Zürich’s most prestigious choreographers, and her “abstract dances,” as they were called, were like nothing the public had seen before. She also collaborated with her artist-poet husband Jean Arp to make bizarre costumes and elaborate marionettes for the shows.

Beatrice Wood

B. 1893, SAN FRANCISCO

D. 1998, OJAI, CA

Beatrice Wood, Is My Hat on Straight?, 1969. Courtesy of Francis M. Naumann Fine Art.

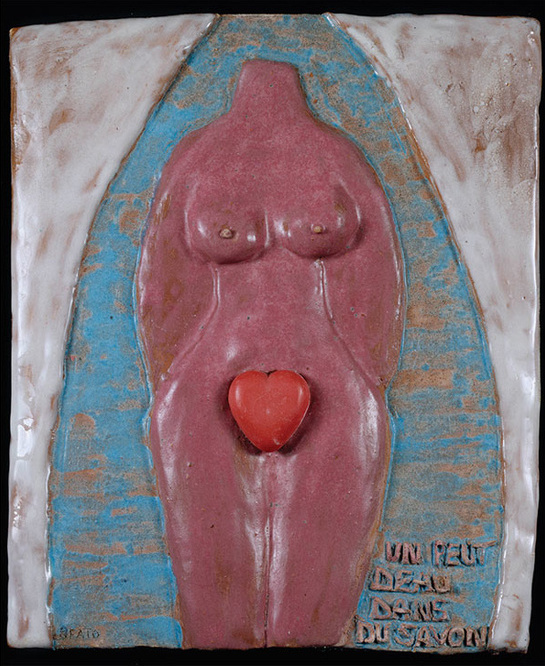

Beatrice Wood,Un peut d’eau dans du savon, ca. 1980. Courtesy of Francis M. Naumann Fine Art.

Soon after the San Francisco-born Wood met Marcel Duchamp through composer Edgard Varèse, she flippantly suggested to the artist that anyone could “do modern art.” He told her to go home and do it, and that’s exactly what she did.

Wood’s socialite parents had sent her to Paris years earlier to study painting and drawing, in a fruitless attempt to satisfy her rebellious streak, and she had developed a keen set of artistic skills. So she returned to Duchamp with a drawing—a vaguely representational image suggesting the suffocation of marriage. Duchamp was impressed, and the two became friends. He encouraged her to present two paintings at the first exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, in 1917. There, she shocked visitors by showing Un peut (peu) d’eau dans du savon, a painting of a female nude with a heart-shaped bar of soap placed strategically between the legs.

Around the same time, Duchamp and Wood, along with writer Henri-Pierre Roché, founded The Blind Man, a short-lived Dada magazine that published art and text by anyone who was anyone in New York’s cutting-edge art scene. Wood sculpted as well, and later made her mark as an important California studio potter. She is still sometimes remembered for her love triangle with Duchamp and Roché, which inspired the 1962 film Jules et Jim.

Clara Tice

B. 1888, ELMIRA, NY

D. 1973, QUEENS, NY

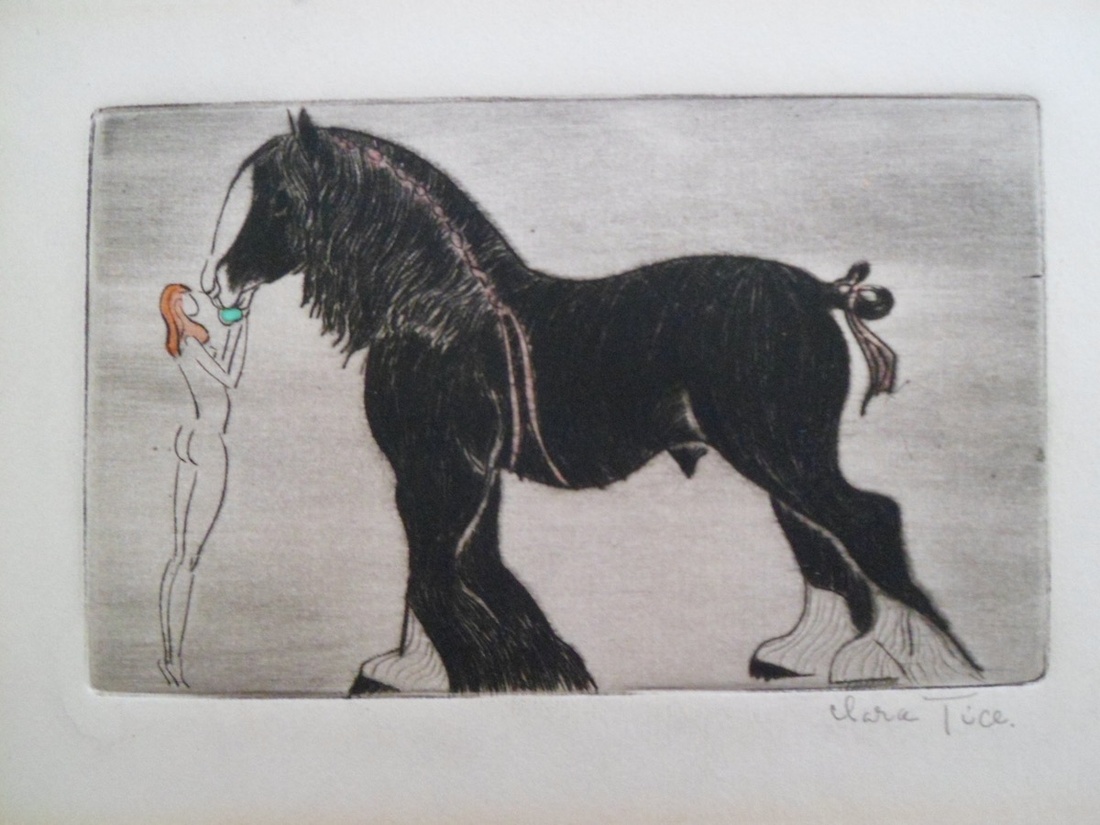

Clara Tice, Nude Woman Feeding Horse. Courtesy of the artist.

A young Tice catapulted to Greenwich Village stardom when the morality police—the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice— raided a café in 1915 in search of her erotic drawings. The well-publicized event secured her status as a downtown curiosity and drew the attention of some of the city’s edgier editors. But there’s no doubt that Tice would have made a name for herself even without that publicity boost.

Her drawings and etchings of women—stylish soft porn rendered with an economy of detail—became quickly sought-after (and enraged some critics), and she set off on a successful career as an artist and illustrator, drawing for magazines like Vanity Fair, illustrating books, and showing her work on the walls of downtown’s most fashionable garrets. She also had a fashion-forward style all her own and became known as the “Queen of Greenwich Village.” Some say she invented the bob hairstyle.

Thumbing her nose at bourgeois social mores, she fell in with the Dada crowd at the home of Walter and Louise Arensberg—major Dada collectors, patrons, and intellectuals who held salons at their 67th Street home. While her work had its sassy commercial appeal, it also appeared in the Dada journal The Blind Man and in the first exhibition of the avant-garde Society of Independent Artists.

Ella Bergmann-Michel

B. 1896, PADERBORN, GERMANY

D. 1971, EPPSTEIN, GERMANY

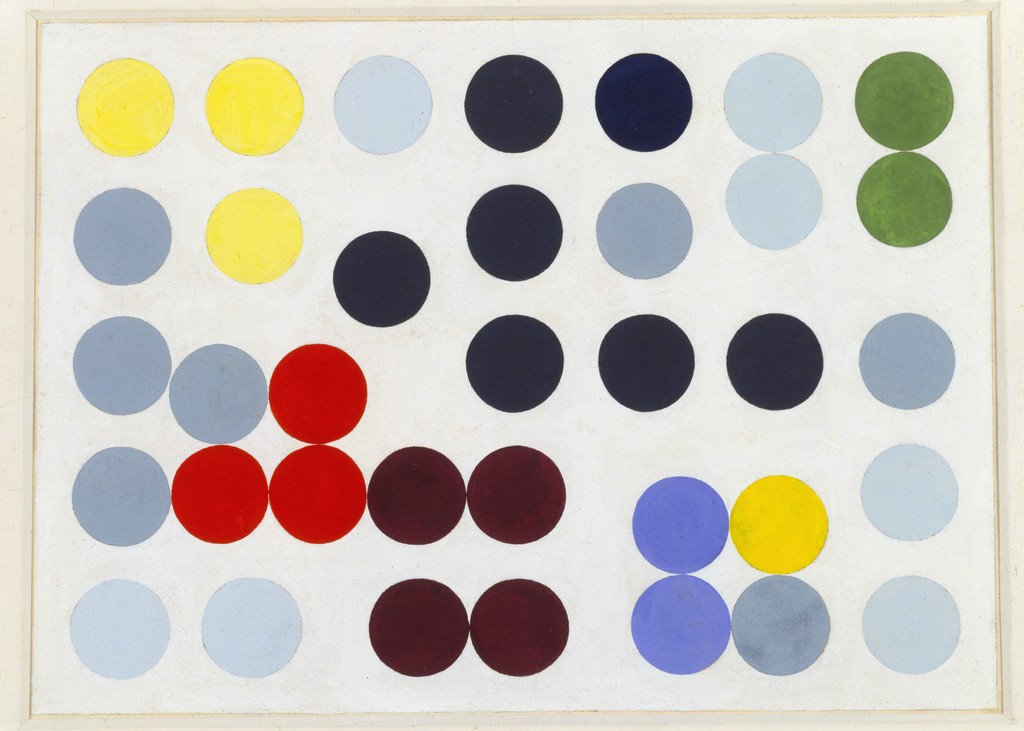

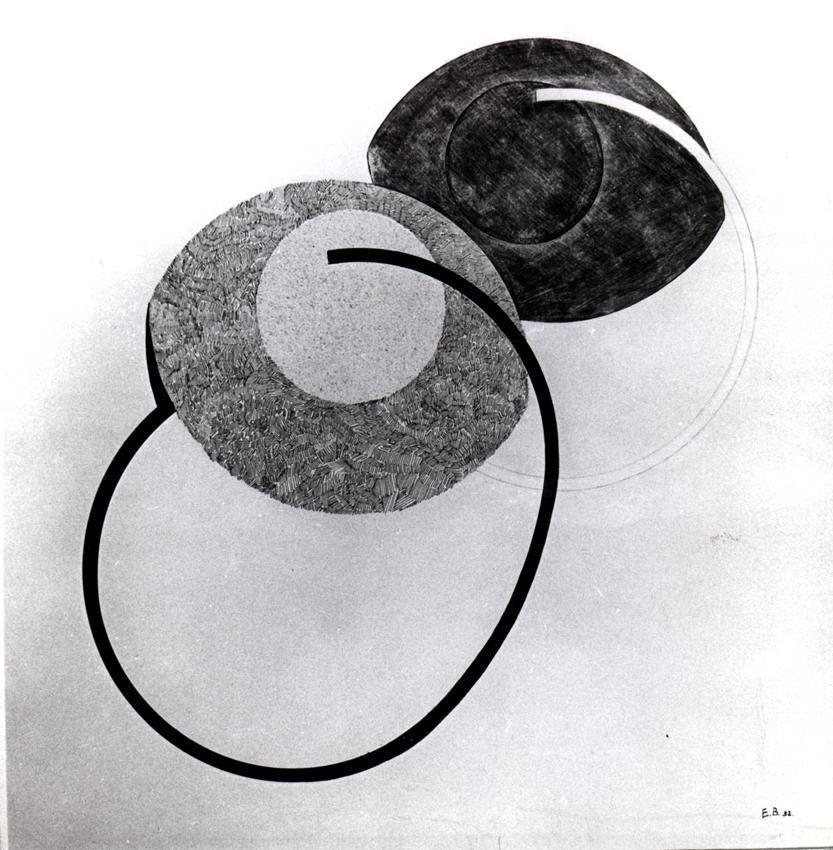

After studying art in Weimar and developing a relationship with the artist Robert Michel, who would become her husband and part-time collaborator, Bergmann-Michel was associated with the Bauhaus for a short time before moving on to more Dada-inflected endeavors. The couple hosted Dada meetings and worked on photo collages at their home in Vockenhausen, near Frankfurt.

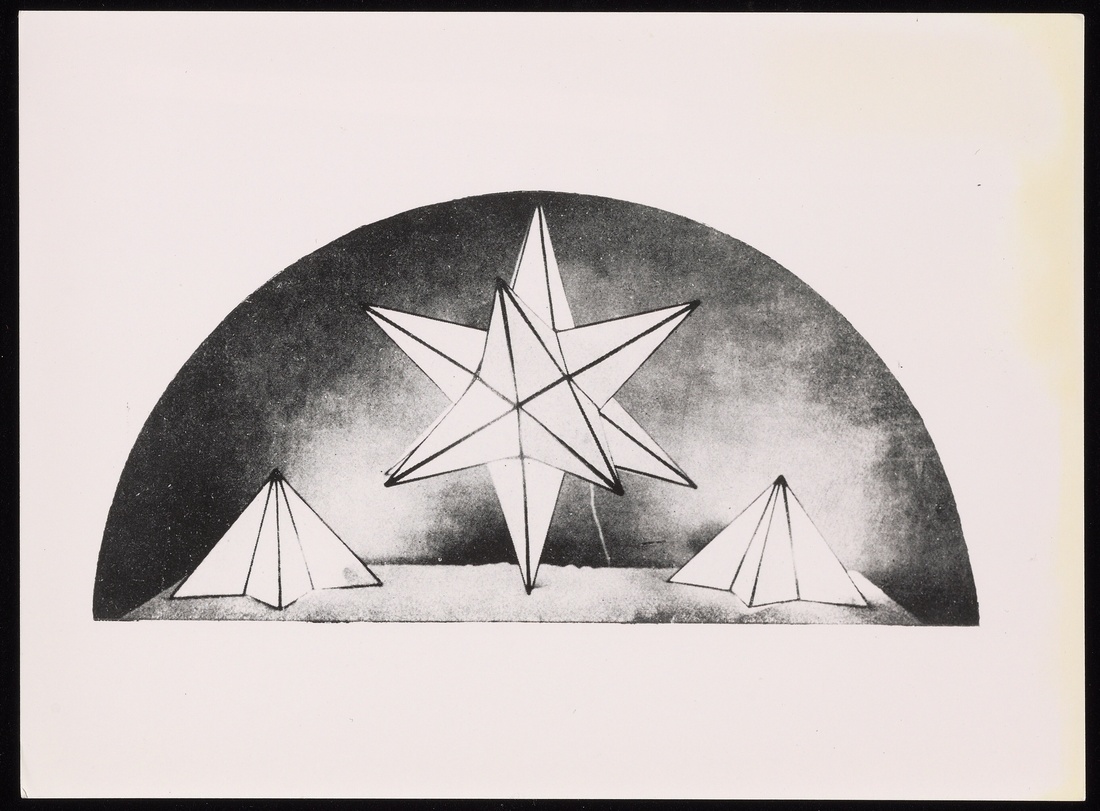

In Bergmann-Michel’s abstract, constructivist drawings, geometric components become vaguely dystopian, precarious mechanisms that suggest a metaphor for civilization gone awry. She might be all but forgotten if Man Ray, Duchamp, and Katherine S. Dreier hadn’t included her and Michel’s work in the Société Anonyme, the organization they founded in 1920 to show avant-garde European art in America.

Bergmann-Michel went on to make documentaries in the 1930s. Her artwork was especially scarce until the discovery, in the 1980s, of a trove of drawings likely hidden from the Nazis in a mill where she and Michel had lived in 1920.

Mina Loy

B. 1882, LONDON

D. 1966, ASPEN, CO

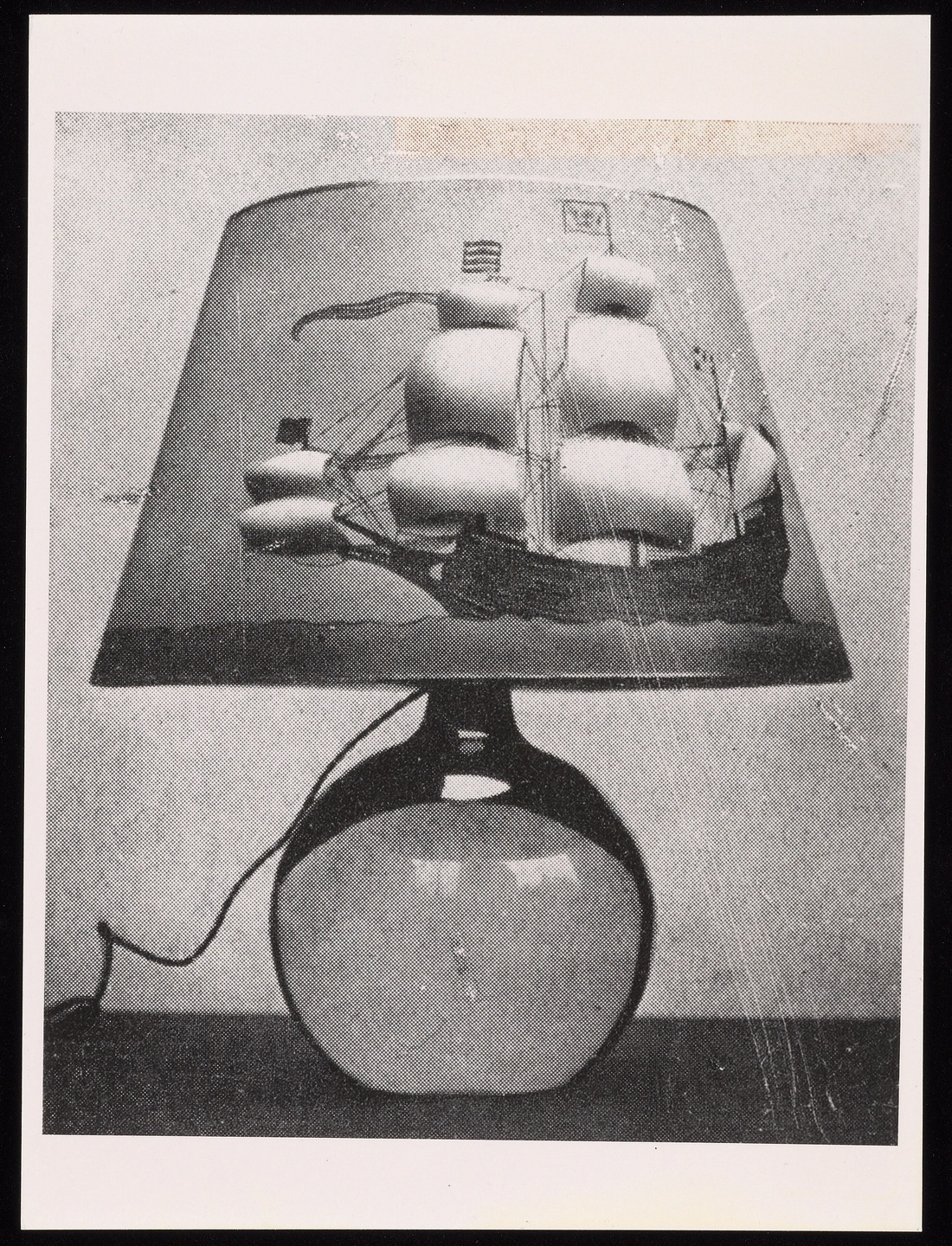

Mina Loy, Lamps photographs by Charmet, Jean-Loup Photos Presse Paris, ca.1920. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University.

Mina Loy, Lamps photographs by Charmet, Jean-Loup Photos Presse Paris, ca.1920. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University.

The British-born Loy was a regular at Gertrude Stein’s salons in Paris, and dabbled in Futurism while living in Florence before moving to New York in 1916. When she arrived in the States, she was already known in literary circles, not only for her 1914 “Feminist Manifesto,” in which she called on women everywhere to break with social conventions and live sexually liberated lives, but for her poetry, whose praises were sung by T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound.

Fashionable, frisky, and brainy, she fit right in with the happening bohemian scene that Duchamp belonged to. Her shockingly frank poetry—erotic, personal, and uninhibited when it came to bodily functions—appeared in vanguard literary magazines like The Blind Man, Others, and Rogue, but Loy also painted, drew, acted, and had an unusual affinity for lampshades. She depicted them, dressed as one at a costume ball, and later started a business selling them in Paris, backed by Peggy Guggenheim.

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

B. 1874, SWINEMÜNDE, GERMANY (NOW ŚWINOUJŚCIE, POLAND)

D. 1927, PARIS

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhovento, God, 1917. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Fusing art and life was one of the guiding principles of Dada, and von Freytag-Loringhoven did it with flair. A German-born fixture of New York’s downtown scene in the late 1910s and early ’20s, the fearless and eccentric Baroness made assemblage art and collages, and wrote poetry, as well as modeling and performing. But she might have been most famous for her bizarre getups. On any given day, she might have been wearing a soup-can bra or a hat decorated with dangling spoons or feathers—like a sort of streetwise flapper gone mad. Or she might have been semi-nude, a crime for which she was arrested multiple times.

Although extravagant in style, von Freytag-Loringhoven lived like a pauper, having received her royal title from her marriage (her third) to the penniless Baron von Freytag-Loringhoven, who joined the war in Europe and never returned. But her close circle of New York artists and intellectuals—Duchamp, William Carlos Williams, and Djuna Barnes—ensured a rich cultural life.

She wrote poems about Duchamp, painted an amusing interpretive portrait of him, and some have even conjectured that it was Freytag-Loringhoven herself who came up with the idea of Duchamp’s famous urinal, and sent it to him signed R. Mutt.

—Meredith Mendelsohn

Header images, from left: Portrait of Hannah Hoech, 1973, by Will/ullstein bild via Getty Images; Portrait of Beatrice Wood, circa 1990, by Nancy R. Schiff/Getty Images; Portrait of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhovento via Flickr.

Adaugă un comentariu

© 2024 Created by altmarius.

Oferit de

![]()

Embleme | Raportare eroare | Termeni de utilizare a serviciilor

Pentru a putea adăuga comentarii trebuie să fii membru al altmarius !

Alătură-te reţelei altmarius