cultură şi spiritualitate

David Andress provides a nuanced history of the French Revolution, which shows that its facts are anything but fixed.

What the French Revolution was depends, perhaps more than any other major historical event, on what you choose to believe about it. Was it a great epoch in the history of the modern West, or an ugly and unnecessary carnage? Was it the product of the collapse of the French state from inside, or of irresistible social pressures? Was it a brave attempt to create a constitutional state betrayed by irresponsible radicals, or a radical bid to bring happiness to the world betrayed by compromisers and aristocrats? Was it a doomed descent into anarchic violence, or a desperate, but managed, effort to resist enemies on all sides?

It has been all these things, not just in the longer term of history, but within the debates and memories of its participants. Every subsequent generation has imposed its ideas and concerns onto the fabric of revolutionary events but none has succeeded in doing more than establishing a temporary supremacy of one prevailing view or another.

A complete history of the French Revolution can only be a review of events so disturbing to their contemporaries – and so central to modern politics – that assigning them a fixed significance continues to elude us. If that seems disappointing, it should not be, because history is not about settled questions (for those, a mere chronicle will suffice). Rather, we should see in the endlessly disturbed waters of debate on this subject a better reflection of the unsettled, unfinished nature of society today and a stronger reason to continue debating it into the future.

***

There is a straightforward explanation for the events that became the Revolution: the French state was lurching towards bankruptcy. Burdened with massive debts accumulated through military expenditure in the Seven Years’ War and the War of American Independence, unable to raise enough in taxation to pay down the debts, coming dangerously close to borrowing more simply to keep the government’s candles lit, Louis XVI’s ministers were, by the mid-1780s, in dire straits (see Peter Burley for a detailed exploration of French finances).

They could simply have repudiated the debts, either by blatantly cancelling them or through forms of restructuring that many states, including France itself, had used on occasion in previous centuries. The revolutionary situation arose precisely because ministers felt compelled not to do this. The influence of a culture of ‘Enlightenment’, a belief in the value of public debate and of ‘public opinion’ as a worthy judge of state actions, hovered in their minds. So, too, did the knowledge that the idea of state bankruptcy had already been branded as a hallmark of evil despotism in the writings of eminent commentators.

Interactive: Key Figures in the French Revolution

This insight allows us to see another dimension of the traditional debate between the social and the political origins of the Revolution. Historians in the last 40 years have tended to move away from thinking about social class as a cause of conflict: the evidence for a strong capitalist bourgeoisie before 1789 was always thin and faded away under detailed inspection (see Maurice Cranston for a bicentennial reflection on 1789). This has opened the field to revived interest in the worldview of elite individuals – ministers themselves and the 144 noblemen invited in 1787 to form an ‘Assembly of Notables’ to approve royal reforms. Many of these rejected the proposals, using an intriguing cocktail of reasons that both defended their privileged place in the state and talked of the wider interests of the ‘nation’ against the crown.

***

In so doing and in continued defiance of royal plans by France’s network of high courts, the parlements, over the next year the elite attracted a great deal of support from the public. That public was an unmeasurable mix of the two or three per cent of the country who were nobles and clergy, another few per cent who made up a wider educated and propertied class of commoners and a more visible public of urban protesters who supported their local institutions with vociferous protest. This was particularly notable in the summer of 1788, when royal despotism seemed to take a leap forward, abolishing the parlements and seeking to implement changes without them.

By the end of that year, the public had fractured dramatically. Its voice and real looming bankruptcy had forced the crown to give in and restore the parlements. A national consultative Estates General was to be held, the first since 1614, to address grievances and pave the way for reform. The judges in the senior Paris parlement had greeted news of this event, which the nation had cried out for, with a pronouncement that it should meet in three equal chambers, with two reserved for the nobility and clergy. Thus the wider public, the so-called ‘Third Estate’, would lose any chance of a significant voice.

In the tidal wave of protests, petitions and pamphlets that followed it became clear that the coalition against royal despotism concealed a deep divide. The privileges of nobility, their legal rights to be different from, and superior to, others, paying fewer taxes and milking the state for support were in their own eyes perfectly compatible with ideas of anti-despotic liberty. In the view of others, however, they were themselves a form of tyranny, which talk of the nation and an Estates General had already seemed to undermine. There may not have been a strong capitalist bourgeoisie, but there was a strong enlightened public, whose ideas of individual freedom and equality – against privilege, if not in material terms – were just as corrosive.

Clothing worn by the three orders of the Estates General: the clergy, the nobility and the common people, 1789France ended 1788 with the edifice of royal power tottering. The crown had decreed at the last moment that the Third Estate could have double the Estates General representatives of the other two, but ducked the issue of whether votes would be ‘by head’, leaving the concession moot. The effort to reject an unacceptably old-fashioned solution of bankruptcy had brought on the very accusations of tyranny it had sought to avoid. The necessity to compromise with opposition had led to further rifts. The abbé Sieyès, a commoner who had made his way in the professional ranks of the church, published at the start of the new year 200 pages of vivid prose entitled What is the Third Estate? His answer was that it was currently everything and nothing and that, in comparison, the privileged orders were a ‘malignant tumour’ in the body politic.

Clothing worn by the three orders of the Estates General: the clergy, the nobility and the common people, 1789France ended 1788 with the edifice of royal power tottering. The crown had decreed at the last moment that the Third Estate could have double the Estates General representatives of the other two, but ducked the issue of whether votes would be ‘by head’, leaving the concession moot. The effort to reject an unacceptably old-fashioned solution of bankruptcy had brought on the very accusations of tyranny it had sought to avoid. The necessity to compromise with opposition had led to further rifts. The abbé Sieyès, a commoner who had made his way in the professional ranks of the church, published at the start of the new year 200 pages of vivid prose entitled What is the Third Estate? His answer was that it was currently everything and nothing and that, in comparison, the privileged orders were a ‘malignant tumour’ in the body politic.

The year of the Estates General was an astonishing rollercoaster of hope and dread. It began with communities gathering to take part in elections, an event for which there was a significant level of local precedent, but none in living memory for such a national event. With those elections went the composition of cahiers de doléances, registers of grievances for redress, which were an essential component of the medieval consultative nature of the Estates. After 175 years of absolute monarchy, which had piled up layer upon layer of divisive privileges, often selling them for cash as part of its fiscal strategies, the pent-up volume of social resentment was immense and explosive. As communities unleashed their complaints about the injustice they endured – including the great burden of owing not just taxes and church tithes but also ‘feudal dues’ to local lords – they also felt the immediate burden of a harsh winter after a poor harvest, with food stocks running low and prices in the towns rising dangerously.

***

By the early spring, communities had begun to take direct action. Some claimed they had a licence to fulfil the demands they had made in their cahiers, others voiced the need for justice or simple material need. Tax offices, monastic granaries, noble game reserves, enclosed commons and document rooms of local chateaux all experienced popular wrath up and down the country in sporadic and spontaneous movements. Had it been only a little more consistent, this activity would have been recognised as a mass movement. Many elite observers at the time wrote it off as delusional and it introduced another dimension of complexity to the political landscape: soon, town populations would be forming militias to defend themselves against a peasantry whose motivations they could not decipher and would not trust.

It was in the shadow of all this that the Estates General met at Versailles in early May and for the first month of its existence remained entirely deadlocked. The majority of noble deputies were convinced their social identity was at stake in the pretentions of the Third Estate and resisted all moves to meet together as the latter demanded. Only after the Third had vowed in June to proceed alone, declaring itself the ‘National Assembly’ and pledging to write a new constitution, did privileged resistance crumble. In early July a sudden spark of royal despotism took its place and Louis XVI was persuaded by his family to sack the popular minister Necker and bring in a hard-line ministry that could, they thought, crush the Assembly.

News of this, as well as rumours of menacing troop movements, sparked the uprising of the Parisian population on July 12th that, within 48 hours, had formed a citizens’ militia, seized state armouries and besieged the Bastille to secure its stocks of gunpowder. News of this rising caused dread in the National Assembly and only unequivocal word that it had been done on their behalf, which arrived after the fall of the Bastille, broke the immense tension with near hysterical relief. The king arrived at their meeting hall on the 15th to pledge to work with them. This and a ceremonial royal visit to Paris on the 17th, where Louis was greeted by the city’s new revolutionary authorities, cemented a sense of epoch-making change. But the first counter-revolutionary aristocrats, including the king’s brother Artois, had already fled the country, becoming the émigrés whose threat would haunt the coming years.

The Siege of the Bastille by Claude Cholat, 1789

The Siege of the Bastille by Claude Cholat, 1789

Like other aspects of revolutionary action across the country, the extent to which different groups and social constituencies acted both independently towards similar ideals, yet at potential cross-purposes, was remarkable. Soon the Parisian leaders were trying to disarm the less ‘reliable’ (that is, poorer) elements of their militia, while across France the ‘Great Fear’ broke out. Rumours of aristocratically sponsored brigandage, crop-burning and general marauding – almost entirely false – flashed around the nation, mobilising communities (and thus sparking further rumours) and also bounced back to Versailles, creating the impression of a universal collapse of order. In a moderately desperate attempt to regain the political initiative, leading reformers in the Assembly proposed that at least some ‘feudal’ and other privileges should be ended.

As a result of this, the ‘Night of 4th August’ saw an emotional crescendo of proposals from nobles, clerics and commoners, sacrificing church income, noble tax exemptions, feudal rights and all the geographical distinctions that had ‘privileged’ different communities and regions against each other. It redefined the nation as a community equal in civic identity and set the stage for the truly momentous Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen a few weeks later. It also proved cripplingly disappointing to the rural population, whose feudal burdens, despite apparent abolition, were largely slated instead to be ‘redeemed’ at the ludicrous price of a lump sum of 20 years’ dues.

***

August 4th was a decisive high point in revolutionary unity. By the end of the month many nobles and clergy were already regretting their lost status, new quarrels were rising over the basic structure of the planned constitution and further rumours of counter-revolutionary plotting, all the way up to the royal family, were swirling. Clashes over proposals for a royal veto exposed further sharp divides, while continuing food shortages in Paris were read by radicals as evidence of a famine plot. News at the start of October that troops arriving at Versailles had been greeted by a ‘counter-revolutionary’ banquet, with the king and queen in attendance, was the spark for a march from Paris, beginning with groups of market women but expanding to include thousands of the National Guard militia.

The ‘October Days’ cost several royal guards their lives and a number of more conservative deputies thought they were lucky to escape with their own. How close Marie Antoinette truly came to a confrontation with knife-wielding intruders remains a mystery, but the king’s agreement to move to the Tuileries Palace in Paris remained, in his own mind, the coerced submission of a prisoner. It was in the shocked international aftermath of this that Edmund Burke began writing his Reflections on the Revolution in France, which placed the National Assembly at the whim of the mob and the whole culture of the country under the hooves of a ‘swinish multitude’.

The National Assembly that followed the royal couple to Paris a few days later had almost two years’ more work ahead of it to complete its new constitution. Nobody knew that at the time and there was still talk of having it done within months, but the structural obstacles to completion soon began to pile ever higher. Roughly a quarter of the membership, mostly nobles and some clergy, were locked in permanent, aggressive, increasingly ‘counter-revolutionary’, opposition. By the end of 1789, after a decision to nationalise church property (thus staving off bankruptcy again), even more of the clergy became intransigent (see Nigel Aston for a discussion of how the clergy first welcomed, then undermined, the Revolution).

The vigour of the ‘counter-revolution’ was one spur to the foundation of a group that soon rose to become a national movement. The Jacobin Club in Paris was initially a gathering of the relatively few radically democratic Assembly deputies, who felt the need to form what we would now call a caucus to defend their positions from reactionary assaults. By the end of 1790 dozens of provincial clubs had joined it, in what was becoming a dense network of correspondence and political identity – but one built, paradoxically, on the idea of politics without party.

The notion, central to their identity, that Jacobins were simply patriots and that it was their enemies who formed a ‘faction’ was echoed in the wider assumptions structuring the revolutionised nation. A tax-paying male electorate of several million ‘active citizens’ was established and structures of local government, administration and the judiciary from the village upwards were made elective. Nobody, however, was permitted to publicly stand for election – this was too divisive. Rather, in interminable processes, electors nominated lengthy lists of individuals they thought worthy for various roles, only finding out at the end whether any had achieved a majority of votes or were indeed willing to serve. It was little wonder, in hindsight, that initially healthy levels of voter participation plunged, after several different elections stretching into 1791, towards a small minority of persistent activists.

***

These ideas of simple, patriotic public spirit existed alongside not just reactionaries and Jacobins, but a huge spectrum of vociferous press and public debate, marked by the refusal to recognise that there was anything like a spectrum of positions involved. The constant cry was of what ‘all the good citizens’ must think, feel, want or fear – and any differing suggestions were denounced, loudly, as unpatriotic, aristocratic, counter-revolutionary. Even voices that were clearly radical in their advocacy of popular engagement could be damned as aristocratic by seeing them as ‘disorganisers’, fomenting chaos through which the émigrés would triumph. Fear of gens malintentionnés – ‘ill-intentioned people’ of unknown identity and dread motive – was everywhere.

As such acrimony flourished, major political decisions fuelled it further. From early 1790, authorities had begun to inventory ‘surplus’ religious buildings for sale, leading to the wholesale abolition of monasticism, as new rules for the state-funded church were finalised that June. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy split that body almost down the middle and with it much of the general population. The new structure explicitly denied the authority of the pope in ways that fuelled fears of a secret anti-religious (possibly Protestant, Masonic, Jewish) agenda behind the whole Revolution. Many priests scorned such views, seeing a church which was renewed and cleansed of plutocratic excesses. But many others clung to them, as parishioners clung to actual churches now threatened with closure through structural rationalisation and to the educational and charitable services of monks and nuns. Riotous protest, amounting almost to insurrection in some regions, increased and meshed too easily with groups of real counter-revolutionary agents.

Rural discontent in general rose through the second half of 1790 as the population absorbed the news that legislation demanded they ‘redeem’ their feudal dues at great cost and in some regions peasants had to endure landlords lumping abolished tithes into their rents. This was sanctioned by the National Assembly, presumably believing that money left in the hands of peasants would be wasted. While this helped to aggravate the rising levels of protest around religion, in the cities revolutionary leaders also faced growing radical pressure, as club organisation spread from the prosperous ranks of Jacobins down to more ‘popular societies’, with low subscriptions and mixed-sex membership. In Paris and Lyon in particular, networks of clubs grew up that saw the shadow of counter-revolution in everything that was not uncompromisingly anti-aristocratic and made this known vehemently in the press and in public demonstrations.

Two events in 1791 shattered the idea of a swift final resolution to the constitutional travails of the country. In January almost half of all priests refused to take a loyalty oath, imposed to try to end dissent over the Civil Constitution. In some regions, notably the north-west, refusal ran at over 80 per cent. ‘Non-juring’ priests became a new category of revolutionary enemy and a dissident ‘refractory’ church now competed openly for popular loyalties with the ‘constitutional’ clergy appointed to replace them. Violence accompanied the split everywhere – priests, old and new, were dragged from pulpits, a few were even shot at, while in Paris furious crowds inflicted humiliating beatings on nuns, with salacious press commentary. As with every other problem of public life – notably rising inflation in the assignat paper currency introduced on the collateral of the church’s lands – counter-revolution was blamed automatically for this situation and actual counter-revolutionaries strove to take advantage of it (see Gemma Betros for an overview of this critical issue).

***

At the very top of politics, the religious crisis engaged the conscience of the king, who tried to avoid Easter communion with a constitutional priest by leaving the city but was blockaded by a huge crowd. This confirmed the royal couple in the plans they were already making for escape and on the night of June 20th they fled the city with their children, heading for the eastern frontier garrisons and their loyal officers. Louis left behind a comprehensive written denunciation of the Revolution and all its works, showing without a doubt that the constitutional monarchy the Assembly had hoped it was crafting was a hollow sham.

Louis XVI and his family, dressed as bourgeois, arrested in Varennes

Louis XVI and his family, dressed as bourgeois, arrested in Varennes

The royal coach was stopped at the small town that gives this episode its name: the Flight to Varennes. The humble town councillors could not be browbeaten into letting the king and queen pass and, over the next day, thousands of locals rallied to defend against a possible counter-revolutionary armed incursion. Escorted back to Paris in a massive paramilitary procession, harangued by local officials about patriotism at every stop, they were stripped of any illusion that the ‘real’ France, outside the capital they detested, was still royalist. Rather than a change of heart, this occasioned more plotting, as they agreed with the desperate leadership of the Assembly to go along with the fairy story that they had been kidnapped and to accept Louis’ constitutional role, while secretly agitating for a foreign invasion.

Reactions to the Flight crystallised the growing tension between revolutionaries and the elite. The Jacobin Club split, with most of its members within the Assembly accepting the royal compromise and many outside demanding a popular voice in the decision. The latter managed to hang onto the identity and legitimacy of Jacobins, while the former started a breakaway ‘Feuillant’ club that remained a relatively closed circle of politicians. Meanwhile, the wider Parisian club movement tried to launch a mass petition for a referendum on the king’s position. With tension high in the city and a continued belief amongst the elite in ‘disorganisers’ and ‘anarchists’ as a rowdy front for counter-revolutionary brigandage, martial law was declared and the National Guard militia opened fire on the crowd in the ‘Champ de Mars Massacre’. Some radical leaders were arrested and others went into hiding.

***

The culmination of the work of the National Assembly was thus marked, first with blood and threats of legal persecution and then with weeks in which new restrictive laws on public meetings and popular activism were added to the constitutional edifice in a desperate effort to shore it up. Although a general amnesty for political offences was passed to celebrate its completion and a wave of relief-tinged joy swept the country upon the king’s acceptance of it in September, the portents were gloomy. Louis, humiliated by deputies’ lack of respect at the ceremony in which he swore himself in, wept helplessly in front of his horrified family. Many others would have been horrified, too, if they had known that he had perjured himself and was working with the queen and the émigrés to bring about an ‘armed congress’ of European powers to free him from revolutionary shackles.

The agenda of the newly elected Legislative Assembly, that Feuillant leaders hoped to use to stabilise the country, soon instead became dominated by the continued echoes of the king’s flight. Radical Jacobins, led by the Parisian journalist Jacques-Pierre Brissot, and men who had risen through the politics of their local regions in the turbulent revolutionary years, presented an uncompromising challenge to the idea that the king, as head of the executive branch, would be allowed to peaceably set policy. It took less than two months to push him into vetoing measures against émigré nobles and refractory priests and by the end of the year the ‘Brissotins’ were actively calling for a war against the German powers sheltering the Revolution’s enemies.

Maximilien Robespierre, who had built a reputation as an ‘incorruptible’ spokesman for the oppressed people in the National Assembly, was in these months almost a lone voice warning of the dangers of war. Where Brissotins asserted the invincibility of free men in combat against the ‘slaves’ of tyranny, he saw an unprepared nation being hurried towards a death-trap. As more conservative figures came around to the war agenda, seeking to use it to stamp authority on the turbulent people, and as the royal couple and their allies increasingly plotted to use war to bring the Revolution down, Robespierre’s suspicions were all too well-founded. The drumbeat of hostilities became irresistible, however, and on April 20th France declared war on Austria, the leader, under the Habsburg emperor, of the Holy Roman Empire.

The period of the spring and early summer of 1792 was a turning point for future politics, beyond the simple, albeit critical, fact of movement from peace to war. The Brissotins in the Assembly had been seeking not merely influence for their views, but power, and specifically to install their friends as royal ministers. They succeeded in this a month before the declaration of war, but this meant that they took the blame from forces to their left as the war proved to go very badly. Robespierre’s analysis, that there was some nefarious intent beneath their martial ardour, gained currency especially with the Parisian local Sections. In these neighbourhood committees, some were increasingly accepting the newly minted identity of ‘sans-culottes’: radical popular patriots, not the ‘friends of the people’ the Brissotins claimed to be, but the people themselves.

Through May and June, as French armies failed to make advances and the unthinkable prospect of an enemy invasion loomed, Brissotins both assailed the sinister influence of an ‘Austrian Committee’ inside the Court and called for more decisive royal action. The Assembly produced further emergency measures but ministers despaired as Louis refused to sanction them. In mid-June the Brissotin ministers were dismissed after openly warning that the king was heading down a disastrous path, but their supporters in the Assembly continued to harass their Feuillant successors (see MJ Sydenham for a further traumatic episode when the king was confronted by protesters in his own palace). By early July, with Prussia entering the war, the Assembly was driven to create and enact a measure to declare ‘The Fatherland in Danger’, mobilising the National Guard and taking powers to override the royal veto – powers which, having never been formally sanctioned by the king, were unconstitutional in their essence.

In the second half of July, with ardently patriotic militiamen from around the country beginning to gather in the capital as a fédéré force for its defence, the Brissotin leadership sought desperately to stabilise the situation. Fatally for its political future, it negotiated secretly with the king for a return to power, while publicly warning of the risks of a decisive move against Louis. This would damn it forever in more radical eyes. Momentum among the sans-culottes and the fédérés for action was rising, especially after word that the enemy’s ‘Brunswick Manifesto’ had threatened to raze Paris, if the king were harmed. On August 9th, the Assembly refused to rule on Parisian petitions to topple the king and on that same day forces in the capital formed an ‘Insurrectional Commune’, which on August 10th ordered an advance by several columns of National Guards on the Tuileries Palace.

***

The king, primarily concerned for his family’s safety, surrendered into the custody of the Legislative Assembly before any overt confrontation, but his garrison of Swiss Guards, left behind without orders, refused Parisians’ demands to lay down their arms. Someone fired a first shot and a battle erupted that turned into a slaughter. Some 300 insurgents were shot down but the Swiss were overwhelmed, with hundreds killed on the spot and dozens more hunted down and butchered as they tried to flee through neighbouring streets. Crowds invaded the palace, hauling out royal finery to burn in massive bonfires. The Assembly decreed the king ‘suspended’, but in truth the monarchy had clearly been toppled.

The Seizing of the Tuileries Palace by Jean Duplessis-BertauxThat fact was reinforced by the purge of the administration that followed: in many ways more rapid and decisive than the changes of 1789, which had often left old authorities effectively intact for months. Now royalists of every stripe were driven from office and many found themselves in custody. In Paris, the prisons swelled with hundreds of new suspects and a new tribunal began work a week after the Tuileries events, sentencing some of the more egregious counter-revolutionaries to death. This was not fast enough for many local sans-culottes: politicians and press warned of catastrophic subversion in the city as enemy armies drew near, besieging Verdun, the last fortress before the capital, at the start of September. Between September 2nd and 5th, in the region of 1,500 people were killed in the Parisian prisons in what almost all revolutionary observers at the time agreed was a regrettable necessity. The great majority of those killed were ordinary criminals, defined as ‘brigands’ available for aristocratic subversion; the rest were a selection of those priests, nobles and officials recently rounded up.

The Seizing of the Tuileries Palace by Jean Duplessis-BertauxThat fact was reinforced by the purge of the administration that followed: in many ways more rapid and decisive than the changes of 1789, which had often left old authorities effectively intact for months. Now royalists of every stripe were driven from office and many found themselves in custody. In Paris, the prisons swelled with hundreds of new suspects and a new tribunal began work a week after the Tuileries events, sentencing some of the more egregious counter-revolutionaries to death. This was not fast enough for many local sans-culottes: politicians and press warned of catastrophic subversion in the city as enemy armies drew near, besieging Verdun, the last fortress before the capital, at the start of September. Between September 2nd and 5th, in the region of 1,500 people were killed in the Parisian prisons in what almost all revolutionary observers at the time agreed was a regrettable necessity. The great majority of those killed were ordinary criminals, defined as ‘brigands’ available for aristocratic subversion; the rest were a selection of those priests, nobles and officials recently rounded up.

It is important to recognise the selective element in these ‘September Massacres’. They became the iconic moment of popular savagery in counter-revolutionary retellings and for Brissotins, who came to believe Robespierre had tried to dispose of their leaders through them. But most ‘counter-revolutionary’ prisoners survived the massacres, having had their case files reviewed and sometimes having been questioned for hours by ad-hoc tribunals in each prison. The princesse de Lamballe, Marie Antoinette’s favourite, was indeed decapitated but did not suffer the sexual mutilations of many accounts and was almost the only woman to die. There is very little truly contemporary evidence for the many scenes of sadism later alleged to have taken place – it is true that victims were mostly hacked to death in very bloody processes but accounts of actual torture from immediate witnesses are essentially absent.

In a society that recoils from all face-to-face violence, it may seem odd to insist on a distinction between grim and gruesome killings and acts of popular savagery and sadism, but grim and gruesome public execution was an 18th-century norm (one which, indeed, the Revolution itself had only just toned down to ‘painless’ decapitation). Stories of the September Massacres were used, consciously and persistently, to paint their perpetrators as subhuman monsters of perversion, when they seem, mostly, to have been men grimly committed to a bloody solution to a clear problem of political and military survival.

Less than three weeks later the Revolution’s forces stemmed the enemy tide at the Battle of Valmy and began an advance that would see them largely overrunning modern-day Belgium by the winter, and occupying the Rhineland in the east. From the perspective of patriots on the ground, what had happened in Paris was part and parcel of the effort required to move from disaster under the monarchy to apparent stunning triumph. The first meeting of the hastily elected National Convention had been on the day of Valmy and, two days later, on September 22nd, it had proclaimed France a Republic. Within only a few more days, Brissotins in the new body had called for a new fédéré force to protect them, not from aristocrats but from the overweening power of the Parisian sans-culottes, and had accused Robespierre of aspiring to dictatorship. Moments of genuine unity in revolutionary politics were rare and fleeting (see Marisa Linton on how Robespierre navigated revolutionary politics).

***

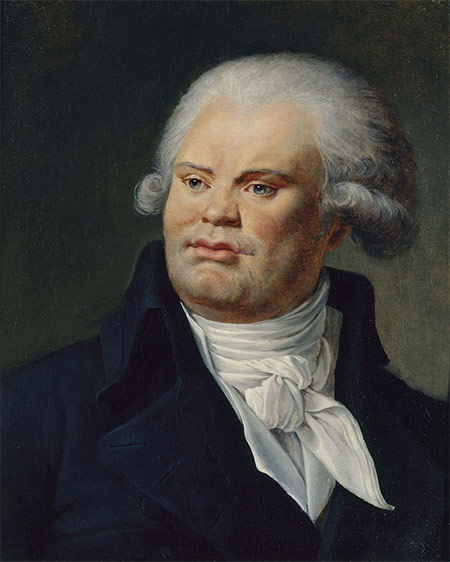

The evolution of events and structures that have come to be called ‘the Terror’ was firmly embedded in both the external warfare and internal strife already locked in place. Brissotins, now also labelled as ‘Girondins’ after several leading speakers from the Gironde department around Bordeaux, continually clashed with the more radical contingent that included Robespierre, the incendiary journalist Jean-Paul Marat and the stentorian orator Georges-Jacques Danton. This other group were nicknamed the Mountain, or Montagnards; their habit of sitting on the highest benches on the left of the chamber overlapping with a key Enlightenment notion of the purity and virtues of alpine landscapes and peoples. Ironically, the Girondins probably had a stronger claim to being the heirs of Enlightenment, some of them holding strongly advanced views on slavery, women’s rights and democracy, but they had already proved themselves to be disastrously inept politicians and this pattern continued (see Stuart Andrews for more on the Girondins’ intellectual and international connections).

Girondins and Montagnards spent the remainder of 1792 at loggerheads about the trial of the king: unanimity about his guilt did not prevent violent dispute about whether he should be executed, in debates which continuously reinforced the fear that opponents were secret counter-revolutionary ‘disorganisers’. The National Convention was split nearly down the middle by a series of votes in January 1793 before the king went to his death in sombre dignity on the 21st (see William Doyle for the complex tale of Louis’s decline and fall). By early March, the violence of debate had turned to violence on the streets, as Girondin-leaning newspapers had their offices invaded and presses smashed by radical sans-culotte activists. By April, Girondins had persuaded the Convention to start a crackdown – impeaching Marat for an incendiary circular to Jacobin clubs, only to see him acquitted by the newly-founded Revolutionary Tribunal. In May they tried again, forming a ‘Commission of Twelve’, charged with rooting out dangerous subversives in the sans-culotte movement.

All this was happening at the same time as the Convention strove to manage an expanding and increasingly critical military situation. France chose to extend the war to the Netherlands, Britain and the Italian states in the late winter, rounding off by adding Spain on March 7th, ensuring that armies were needed for every land frontier, and facing immediate naval blockade. This was done in the belief that the crowned heads of Europe were already in coalition against them, matched by the incorporation of conquered Belgian territories into the nation and the annexation of Monaco and Basle. Sustaining this aggressive posture was cripplingly difficult.

***

The victories of late 1792 had been won with an army that was a chaotic mixture of old regular units and volunteers mobilised for national defence. Many of the latter had only signed up for one campaign and, in the harsh conditions of a winter in the field, a large number packed up and went home, seeing their duty done. The Convention acted in February 1793 to amalgamate old and new military units on a consistent basis and to order the levy, by local quotas, of an extra 300,000 men for immediate service. Not strictly individual conscription, this was nonetheless greeted with outrage in regions already alienated by revolutionary religious policy. Large areas of the south and of Brittany and Normandy were disturbed, with rural protests and occasional direct attacks on authority. In the Vendée region of the lower Loire valley to the south of Brittany, a more concentrated insurrection erupted, becoming within weeks a large ‘Royal and Catholic Army’ which threatened to destabilise the entire region, spreading gruesome tales of massacre as it did so.

News of this hovered over the Convention in the next few weeks, as it established the Revolutionary Tribunal to judge counter-revolution, decreed the death-penalty for a range of subversive offences, set up surveillance committees in every community, extended press censorship and created a system of Representatives on Mission, sending its own members out to directly monitor the war-effort, all co-ordinated by a new, compact, Committee of Public Safety, set up in April. Further dread news had arrived in March after a bold advance into the Netherlands had met defeat from resurgent Austrian troops at Neerwinden on the 18th. Military confidence was shattered and the French armies began a dramatic and chaotic evacuation of the Belgian territories formally declared part of France only weeks earlier. The machinery of ‘the Terror’ was thus erected in conditions of looming catastrophic defeat.

The final link in a chain of disaster was made when the defeated French commander, Dumouriez, ally and former cabinet colleague of the Girondin leadership, tried to draw his Austrian counterparts into negotiations for him to use his armies to restore pro-Girondin order in Paris. Staggeringly implausible, this scheme nonetheless saw him handing over several emissaries from the Convention to the enemy, before himself fleeing to their custody on April 5th. Echoing as it did a similar plot in which the former revolutionary hero Lafayette had fled shortly after the fall of the monarchy, it bound the Girondins, in radical eyes, into a fixed pattern of hideous treason (See Esmond Wright on Lafayette’s rise and fall).

Their efforts to strike back against the sans-culotte leadership in Paris were thus coloured by this dreadful and inflammatory context as not merely tyrannical, but definitively counter-revolutionary.

***

The logic of unfolding conflict played out to its next level in May 1793. Girondins and Montagnards had been competing for support not just in Paris, but nationwide, with their own networks of correspondence, powerbases in local government and club memberships. Both sides blasted the other as counter-revolutionary, with Girondins regularly depicted as plutocrats and Montagnards and sans-culottes as unprincipled opportunistic looters (though in reality the social distinction between them in was nowhere near this clear-cut). In the last week of May, effectively simultaneously, Girondin forces rose against the leadership of Montagnards in Marseille and Lyon, while the Parisian sans-culotte movement used its powerbase in the city’s municipal government to co-ordinate an armed siege of the Convention.

Twenty-nine Girondins were expelled from the Convention on June 2nd and detained under house arrest along with two ministers. Many of them succeeded in fleeing, finding further sympathisers in Normandy and Bordeaux. Thus, by the early summer of 1793, France faced war on every frontier, an overtly counter-revolutionary internal enemy in the west and a civil war between republicans in three major regions. Those who remained loyal to the Convention shared, very clearly, the blame for bringing about this situation, but nonetheless, it was for them now a matter of survival and the continued ramping-up of ‘Terror’ took place in that light.

Although for a few weeks there were efforts to persuade pro-Girondin localities to reconcile with Paris, by the second half of the summer those ‘Federalist’ rebels who persisted were being demonised as firmly as any other enemies. Charlotte Corday’s act of lone heroism on July 13th, believing she could end the conflict by assassinating Marat, cemented instead the notion of an insidious foe. Though the Convention finished drafting a new democratic constitution in late June, and celebrated its ratification on the first anniversary of the fall of the monarchy, raging civil war provided a solid argument for continuing the undivided revolutionary rule of the Convention (something affirmed definitively ‘until the peace’ in October).

New revolutionary measures were piled up, under notable pressure from Parisian sans-culottes. Both a ‘Mass Levy’ of economic and military mobilisation in late August and a series of measures against ‘suspects’ came in after direct intervention from demonstrating crowds. While some agendas such as these seemed to create greater unity, others began to pull apart even the already narrow bounds of patriotic tolerance. Robespierre, who had joined the Committee of Public Safety in late July, found himself forced to advocate against both new elections and the persecution of a widening circle of Girondin sympathisers: while some two dozen Girondin leaders were guillotined in the autumn, over 70 more deputies were held in prison, but survived the Terror.

If some were saved, the logic of republican retribution nonetheless struck out in multiple directions – radical women’s societies were banned, as Montagnard misogyny led to the executions of Marie Antoinette and Madame Roland alongside the writer Olympe de Gouges and the former royal mistress Madame du Barry (see Olwen Hufton for more on how revolutionary politics raised and dashed women’s hopes). Among the most radical men, hatred of the Church and Catholicism’s place in fuelling revolt transmuted into an atheism both philosophical and brutally satirical and often itself misogynistic in its denunciation of ‘priest-ridden’ women and their folly. Some Representatives on Mission proscribed religious ceremonies and secularised burials, while others connived at public mockery of religious vestments and ceremonies, and harassed priests into renouncing their vocations. Through the autumn and winter of 1793 such activity reached a crescendo, as a peak of local initiative, labelled retrospectively as the ‘anarchic Terror’, coincided with the most critical phases of the war being levied against rebels in the Vendée and Federalist regions. Even as those wars were being won, the spiralling logic of betrayal already established since 1789 was eating away at politics again.

While republicans created a panoply of new unifying cultural symbols – changing the calendar in the autumn of 1793, inventing a new religion of the ‘Supreme Being’ in the spring – they could not stop elevating their differences into divisions (see Matthew Shaw on the heritage of the ‘republican calendar’). Already by the end of 1793, advocates for magnanimity in victory clashed with campaigners against compromise and both sniped at the Committee of Public Safety in ways which seemed to imperil further progress. To the overt clash of perspectives was added a fog of more-or-less private and whispered accusations of corruption, with a further blurring of lines between odious self-enrichment and profiting from counter-revolution.

The first seven months of 1794 saw revolutionary triumph become unmitigated horror. Victory over the Federalists and the Vendée, secured on the battlefield at the end of 1793, was turned into massacre. Rebels captured under arms were marked for death by a decree of March 1793, but this was extended to the butchery of whole communities by ‘infernal columns’ in the West, and to a savage combing-out of victims from subjugated populations in the southeast. Any sign of weakness by those leading such actions was met with harassing decrees from Paris, leading to recall under the shadow of suspicion. In a mark of increasingly obsessional puritanism, those who had overstepped some notional limit of stern probity in their bloody rigour were also made to feel under threat. As military victories against external foes accumulated by the summer, the internal pressure did not slacken. Those who walked this fine line did so by accelerating the pace of executions. In June the Revolutionary Tribunal in Paris had its procedure streamlined as ruthlessly as a production-line (although it still produced a significant minority of acquittals, even in these fervid months).

This could not last and it did not. At the end of July, on the revolutionary date of 9 Thermidor, the Convention, threatened overtly the previous day by Robespierre with a massive new purge, almost unanimously threw the blame for everything that had been happening onto him and his close circle of acolytes. It was a move that did not so much reverse the logic of the previous years, as accelerate it: the traitors and tyrants were revealed at last to be at the very pinnacle of power, hiding in plain sight under the mantle of the purest and most incorruptible patriotism. Rooting out the ‘Robespierrists’ and guillotining a hundred of them in the coming days was an act entirely in keeping with the logic of the past four years, as was the charge that Robespierre, a man of irreproachable private morality, had sought to marry Louis XVI’s imprisoned teenage daughter and make himself king (see Colin Jones for more on the mythologies of Thermidor).

***

What happened after 9 Thermidor has commonly been labelled a ‘reaction’. In classic Marxist accounts this term clearly indicated that the advance of a popular agenda, embracing the working classes, died with Robespierre. More recent historiography has identified the sizeable gulf between the vision of society emerging from Robespierre’s circle of puritanical devotees, and any real attention to ‘popular’ social or economic needs. Workers under the Terror were strictly regulated and any measures for their wellbeing were highly paternalist and dependent on their continued compliance. The sans-culotte movement had been crushed by the Committee of Public Safety months earlier and, in any case, its leadership, under closer scrutiny, was far from uniformly plebeian: Robespierre had accused many of them of wearing a popular identity like a pantomime costume. The General Maximum, seen by urban populations as a decisive lifeline for their survival as consumers, was detested cordially by almost all in the Convention, while the Robespierrists themselves had introduced dramatically unpopular controls on wages days before their fall.

Most of those who led the thermidorian overthrow saw themselves as saving the Revolution from a tyrant and most of them were, by any reasonable definition, as complicit in the wider Terror as Robespierre himself. But in order to secure their own survival, they did have to back away from the direction events had been taking and, in that broader sense, a political reaction was exactly what followed. This led on to a definite rightward movement and a social turn against the popular classes, stigmatised and scapegoated as the source of ‘terrorist’ violence.

The Convention liberated many detained suspects in the late summer of 1794 and the flooding back into public life of people who were, on the whole, richer and more right-wing than average had an inevitable effect. So too did the restoration to their Convention seats of Girondin sympathisers, who began to ramp up demands for wider vengeance on those who had condemned them. Revocation of the General Maximum in the depths of a ferocious winter followed, as sympathy for the poor evaporated. When in the following spring desperate Parisians raised the banner of the sans-culottes in a series of doomed insurrections, it was the perfect excuse for the Convention to purge its own membership of radical Montagnards, and start a national campaign of harassment and denigration of popular activists.

In all this, the Convention nonetheless also confronted royalism, especially when in June 1795 Louis XVI’s son died in Parisian captivity, and the Comte de Provence, in emigration since 1791, declared himself Louis XVIII, intransigently committed to a full restoration of the Old Regime. This came in the midst of months of ‘White Terror’ as royalist factions, especially in south-eastern France, took bloody revenge on local Jacobins (often dragging them from the prison cells where they had been put by thermidorian authorities). When the Convention voted a measure to ensure its own members dominated the new constitutional legislature, it was, at last, creating a threatening royalist insurrection in Paris. This was seen off by a young General Bonaparte, who christened the new Directorial regime with a ‘whiff of grapeshot’.

If revolutionary politics before thermidor had been a seemingly-inevitable spiral of betrayal and accelerating conflict, those after it settled into a no less apparently inescapable pattern of cyclical repetition. Nearly every year down to 1799 saw at least one royalist or Jacobin plot broken up, at least one violent change of policy from the ‘extreme centrists’ in power who lashed out to left and right, currying temporary favour with one side until they seemed too powerful, then swinging the other way (see WJ Fishman for the most famous of the radical plotters). Elections were an annual ritual, but from 1797 they were also a process of fudging the results, claiming corruption, and barring hundreds of successful candidates from office. The economy was more or less in chaos, the currency undergoing hyperinflation and the state sustained by the fact that, despite political mayhem, the mass-mobilisation of 1793/94 had created a huge, and apparently all-conquering, army, that could loot France’s neighbours at will.

The paradox of the later 1790s was the rebuilding of a strong state out of a chaotic society, when that chaos had been caused by the unleashing of unlimited state power in the previous years. It was accomplished by a ruthless reassertion of power by men at the pinnacle of Parisian affairs, agreeing to ignore the question of how they had got there and focus on securing themselves as the elite leadership of what they increasingly labelled as the ‘Great Nation’. The scope of their ambition was marked by the despatch in 1798 of Bonaparte to conquer Egypt and perhaps tilt the balance of global imperial power, while bearing with him shiploads of savants to turn their scientific gaze on deciphering and cataloguing the mysteries of ancient civilisation. When that proved to be an overstretch, and resurgent enemies threw French power out of Italy in 1799, setting internal politics aflame again with insurrections and plots, the elite decided to abandon the pretence of democracy in the interests of self-preservation. Bonaparte fled Egypt in time to join the plotters (though he was not their first choice for a figurehead) and the rest is another history (see Gemma Betros on the enigmatic man at the heart of it).

David Andress is Professor of Modern History at the University of Portsmouth.

Adaugă un comentariu

© 2024 Created by altmarius.

Oferit de

![]()

Embleme | Raportare eroare | Termeni de utilizare a serviciilor

Pentru a putea adăuga comentarii trebuie să fii membru al altmarius !

Alătură-te reţelei altmarius