cultură şi spiritualitate

Islam’s Forgotten Scholars

http://www.historytoday.com/arezou-azad/islam%E2%80%99s-forgotten-s...

The Islamic world produced some of the greatest minds of the Middle Ages, including a number of remarkable female scholars. Arezou Azad examines who these women were and why their place in history has been neglected.

Poetry has a prominent place in Islamic society and the Persianate world. Though people across the Islamic world spoke multiple dialects and languages, Persian served as the language for some of the finest verses of the Middle Ages, created by poets such as Hafiz, Rumi and Nizami. It was the scholar-mystic Jamal al-Din Nizami who produced the verse that described the first encounter between the two protagonists in the epic poem, Leili and Majnun.

Leili and Majnun are the quintessentially ill-fated lovers, celebrated in Persian and Arabic medieval poetry. Their story was perfected by Nizami, who lived in Ganja in today’s Azerbaijan, in the latter half of the 12th century. Many variants of the story are familiar across cultures, thanks to its dogged survival over the centuries: two people fall in love in a forbidding society, separated (yet unbroken) by the social conventions of blood and class. Whether Leili and Majnun were the Muslim Romeo and Juliet, or stood for the abstract Sufi principles of mystical love (mahabba) and fellowship with God (uns) as some scholars have claimed, there is at least one aspect of their encounter that is understated: the couple first met at school.

The exact origins of the story of Leili and Majnun are not known, but we can trace it back at least to pre-Islamic Arabia, that is, before the early seventh century. Six centuries later, when Nizami wrote his poem, he retained the context of a mixed school for his story and the manuscript illustrators in 15th- and 16th-century Herat in Afghanistan painted the school classroom as it must have looked in their time. The evidence shows that medieval Muslim boys and girls studied together in full view of one another. This contrasts sharply with what one might expect from ‘medieval’ Islam, where the term is assumed to be synonymous with ‘backward’ and ‘old-fashioned’. Yet scholars in medieval Europe demonstrate that the ‘medieval’ could often be considerably more humane and pluralistic than the ‘contemporary’.

Do we, then, find a similarly enlightened attitude towards women and education in medieval Islamic texts? Limiting ourselves to Nizami’s descriptions of primary school education is perhaps setting the bar too low, especially knowing as we do that women attained the highest standards of medieval Islamic knowledge. The historian Jonathan Berkey, for example, counts 411 women out of a collection of more than 1,000 15th-century scholars listed in an Egyptian biographical compilation of the time. These women often received licenses, or ijazas (roughly equivalent to a PhD today), to transmit their knowledge on all manner of subjects. The numbers increase if we count the biographies of women embedded within the biographies of their husbands or other male family members, such as fathers and brothers, which have been counted by the historian Ruth Roded and her team.

Young women gazing at Kabul from its hills, c.2014.

Young women gazing at Kabul from its hills, c.2014.

As an example, in one of the first Islamic biographical collections, the ninth-century compilation Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kubra (Book of the Major Classes) by the Iraqi scholar Ibn Sa’d, there are 629 entries on female scholars, but the number increases to 4,250 when we include the women mentioned in the biographies of their male relatives and husbands. The proportion of medieval women scholars may reach as much as a quarter of the scholarly community. It is a fascinating and striking figure that shouts in the face of the popular rhetoric on the supposed ‘silence’ of women in medieval Islam.

If we break down the numbers, we find that the largest group of women scholars flourished in the very early years of Islam, in the time of Muhammad (d.632). It can be said that the prophet literally surrounded himself with strong and intelligent women. The numbers remain high until about the ninth century, when they drop, only to rise again briefly in the 15th and 16th centuries. How do we explain this rollercoaster trend? Do the numbers indicate an actual decline in educational figures, or were women later written out of history by male chroniclers? The latter argument is popular among feminist social scientists, who pay little attention to historical detail, although there is probably some truth to it. Equally, we have evidence that dozens of elite women wielded inordinate levels of power in the Abbasid royal court and in the offices of provincial governors during the eighth and ninth centuries.

One such woman was described in the late 12th-century local chronicle called the Merits of Balkh (Fada’il-i Balkh), written by Abu Bakr Abdullah al-Wa’iz al-Balkhi. We learn that she became the de facto governor of Balkh (in Afghanistan), a large territory that included around 20 towns and substantial rural estates reminiscent of medieval European principalities. Although she remains unnamed and is only identified as Davud’s khatun (‘lady’), we learn that her husband Davud (the Muslim rendition of the name David) belonged to a powerful local family known as the Banijurids. We are told that in the year 848 her husband was appointed as the governor of Balkh, but in the subsquent 20 years of his rule he seems to have become obsessed with the construction of a pleasure palace and surrounding complex for himself which he called Nawshād (‘New Joy’). She assumed the governorship ‘so that she should take particular responsibility for the city and people’. While much has been made of the misogynistic statements on the non-compatibility of women and politics in early Islamic texts, such as the administrative manual written by the 11th-century Iraqi scholar al-Mawardi (he explicitly states that a ruler ‘may not be a woman, hermaphrodite, a mute, or a person with a lisp’), the account of this woman in the Merits of Balkh is nothing but complimentary:

Some historians have said the caliphal court demanded land tax [kharaj] more than was necessary. The khatun of Davud sent by the hand of the caliphal tax collector her jewels, and they say that the jewels were stitched into her garments of pearls and rubies. She said: ‘This garment has been sent so that they do not demand more grain of kharaj than farmers can reap.’ When the tax collector arrived at the caliph’s court with that garment and related the whole story to the caliph, the latter exempted Balkh from paying its kharaj for that year. He returned the garment, and said: ‘This khatun has taught us gentlemanliness and generosity, and we are ashamed to take her garment.’ When they brought those jewels back to Balkh, the khatun said: ‘I presented these jewels as a gift to the Muslims and inhabitants of Balkh, and I am not taking them back.’ They used them for the building of the congregational mosque and the town’s water canal, and still the pleats and sleeves were left over.

Here we have an example of a just, generous, charitable and dignified ruler. The author would have seen such qualities outlined in the ‘mirrors for princes’ (a type of textbook for rulers), which were in circulation throughout the medieval Islamic world and which find their counterparts among the medieval European Fürstenspiegel, of which Machiavelli’s The Prince is the most famous. This particular anecdote refers to a policy adopted by numerous caliphates, who gave local governors responsibility for tax collection in order to make up for the loss of provincial revenues and pay for their inflated bureaucracy. It was an exploitative practice, which this woman – unlike many of her male counterparts – was unwilling to support. The author is clearly in awe of her courage and perseverance; he even quotes the caliph as ascribing the quality of gentlemanliness to her, a characteristic usually thought of as inherently male.

Non-elite women also appeared in the public domain. Although we have far less historical evidence on them, some historians have unearthed and analysed their economic roles and impact. For example, we know that Syrian women in the 14th century and Iranian women in the 16th century worked in an array of occupational fields and disciplines, besides administration and academia, including hairdressing, selling at markets and engaging in tax-paying prostitution. Much more study is needed of the ancient texts to bring into sharper focus the contributions made by medieval Muslim women to their economies and societies, beyond looking after hearth and home. Only then can we understand whether these cases are exceptions to a general rule, or whether women were making consistently large contributions to the medieval economies of which they were a part.

Muhammad and his wives. Turkish miniature, 18th century

Muhammad and his wives. Turkish miniature, 18th century

Putting the numbers aside, what sort of image do scholarly women have in the sources? There is clearly a preponderance of one particular image, namely that of the saintly figure, marked by her unrelenting chastity and devotion to God. She rejects all material possessions and opts for a life of poverty. It is worth mentioning that, despite her relative meekness, this image of the female mystic – exemplified by the ninth-century Iraqi woman Rabi’a al-Adawiyya – still has a public role as a teacher and mentor to her many disciples, both male and female. This contrasts starkly with the image of the female mystic in medieval Europe, who had no public role and, in extreme cases, was even locked away for good in a monastery in order to devote herself entirely to her studies and prayers.

***

But the image of the Muslim spiritual woman who is chaste, charitable and poor is a simplistic one: were all women scholars like her? Our accounts on Rabi’a were written many centuries after her life, so whose interpretation do they represent and how reliable are they? It is almost impossible to trace the genealogy of the accounts on Rabi’a, but we can look for comparisons with other women. I recently came across a story of one ninth-century scholar called Fatima and nicknamed Umm Ali (the mother of Ali) who does not match the Rabi’a image. Umm Ali was from an élite class in Afghanistan’s Balkh. This was the ancient Bactra, which was conquered by Alexander the Great in the fourth century bc and is where he married his Sogdian wife Roxelana. It was captured by Muslims in the early eighth century, who wrested control of it from the Buddhists who had run the city and its centrepiece, the Naw Bahar Buddhist temple and monastery, which was visited and written about by Chinese Buddhist pilgrims and envoys from the T’ang court. Balkh, an important crossing point along the so-called Silk Road networks, was a melting pot of people from different countries, professing a variety of faiths, including Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Jainism, Judaism, Christianity and a set of local cults. By Umm Ali’s time, a century after the conquest, Balkh had become the qubbat al-Islam, the dome of Islam, and the umm al-bilad, the mother of all cities. Balkh was now no longer a place of learning for Buddhist scriptures but a centre for the interpretation of Islamic teachings. Whether there was a direct transmission of scholastic methods from the Buddhist to the Islamic is still a matter of speculation, although I suspect that some would necessarily have happened, if only inadvertently, through the simple fact that the Arab Muslim rulers hired local administrators. In fact, Balkh was home to the most famous of all local convert families, the Barmakids, who transformed themselves from the keepers of the Naw Bahar Buddhist complex to administrators for the caliph Harun al-Rashid in Baghdad himself. The Barmakid vizier (the equivalent of prime minister) has been immortalised in the Arabian Nights, whose main protagonist is Harun al-Rashid. (We know the story more for the fantastic tales that his slave-girl told the caliph in order to avoid execution.)

With this backdrop in mind, we can now imagine Umm Ali, described in three excerpts derived from a range of medieval texts:

She sent someone with a message to Ahmad that said: ‘Ask my father for my hand.’ Ahmad did not respond. She sent someone again with a message: ‘Oh Ahmad, I did not think you a man who would not follow the path of truth.’ Ahmad accepted and asked for her hand in marriage.

Umm Ali excused her husband of paying the later instalments of her bride-price on the condition that he marry her to the great spiritual scholar, Abu Yazid al-Bistami. He took her to Abu Yazid. She came before him and sat down in front of him, her face unveiled. Ahmad was amazed, and said to her: ‘I see that you are unveiled before Abu Yazid.’ She replied: ‘Because whenever I look at him I lose the fortune of my soul, and whenever I look at you I return to the fortunes of my soul.’ As he was leaving, Ahmad asked Abu Yazid for advice. The mystic said, ‘Learn chivalry from your wife!’

One day, an esteemed visitor arrived at Ahmad Khidrawayh’s house. Ahmad said to his wife: ‘I want you to invite this friend in because he is the lord of the generous and free’. She said: ‘Oh Ahmad! Can’t you do that, and don’t you know how one ought to invite these chivalrous people?’

These citations paint a picture of a ninth-century scholarly woman who first of all pursued her future husband with tenacity and wooed him for marriage. He eventually

conceded, presumably because she was a good catch, descending, unlike Ahmad, from a noble family. She married beneath her class, which is somewhat reminiscent of Muhammad’s first wife, Khadija, who was his employer’s daughter, much his senior in age and the main breadwinner of the family. The same sense of assertiveness can be gleaned from the third excerpt in which we learn that Umm Ali taught her husband the tricks of the trade on how to be a serious mystic (‘Oh Ahmad. Can’t you do that, and don’t you know...?’). She goes on to tell him the protocol for hosting mystical masters in one’s house, which involves the sacrifice of animals and the display of their carcasses

on the streets.

The second extract is curious because it implies that Umm Ali was married by her husband to another man, the mystic Abu Yazid. She also did not behave like a normal prospective bride, who would have lowered her veil, but instead removed it. Presumably this marriage would have been preceded by a divorce from Ahmad. Whether such a double marriage actually happened we cannot know, but it is interesting that the author of the excerpt, Abu Nu’aym al-Isfahani, who wrote in the early 11th century, felt it necessary to mention it. It may have been carried out in name only, to enable Umm Ali to be in close contact with another man. This sort of nominal marriage is reminiscent of the marriage carried out on the orders of Harun al-Rashid between his friend, the Barmakid Ja’far, and his sister Abbasa. The caliph reportedly engineered this nominal marriage so that he could enjoy the company of both his unmarried sister and his male friend together. To the caliph’s chagrin, however, Abbasa and Ja’far eventually consummated the marriage and the whole story ended badly. Either way, Umm Ali’s story involves a curious reference to a possible double marriage and it paints a very different picture of female sainthood from the better-known ultra-asceticism of Rab’a. Incidentally, certain kinds of ‘fictive marriages’ are still practised in Shi’ite Iran today as a way of enabling women and men to interact.

***

Umm Ali travelled extensively in her pursuit of knowledge. Women scholars in the Islamic east were held to the same exacting standards as their male counterparts. They had to travel the notorious routes westwards in order to study under the greatest masters of Islam. This took scholars to cities across vast expanses of the Eurasian continent. Mecca and Medina in the Arabian peninsula were obvious destinations as they were the homes of the prophet, but other centres of learning included Baghdad, Damascus, various north African cities and locations such as Rayy, near modern Tehran, and Nishapur in Iran. By the tenth century, Balkh, Bukhara and Samarkand, to the north in Uzbekistan, were added to this prestigious list.

Travel in the ninth century was not an easy matter. To go from Balkh to Mecca, for example, Umm Ali’s route to study with her teacher, Salih Abdullah al-Tirmidhi, meant covering thousands of miles of road, with many costly overnight stopovers at caravanserais (the lodgings of the medieval Islamic world, where travellers could seek rest). Only the wealthiest could afford to go on the hajj (the mandatory piligrimage to Mecca); fortunately, Umm Ali’s family had the money to do so. Her great-grandfather had been the first Arab governor of the region of Khurasan (‘the lands of the East’), to which Balkh belonged in the eighth century. Travel expenses included transport, food and lodging for the journeys, which totalled many weeks and months. She is alleged to have sold her estate for this purpose for 79,000 dirhams, which by all accounts was a substantial sum of money. Umm Ali stayed in Mecca for seven years to perfect her skill in reciting her master’s works, in order to then transmit them to her students and disciples upon her return to Balkh. This was the medieval system of ‘international’ transmission of knowledge. Paper had not yet been adopted outside China and even when it was, by the tenth century, it was vulnerable to fire, shipwrecks, theft and suchlike, so memorisation remained important to Islamic scholarship. It meant that Umm Ali had to live apart from her husband for this long amount of time as well. He was dead when she finally returned.

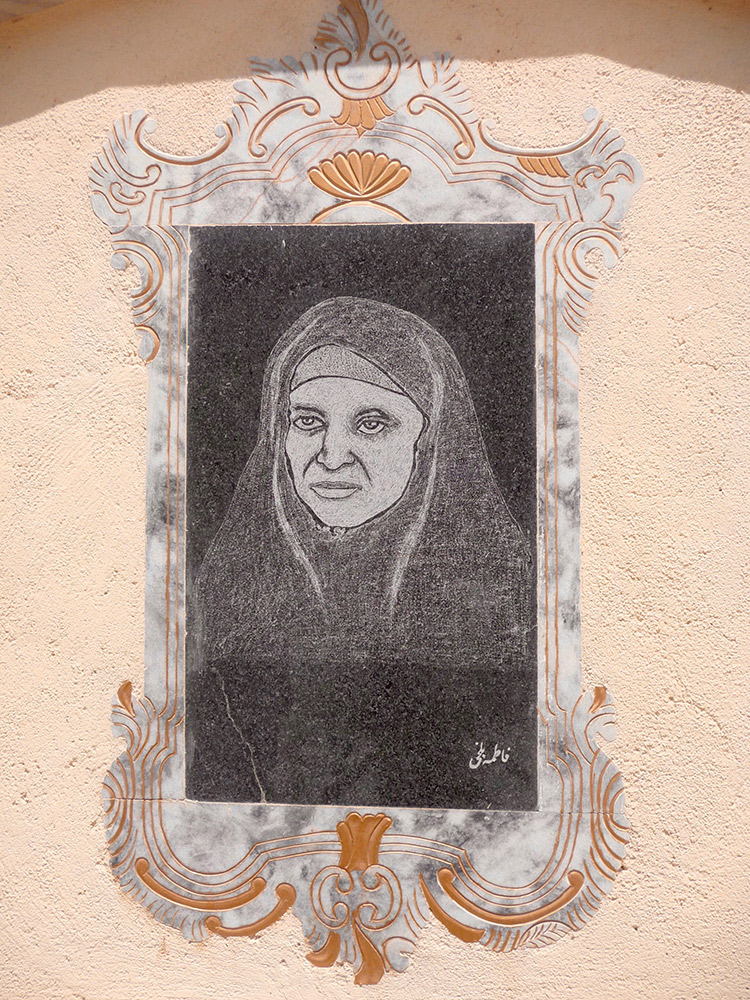

An image of Umm Ali, in Mazar-i-Sharif, 2009.

An image of Umm Ali, in Mazar-i-Sharif, 2009.

This is the image of Umm Ali that we can construct from contemporary sources, but her image has since changed. A later collection of biographies by the 15th-century scholar Jami transformed Umm Ali into a subservient and loyal wife who donated to the poor and ‘agreed with her husband on everything’.

This new portrayal appears to indicate that the author felt particularly compelled to embroider her biography, perhaps because the image of a woman who was superior to her husband was unpalatable to Jami’s circle. Gone are the allusions to her assertiveness. Gone is the suggestion that Umm Ali’s husband learned the tricks of the trade from her. And, in parallel, up rises Ahmad to become known as one of the forefathers of Sufism. (The term Sufism has not been used before now because this softer strand of Islam does not become a religious institution until the 15th century and later.) This is the version of Umm Ali that has stuck: an early modern narrative that makes her out to be less rough around the edges and subservient to her husband.

The context for this change is deserving of further study, but it is perhaps ironic that precisely during the period of the Enlightenment in 15th-century Europe the phenomenal prominence of women in the Islamic world wanes. The reasons for this trend are not yet understood, but will, no doubt, provide much fruitful ground for historians in future.

What we can take away from this study of female medieval Muslim scholars is that they were much more prevalent than has been thought previously and that they were part of a Muslim society in which gender parity found its expression in the public domain of work and education. It is well worth keeping this particular aspect of medieval history alive, because it provides an important counter to popular narratives in the media today on the limited role and agency of Muslim women. It is also a reminder that historical processes are not linear progressions; they take erratic and cyclical courses. It is worth pondering, too, that female medieval Islamic scholars had it better than one might expect, perhaps even better than today, and that the time may come when this trend is reversed yet again.

Arezou Azad is Lecturer in Medieval History at the University of Birmingham and the author of Sacred Landscape in Medieval Afghanistan (OUP, 2013).

STATISTICI

Numar de steaguri: 273

Record vizitatori: 8,782 (3.04.2011)

16,676 (3.04.2011)

Steaguri lipsa: 33

1 stat are peste 700,000 clickuri (Romania)

1 stat are peste 100.000 clickuri (USA)

1 stat are peste 50,000 clickuri (Moldova)

2 state au peste 20,000 clickuri (Italia, Germania)

4 state are peste 10.000 clickuri (Franta, Ungaria, Spania,, Marea Britanie,)

6 state au peste 5.000 clickuri (Olanda, Belgia, Canada, )

10 state au peste 1,000 clickuri (Polonia, Rusia, Australia, Irlanda, Israel, Grecia, Elvetia , Brazilia, Suedia, Austria)

50 state au peste 100 clickuri

20 state au un click

DE URMĂRIT

1.EDITURA HOFFMAN

https://www.editurahoffman.ro/

2. EDITURA ISTROS

https://www.muzeulbrailei.ro/editura-istros/

3.EDITURA UNIVERSITATII CUZA - IASI

https://www.editura.uaic.ro/produse/editura/ultimele-aparitii/1

4.ANTICARIAT UNU

https://www.anticariat-unu.ro/wishlist

5. PRINTRE CARTI

6. ANTICARIAT ALBERT

7. ANTICARIAT ODIN

8. TARGUL CARTII

9. ANTICARIAT PLUS

10. LIBRĂRIILE:NET

https://www.librariileonline.ro/carti/literatura--i1678?filtru=2-452

https://www.librarie.net/cautare-rezultate.php?&page=2&t=opere+fundamentale&sort=top

14. ANTICARIAT NOU

https://anticariatnou.wordpress.com/

15.OKAZII

https://www.okazii.ro/cart?step=0&tr_buyerid=6092150

16. ANTIKVARIUM.RO

17.ANTIKVARIUS.RO

18. ANTICARIAT URSU

https://anticariat-ursu.ro/index.php?route=common/home

19.EDITURA TEORA - UNIVERSITAS

20. EDITURA SPANDUGINO

21. FILATELIE

22 MAX

http://romanianstampnews.blogspot.com

23.LIBREX

https://www.librex.ro/search/editura+polirom/?q=editura+polirom

24. LIBMAG

https://www.libmag.ro/carti-la-preturi-sub-10-lei/filtre/edituri/polirom/

https://www.libris.ro/account/myWishlist

http://magiamuntelui.blogspot.com

27. RAZVAN CODRESCU

http://razvan-codrescu.blogspot.ro/

28.RADIO ARHIVE

https://www.facebook.com/RadioArhive/

29.IDEEA EUROPEANĂ

https://www.ideeaeuropeana.ro/colectie/opere-fundamentale/

30. SA NU UITAM

31. CERTITUDINEA

32. F.N.S.A

https://www.fnsa.ro/products/4546-dimitrie_cantemir_despre_numele_moldaviei.html

Evenimente

Anunturi

Această retea este pusă la dispoziţie sub Licenţa Atribuire-Necomercial-FărăModificări 3.0 România Creativ

Această retea este pusă la dispoziţie sub Licenţa Atribuire-Necomercial-FărăModificări 3.0 România Creativ

Parteneri

Note

Hoffman - Jurnalul cărților esențiale

1. Radu Sorescu - Petre Tutea. Viata si opera

2. Zaharia Stancu - Jocul cu moartea

3. Mihail Sebastian - Orasul cu salcimi

4. Ioan Slavici - Inchisorile mele

5. Gib Mihaescu - Donna Alba

6. Liviu Rebreanu - Ion

7. Cella Serghi - Pinza de paianjen

8. Zaharia Stancu - Descult

9. Henriette Yvonne Stahl - Intre zi si noapte

10.Mihail Sebastian - De doua mii de ani

11. George Calinescu Cartea nuntii

12. Cella Serghi Pe firul de paianjen…

Creat de altmariusclassic Dec 23, 2020 at 11:45am. Actualizat ultima dată de altmariusclassic Ian 24, 2021.

Top Members

© 2024 Created by altmarius.

Oferit de

![]()

Embleme | Raportare eroare | Termeni de utilizare a serviciilor

Pentru a putea adăuga comentarii trebuie să fii membru al altmarius !

Alătură-te reţelei altmarius